When Studio Ghibli announced that it would be ceasing production, it couldn’t help but feel like the end of an era. The studio which had made Japanese animation an internationally beloved art form was no more. Into the void stepped a brand new animation studio which vowed to pick up the Ghibli gauntlet – Studio Ponoc was formed by former Ghibli producer Yoshiaki Nishimura who enlisted a host of other ex-Ghibli talent including Arrietty director, Hiromasa Yonebayashi.

When Studio Ghibli announced that it would be ceasing production, it couldn’t help but feel like the end of an era. The studio which had made Japanese animation an internationally beloved art form was no more. Into the void stepped a brand new animation studio which vowed to pick up the Ghibli gauntlet – Studio Ponoc was formed by former Ghibli producer Yoshiaki Nishimura who enlisted a host of other ex-Ghibli talent including Arrietty director, Hiromasa Yonebayashi.

Mary and the Witch’s Flower (メアリと魔女の花, Mary to Majo no Hana), Ponoc’s first feature is, like Yonebayashi’s When Marnie was There, an adaptation of a classic British children’s novel. Part of the ‘70s children’s literature boom, Mary Stewart’s The Little Broomstick was more or less forgotten until the film, paradoxically, brought it back into print. Like many post-war children’s novels, The Little Broomstick is the story of a clever and kind little girl who thinks she doesn’t quite fit in. Mary and the Witch’s Flower is no different in this regard, even in updating the tale (seemingly) to the present day as its spiky heroine finds herself taking on mad scientists and crazed witches in a strange fantasy realm all while trying to get used to the comparatively gentle rhythms of country life.

Mary Smith (Hana Sugisaki) is bored. She hates her frizzy red hair which a horrible local boy, Peter (Ryunosuke Kamiki), uses as justification to describe her as a “red haired monkey”, and fears that the rest of her life will merely be a dull exercise in killing time until its inevitable conclusion. Mary has just moved in with her Great-Aunt Charlotte (Shinobu Otake) in the country while her parents are apparently working away and, as she still has a week left of summer holidays until school starts, she’s desperate for something to do. Unwisely following two cats into a misty forest, she chances upon a mysterious flower – the “Fly By Night” which blooms only once every seven years. With no respect for nature, Mary picks herself some of the pretty bulbs to take back to the gardener but unwittingly opens up a portal to another world. Taking hold of an abandoned broomstick, she finds herself swooped off to Endor College – an elite institution of witchcraft and wizardry where she dazzles all with her magical skills. Thinking she’s finally found her place, Mary is content to go along with everyone’s assumption that she is the new student they’ve been waiting for but on closer inspection, Endor College is not quite all it seems.

Mary’s initial dissatisfaction with herself is somewhat sidelined by the narrative but there’s something particularly poignant about her loathing of her red hair. In British culture at least, those with red hair often face a strange kind of “acceptable” prejudice, bullied and ostracised even into adulthood. Thus when Peter calls Mary a “red haired monkey” it isn’t cute or funny it’s just mean and she’s probably heard something similar every day of her life. When she rocks up at Endor and they tell her that her red hair makes her special and is the sign of high magic potential, it’s music to her ears but it’s also, perhaps, reinforcing the idea that simply having red hair makes her different from everyone else.

Feeling different from everyone else perhaps allows her to look a little deeper into the world of Endor than she might otherwise have done. Despite her conviction that she doesn’t fit in and is of no use to anyone, Mary is never seriously tempted by the promises of Endor which include untold power as well as a clear offer of acceptance and even respect. When she realises that the couple who run the school – a witch and a scientist, have been abusing their powers by committing heinous acts of experimentation on innocent “test subjects”, Mary learns to stand up for those who can’t stand up for themselves even if she couldn’t have done it for herself.

Messages about the seductive power of authoritarian regimes exploiting feelings of disconnection, the scant difference between magic and science, and the need for respect of scientific ethics in the pursuit of knowledge, all get somewhat lost amid Mary’s meandering adventures, as does Mary herself as her gradual progress towards realising that she possessed her own “magic” all along ticks away quietly in the background. Yet the biggest problem Mary and the Witch’s Flower faces is also its greatest strength – its ties to Studio Ghibli. With echoes of Yonebayashi’s previous adaptations of classic British literature, Mary and the Witch’s Flower also indulges in a number of obvious Ghibli homages from the Ponyo-esque flying fish and Laputa influenced design of Endor to the overt shot of Mary riding a deer on a rocky path, and the unavoidable girl+broomstick echoes of Kiki’s Delivery Service. Even if Mary and the Witch’s Flower cannot free itself from the burden of its legacy, it does perhaps fill the void it was intended to, if in unspectacular fashion.

Mary and the Witch’s Flower will be released in UK cinemas courtesy of Altitude Films in May 2018.

Original trailer (English subtitles)

Hiroya Oku’s long running manga series Gantz has already been adapted as a TV anime as well as two very successful live action films from Shinsuke Sato. Gantz:O (ガンツ:オー) is the first feature length animated treatment of the series and makes use of 3D CGI and motion capture for a hyperrealistic approach to alien killing action. “O” for Osaka rather than “0” for zero, the movie is inspired by the spin-off Osaka arc of the manga shifting the action south from the regular setting of central Tokyo.

Hiroya Oku’s long running manga series Gantz has already been adapted as a TV anime as well as two very successful live action films from Shinsuke Sato. Gantz:O (ガンツ:オー) is the first feature length animated treatment of the series and makes use of 3D CGI and motion capture for a hyperrealistic approach to alien killing action. “O” for Osaka rather than “0” for zero, the movie is inspired by the spin-off Osaka arc of the manga shifting the action south from the regular setting of central Tokyo.

History books make for the grimmest reading, subjective as they often are. Science fiction can rarely improve upon the already existing evidence of humanity’s dark side, but Genocidal Organ (

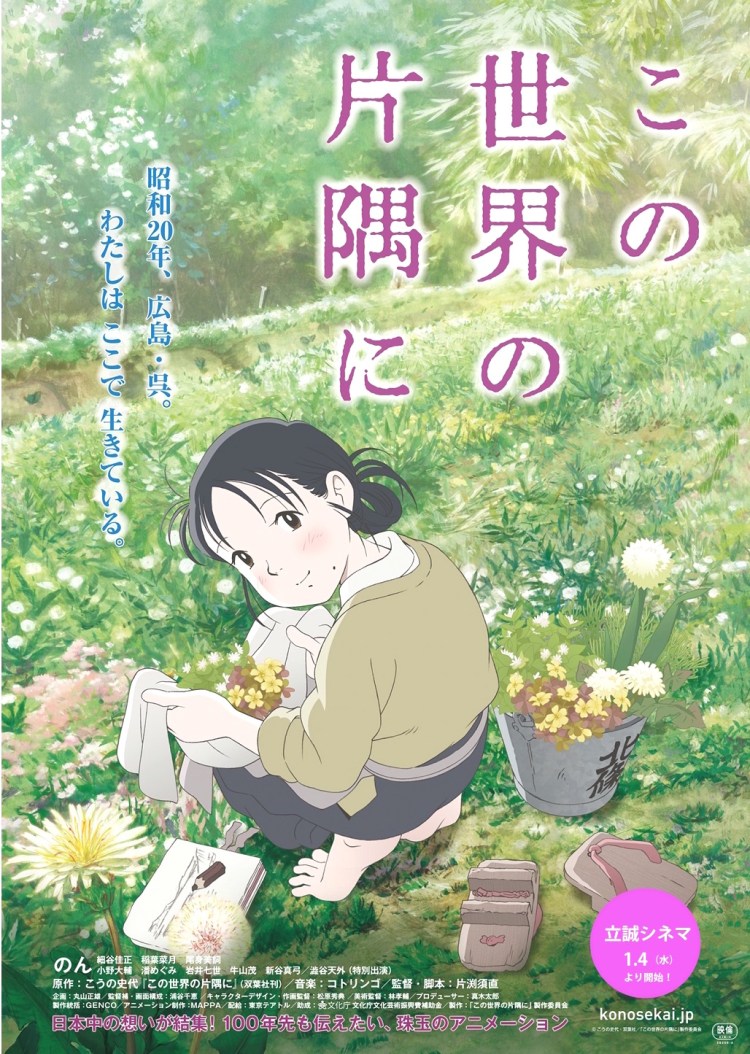

History books make for the grimmest reading, subjective as they often are. Science fiction can rarely improve upon the already existing evidence of humanity’s dark side, but Genocidal Organ ( Depictions of wartime and the privation of the immediate post-war period in Japanese cinema run the gamut from kind hearted people helping each other through straitened times, to tales of amorality and despair as black-marketeers and unscrupulous crooks take advantage of the vulnerable and the desperate. In This Corner of the World (この世界の片隅に, Kono Sekai no Katasumi ni), adapted from the manga by Hiroshima native Fumiyo Kouno, is very much of the former variety as its dreamy, fantasy-prone heroine is dragged into a very real nightmare with the frontier drawing ever closer and the threat of death from the skies ever more present but manages to preserve something of herself even in such difficult times.

Depictions of wartime and the privation of the immediate post-war period in Japanese cinema run the gamut from kind hearted people helping each other through straitened times, to tales of amorality and despair as black-marketeers and unscrupulous crooks take advantage of the vulnerable and the desperate. In This Corner of the World (この世界の片隅に, Kono Sekai no Katasumi ni), adapted from the manga by Hiroshima native Fumiyo Kouno, is very much of the former variety as its dreamy, fantasy-prone heroine is dragged into a very real nightmare with the frontier drawing ever closer and the threat of death from the skies ever more present but manages to preserve something of herself even in such difficult times.

Children – not always the most tolerant bunch. For every kind and innocent film in which youngsters band together to overcome their differences and head off on a grand world saving mission, there are a fair few in which all of the other kids gang up on the one who doesn’t quite fit in. Given Japan’s generally conformist outlook, this phenomenon is all the more pronounced and you only have to look back to the filmography of famously child friendly director Hiroshi Shimizu to discover a dozen tales of broken hearted children suddenly finding that their friends just won’t play with them anymore. Where A Silent Voice (聲の形, Koe no Katachi) differs is in its gentle acceptance that the bully is also a victim, capable of redemption but requiring both external and internal forgiveness.

Children – not always the most tolerant bunch. For every kind and innocent film in which youngsters band together to overcome their differences and head off on a grand world saving mission, there are a fair few in which all of the other kids gang up on the one who doesn’t quite fit in. Given Japan’s generally conformist outlook, this phenomenon is all the more pronounced and you only have to look back to the filmography of famously child friendly director Hiroshi Shimizu to discover a dozen tales of broken hearted children suddenly finding that their friends just won’t play with them anymore. Where A Silent Voice (聲の形, Koe no Katachi) differs is in its gentle acceptance that the bully is also a victim, capable of redemption but requiring both external and internal forgiveness.

Indie animation talent Makoto Shinkai has been making an impact with his beautifully drawn tales of heartbreaking, unresolvable romance for well over a decade and now with Your Name (君の名は, Kimi no Na wa) he’s finally hit the mainstream with an increased budget and distribution from major Japanese studio Toho. Noticeably more upbeat than his previous work, Your Name takes on the star-crossed lovers motif as two teenagers from different worlds come to know each other intimately without ever meeting only to find their youthful romance frustrated by the vagaries of time and fate.

Indie animation talent Makoto Shinkai has been making an impact with his beautifully drawn tales of heartbreaking, unresolvable romance for well over a decade and now with Your Name (君の名は, Kimi no Na wa) he’s finally hit the mainstream with an increased budget and distribution from major Japanese studio Toho. Noticeably more upbeat than his previous work, Your Name takes on the star-crossed lovers motif as two teenagers from different worlds come to know each other intimately without ever meeting only to find their youthful romance frustrated by the vagaries of time and fate.