Does it matter what path you take when none lead out of the darkness because all the world is dark? The heroine of Teinosuke Kinugasa’s Crossroads (十字路, Jujiro) eventually finds herself faced with this dilemma after a series of betrayals born of male failure place her into an impossible, infinitely ironic situation. Following his avant-garde masterpiece A Page Madness, Kinugasa heads in more straightforwardly melodramatic direction if maintaining the same expressionist aesthetic, but the world is still itself “mad” and inescapably so even as it prepares to swallow itself whole.

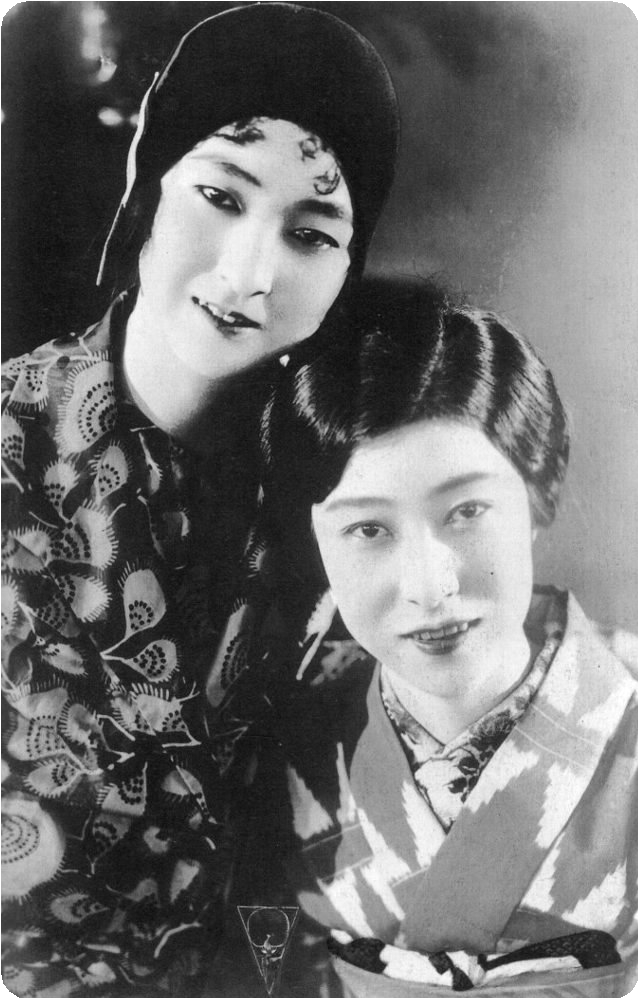

Okiku (Akiko Chihaya), an earnest young woman, lives in a small room on the second floor of a squalid tenement building, captured in all of its grotty detail by Kinugasa’s manically wandering yet claustrophobic camera, with her brother Rikiya (Junosuke Bando). She supports the pair of them through seamstressing and doing other odd jobs, while Rikiya has become a devotee of the red light district and developed an infatuation with Oume (Yukiko Ogawa), the proprietress of an archery parlour. So enamoured of her is he that he declares his intention to fight for her love, literally, and is badly beaten by a samurai rival. He steals the ornate kimono his sister had been preparing for a client and hands it to Oume only to reencounter the samurai who tears it in two and hits him on the head, throwing ashes into his eyes causing him to believe that he is blind. Rikiya embarrasses himself by crying out for a sign of love from Oume while clinging to another woman. Humiliated and unable to see, he bumps back into his rival and slashes at him with a sword. Someone shouts “murderer” and Rikiya stumbles out of the tavern and back to his sister believing he has killed someone while the samurai is in fact perfectly fine, merely having another joke at his expense.

The “joke” will have profound consequences, not only for Rikiya but for his devoted sister. Now entirely unsupported by her feckless brother and in fact burdened by him as he adjusts to his unsighted life, Okiku is determined to keep him safe from punishment for his legal transgression. This becomes another minor problem in their lives as a mysterious bogus policeman (Ippei Soma) with missing front teeth has begun hanging out in their front room for otherwise unexplained reasons, hinting that he knows all about Rikiya’s crime but offering to “protect” him from the authorities for the right price or a suitable alternative. Meanwhile, a doctor has also suggested that Rikiya’s eyes might be healed if he had money to heal them. An old hag having worn out a young woman she was exploiting for sex work is in search of a replacement and thinks Okiku fits the bill. She resists, but is at a loss as to how to find money both for the policeman and for her brother’s eyes.

Old hag aside, all of Okiku’s problems are born of male failure. Her feckless brother has drawn her into his foolish romantic fancy, allowing himself to be swept away sold on the false promises of the Yoshiwara. Questioned by another patron, Oume reveals that she liked Rikiya but is turned off by “persistent” men. She enjoys the attention she gets, not to mention the gifts, but is not interested in the kind of relationship which limits her freedom. The archery parlour itself is a carnivalesque world of giddy madness, a permanent party town filled with maniacal laughter and the false jollity of those trying to escape despair through mindless hedonism. Rikiya is blind to his delusion and has no idea he has been trapped. Unlike Oume, Okiku is a pure soul and unable to manipulate male interest for her own ends. She finds herself caught between the old hag and the bogus policeman trying to protect the brother who made no attempt to protect her, even hiding in a cupboard when he suspected that his attacker had followed him home.

Exploited from every possible angle, the siblings have nowhere left to turn but to each other. “If only I could live with you like this all my life” a chastened Rikiya exclaims, adding “I will take you, sister, wherever I escape” when the scene is ironically mirrored yet returning once again to Oume only to realise the degree to which he had been blinded by love even as he could see. Not even fraternal bonds are strong enough to survive the storm of human selfishness. Kinugasa conjures a world of spiralling madness in which cruelty and indifference are the only constants. It doesn’t matter which way you go, the destination is the same.

When one thinks of the classic examples of children in Japanese cinema, Hiroshi Shimizu is the name which comes to mind but family chronicler Yasujiro Ozu also made a few notable forays into the genre. I Was Born, But… (大人の見る絵本 生れてはみたけれど, Otona no miru ehon – Umarete wa mita keredo) stars one of the premier child actors of the silent era in Tokkan Kozo (later known as Tomio Aoki) who also worked repeatedly with Shimizu (

When one thinks of the classic examples of children in Japanese cinema, Hiroshi Shimizu is the name which comes to mind but family chronicler Yasujiro Ozu also made a few notable forays into the genre. I Was Born, But… (大人の見る絵本 生れてはみたけれど, Otona no miru ehon – Umarete wa mita keredo) stars one of the premier child actors of the silent era in Tokkan Kozo (later known as Tomio Aoki) who also worked repeatedly with Shimizu ( Hiroshi Shimizu is best remembered for his socially conscious, nuanced character pieces often featuring sympathetic portraits of childhood or the suffering of those who find themselves at the mercy of society’s various prejudices. Nevertheless, as a young director at Shochiku, he too had to cut his teeth on a number of program pictures and this two part novel adaptation is among his earliest. Set in a broadly upper middle class milieu, Seven Seas (七つの海, Nanatsu no Umi) is, perhaps, closer to his real life than many of his subsequent efforts but notably makes class itself a matter for discussion as its wealthy elites wield their privilege like a weapon.

Hiroshi Shimizu is best remembered for his socially conscious, nuanced character pieces often featuring sympathetic portraits of childhood or the suffering of those who find themselves at the mercy of society’s various prejudices. Nevertheless, as a young director at Shochiku, he too had to cut his teeth on a number of program pictures and this two part novel adaptation is among his earliest. Set in a broadly upper middle class milieu, Seven Seas (七つの海, Nanatsu no Umi) is, perhaps, closer to his real life than many of his subsequent efforts but notably makes class itself a matter for discussion as its wealthy elites wield their privilege like a weapon.

Like many other areas of the world in the first half of the 20th century, Japan also found itself at a dividing line of political thought with militarism on the rise from the late 1920s. Despite the onward march of right-wing ideology, the left was not necessarily silent. Ironically, the then voiceless cinema was able to speak for those who were its greatest consumers as an accidental genre was born detailing the everyday hardships faced by those at the bottom end of the ladder. These “proletarian films” or “tendency films” (keiko eiga) were increasingly suppressed as time went on yet, in contrast to the more politically overt cinema of the independent Proletarian Film League of Japan, continued to be produced by mainstream studios. Long thought lost, Shigeyoshi Suzuki’s What Made Her Do It? (何が彼女をそうさせたか, Nani ga Kanojo wo Sousaseta ka) was a major hit on its original release with some press reports even claiming the film provoked riots when audiences were passionately moved by the heroine’s tragic descent into madness and arson after suffering countless cruelties in an unfeeling world.

Like many other areas of the world in the first half of the 20th century, Japan also found itself at a dividing line of political thought with militarism on the rise from the late 1920s. Despite the onward march of right-wing ideology, the left was not necessarily silent. Ironically, the then voiceless cinema was able to speak for those who were its greatest consumers as an accidental genre was born detailing the everyday hardships faced by those at the bottom end of the ladder. These “proletarian films” or “tendency films” (keiko eiga) were increasingly suppressed as time went on yet, in contrast to the more politically overt cinema of the independent Proletarian Film League of Japan, continued to be produced by mainstream studios. Long thought lost, Shigeyoshi Suzuki’s What Made Her Do It? (何が彼女をそうさせたか, Nani ga Kanojo wo Sousaseta ka) was a major hit on its original release with some press reports even claiming the film provoked riots when audiences were passionately moved by the heroine’s tragic descent into madness and arson after suffering countless cruelties in an unfeeling world.