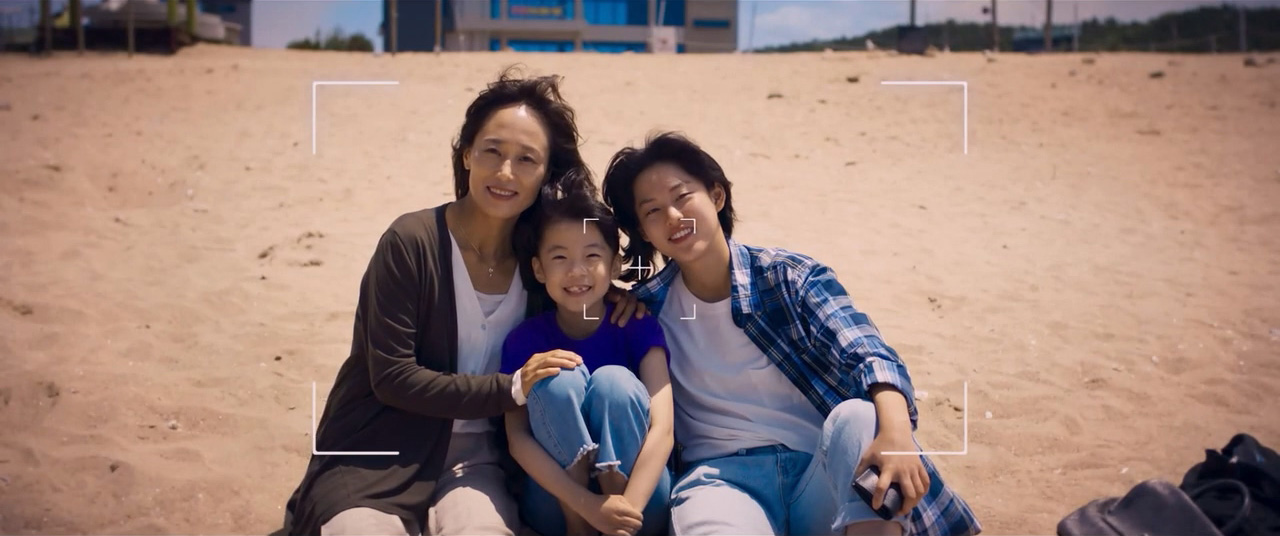

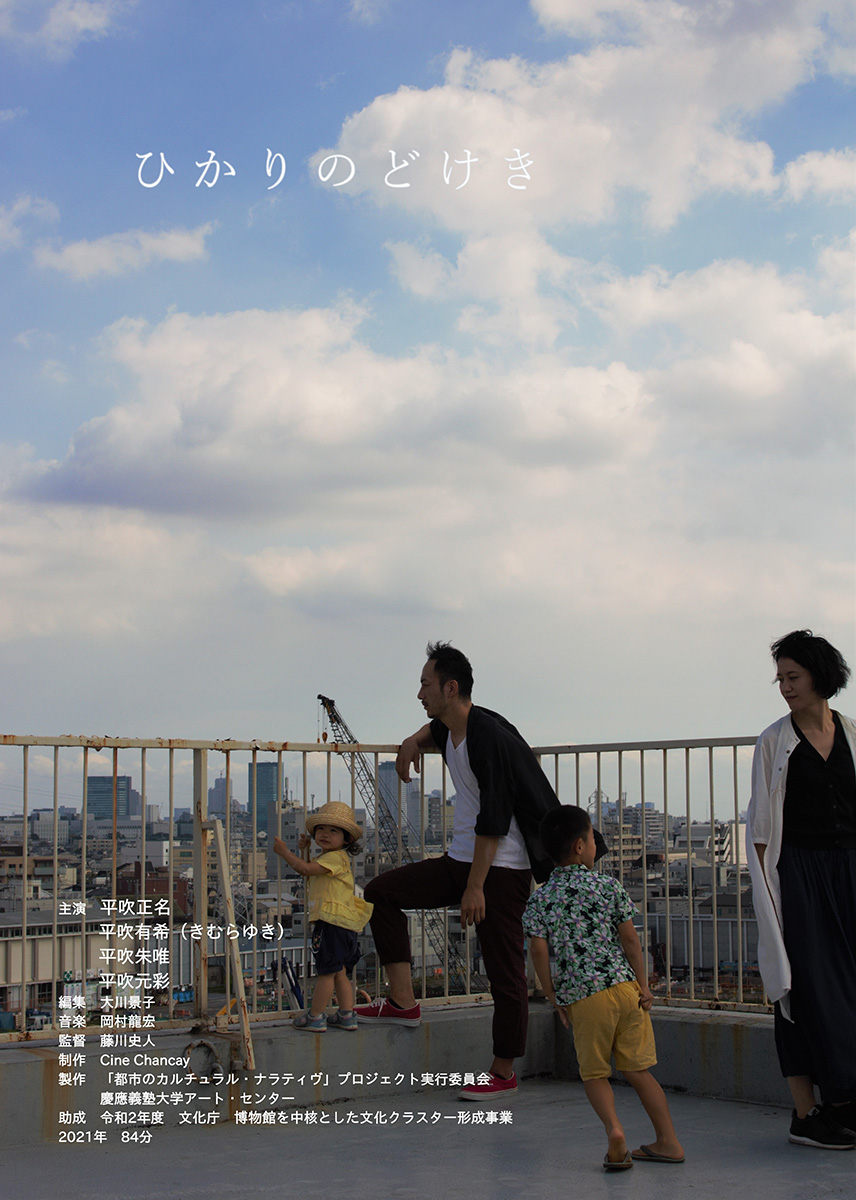

A shy young student of nuclear engineering’s horizons are broadened through her friendship with an eccentric old lady who runs a sex shop where she ends up working after being bamboozled into covering a classmate’s shifts in Janchivdorj Sengedorj’s charming coming-of-age dramedy The Sales Girl (Худалдагч охин, Khudaldagch ohin). Showing another side of contemporary Mongolia, Janchivdorj Sengedorj’s humorous tale turns on the unusual friendship that arises between the two women each in their own way lonely and looking for a kind of liberation from a sometimes hopeless existence.

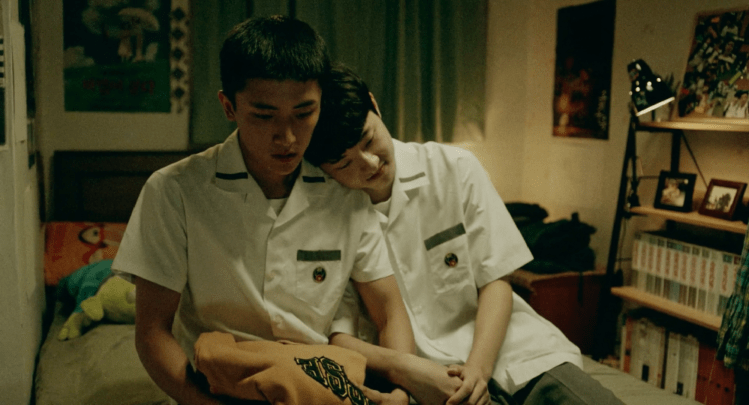

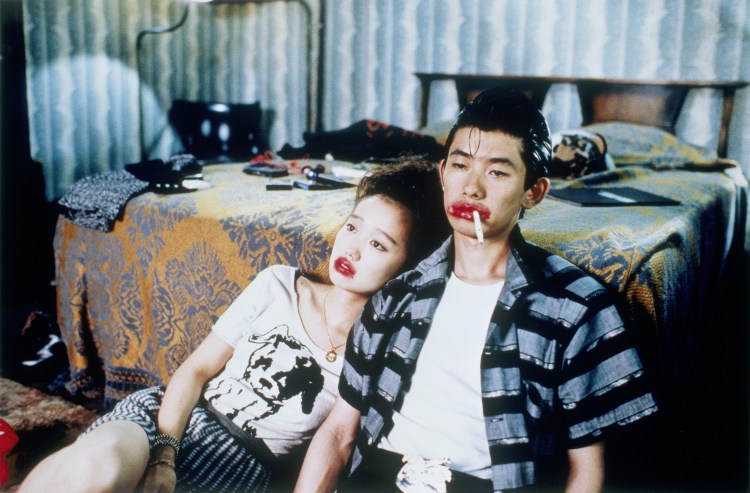

Saruul (Bayartsetseg Bayarjargal) is only studying nuclear engineering because her parents told her to and in truth would rather be an artist spending her evenings in her room crafting textured paintings rather than going out having fun. Her solitary air may be the reason she’s approached by another girl whom she hardly knows, Namuuna, who asks her to cover her shifts at work because she’s broken her leg slipping on a banana peel. Saruul is a little reluctant, unable to understand why Namuuna is being so secretive about the nature of her job anxious that she not tell anyone about where she works largely as we find out because it’s a sex shop run by an eccentric old lady whose cat she’s supposed to feed when she goes to drop off the day’s takings at her swanky new build townhouse. To begin with, Katya (Enkhtuul Oidovjamts) is gruff and unfriendly, somewhat unpleasant and intimidating yet something intrigues her about Saruul and gradually the two women begin to generate an awkward friendship.

As if immediately picking up on her inner conflict, Katya scoffs “where will that get you?” when Saruul explains she’s studying nuclear engineering perhaps fairly suggesting that in terms of finding steady income there may not be much difference between a career as a painter and someone with a degree in such a specific subject. In any case, Saruul is largely unfazed by the nature of her work at the sex shop, taking it mainly in her stride though telling her parents only that she’s been helping out with “deliveries” of “medications” including “human organs” which fits in nicely with Katya’s life philosophy in which she runs a “pharmacy” that sells things to help unhappy people find fulfilment and the self-confidence to restart their lives. Somewhat sceptical, Saruul tries out her advice on her friend’s dog Bim which she’d always thought seemed a bit bored and lethargic, “not really like a dog at all”, feeding him a tab of viagra and then panicking when he disappears only to discover him out living his best life running with the local strays.

Meanwhile under Katya’s influence she begins to open up too, getting a more fashionable haircut and dressing in a more individual fashion while embracing her sexuality in deciding to seduce her friend Tovdorj who is equally lost in contemporary Mongolian society where as he puts it you work all your life to get a small apartment and a Prius, planning to change his name to Jong-Su and become an actor only to be told he has “hollow, vapid eyes”. Saruul may be equally directionless but while fascinated by Katya’s sense of mystery, this elegant older woman with a Russian name who claims to have been a famous dancer but also at one point spent time in prison and now seems to be fabulously wealthy, she becomes disillusioned when presented with the dark sides of her work, almost arrested as a sex worker and then harassed by a creepy customer after unwisely agreeing to enter his home while attempting to deliver a package. As she points out, Katya is already quite divorced from “real life” and may struggle to understand the reality of Saruul’s existence living in a small apartment where her parents craft felt shoes to sell at the market after coming to the city when she was around 10 even though her father was once a teacher of Russian.

Then again as Saruul comes to realise Katya has had a lot of sadness in her life and the wisdom she has to impart is sound if often eccentric meditating on the fact that happiness that comes late is in its own way sad because you no longer have the capacity to enjoy it to its fullest. Even so, she is doing her best to chase happiness and helping others, Saruul included, to do the same. Gradually, Saruul sheds her ubiquitous headphones which allow her to zone out into an internal disco complete with flashing coloured lights to become more herself with a little help from her fairy godmother, the ever elusive Katya. Quirky yet heartfelt, The Sales Girl sheds new light on the concerns of young people in Mongolia but finally allows the reserved heroine to free herself of her preconceived notions to live her life the way she wants a little more aware of the world around her.

The Sales Girl screened as part of Osaka Asian Film Festival 2022

Original trailer (no subtitles)