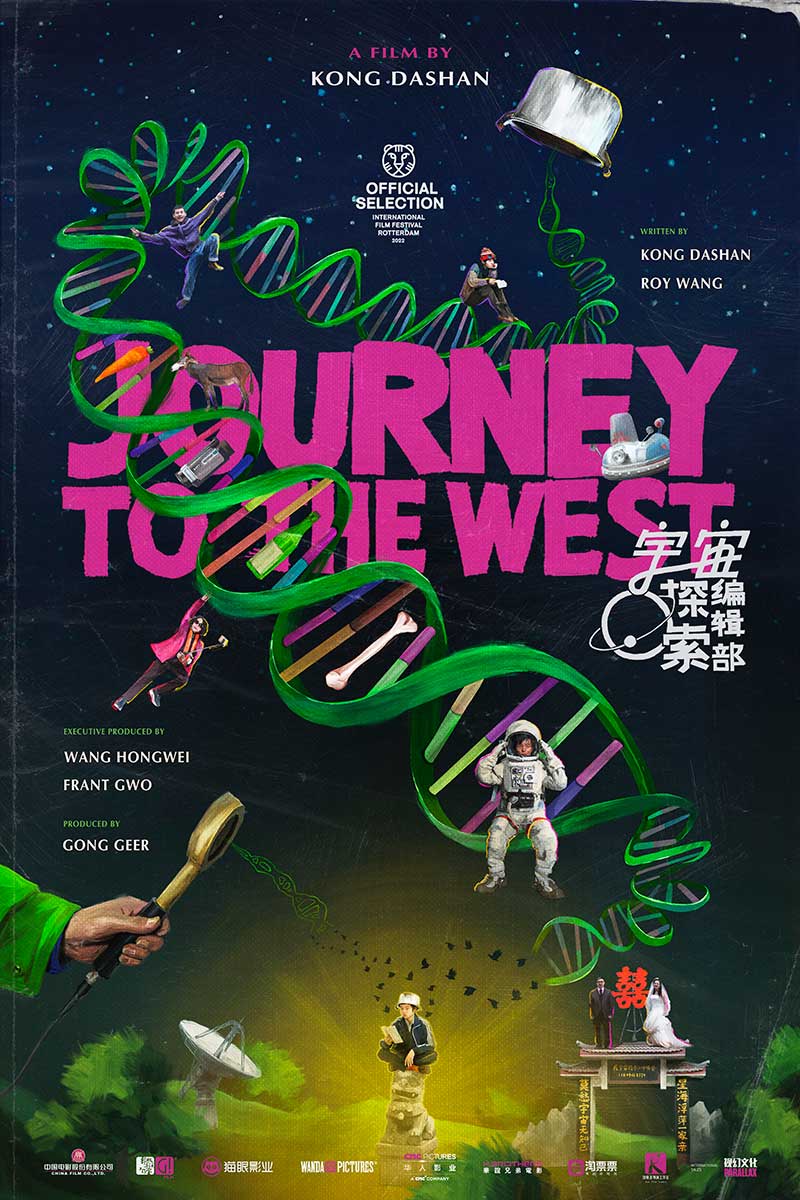

An eccentric middle-aged man’s search for alien contact sends him on a quest for enlightenment in Kong Dashan’s deadpan epic Journey to the West (宇宙探索编辑部, Yǔzhòu Tànsuǒ Biānjí Bù). Inspired by the classic Chinese tale of the monk Tang Sanzang who journeyed west in order to bring true Buddhism to China in the company of the anarchic monkey king Sun Wukong, Kong’s comical adventure finds its awkward hero longing for connection in contemporary China his search for the extraterrestrial a means of provoking the next great human evolution in the belief that on the discovery of alien life humanity would immediately abandon its petty disagreements and live in perpetual harmony.

Kong opens however with some VHS footage from 1990 in which UFO-obsessive Tang (Yang Haoyu) is interviewed for a documentary before flashing forward 30 years to the present day in which Tang has made little progress. The magazine which he edits, Universe Exploration, is on the brink of bankruptcy with his exasperated boss Mrs Qin (Ai Liya) already holding tours for prospective sponsors none of which go particularly well. As we later discover, Tang’s obsession has dominated his life resulting in the breakdown of his marriage while his daughter later died by her own hand it seems in part because of the same despair he too feels in his inability to understand the purpose of human existence. His quest is partly one for answers, though his theories often sound unhinged as he patiently explains about messages in the white snow of a detuned analogue television or pays visits to psychiatric institutions believing that psychopaths whose brains are wired differently may be better able to receive extraterrestrial signals.

On the other hand, his way of life is not perhaps that different to that of his namesake Tang Sanzang in his wilful aestheticism insisting that the desire for better food along with sex for reasons other than procreation is merely a consumerist trap actively blocking the path towards human evolution which he believes he will discover in contacting extraterrestrial life. In his theory, if the Earth is like a grain of sand in the desert of the universe then it’s illogical to assume there are not other beings out there whom he assumes will be far advanced not only in technological terms but also in morality. But then, as a poet he later meets on his journey west into the mountains eventually asks him what if the aliens don’t have any answers either and have in fact come to Earth in order to ask the exact same question for which Tang seeks the solution?

Inevitably, the conclusion that he comes to is that the answer lies within, that humanity is the universe and each person a single word in a great poem centuries in the making that might in its conclusion allow us to understand why we live if only we can go on connecting with each other to form new sentences in the great unfinished journey towards enlightenment. Then again, Mrs Qin hints at the mean spiritedness of the contemporary society in her conviction that if there are aliens out there who want to come to Earth it’s probably to rob it, while out on the road Tang is taken in by a bizarre scam involving the body of an alien in a freezer you can only see if you are the chosen one which requires the willingness to pay $99.99 to man running the alien embassy on Earth though it does at least result in Tang receiving a mysterious bone which does seem to be crucial to his quest once he runs into monkey king stand in Sun Tiyong (Wang Yitong) who wears a saucepan on his head and claims to have received a mission to retrieve a stone ball stolen from a lion statue’s mouth from a mysterious alien entity.

Ever mindful of the contemporary realities, Kong throws in several ironic nods to the censors board Tang repeatedly reminded that he must always find a “scientific” explanation for bizarre phenomena rather than succumbing to “superstition”. Travelling west with Sun and a small team including his drunken friend and a young woman the same age as his daughter would have been if she’d lived, Tang does indeed undergo a kind of vision quest culminating in the apotheosis of Sun into Wukong while a strange man in a red hat riding a tiny UFO-like cart always seems to be one step ahead of them. Shot in a faux documentary style complete with direct to camera interviews and occasional breaking of the fourth wall, Kong’s hilariously deadpan, absurdist epic sees Tang journeying west in search of the meaning of life only to be confronted by the vastness of the universe and discover himself, and the answer he seeks, already in its embrace.

Journey to the West screened as part of Osaka Asian Film Festival 2022

Clip (English subtitles)