In less enlightened times, unplanned teenage pregnancy was sometimes seen as a grand tragedy involving the potential ruin of at least three lives. Thankfully, in many places at least, it isn’t quite like that anymore though for the young couple at the centre of Gina S. Noer’s sensitive yet lighthearted drama Two Blue Stripes (Dua Garis Biru) their impending parenthood exposes a series of divisions in a changing society as their families, one poor and religious, the other wealthy and secular though obsessed with respectability, react in quite different ways to the news their child is about to have a child of their own.

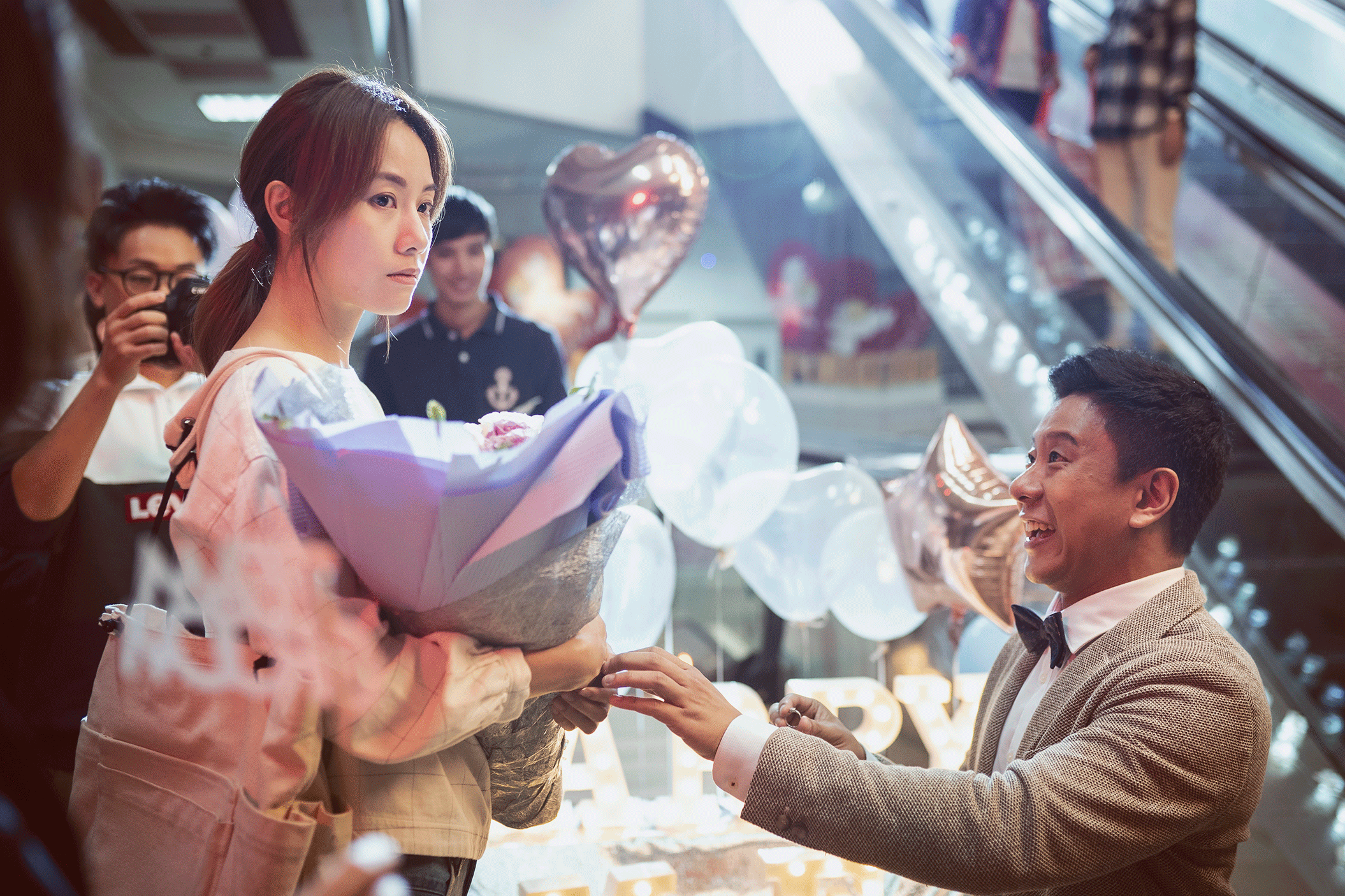

At 17, Bima (Angga Yunanda) and Dara (Adhisty Zara) are a bashful high school couple eagerly planning their futures. While Bima is not exactly a top student, Dara gets good grades and is obsessed with K-Pop, hoping to travel to Korea for university. One day however they get a little carried away and some time later Dara begins to suspect she may be expecting. Originally opting for an abortion, she later finds she can’t go through with it and the young couple decide that if only they can keep the pregnancy a secret until after graduation they’ll be able to figure something out. Unfortunately, however, the ruse is uncovered when Dara is taken ill during a PE session and accidentally reveals the pregnancy while worried about the baby.

The surprising thing is that Bima’s parents who are devoted to their Islamic faith are the most sympathetic, quickly accepting that what’s happened has happened and needs to be dealt with as calmly and sensitively as possible if also somehow disappointed in Bima while quietly proud of his surefooted though naive pledge to take responsibility. Dara’s parents, however, and in particular her mother Rika (Lulu Tobing) are far less understanding, intensely questioning their daughter in the grim “hope” that Bima may have forced himself on her and she is therefore “blameless”. This rather old fashioned, sexist notion of female purity is further borne out by the school who confess that they aren’t allowed to expel Dara because of her pregnancy, but all the same are asking her to leave meaning she won’t be able to take her exams with the other pupils while nothing will happen to Bima who will be permitted to go to class as normal.

For Rika shame and confusion seem to be the primary motivators. Attempting to sweep the whole thing under the carpet, she begins talking to a pair of relatives who are desperate for a baby and weren’t able to have any of their own in the hope they will adopt. Affluent and seemingly secular, her worry is perhaps only partly reputation and the fear her own parenting will be called in question with the remainder a sense of frustration that a single moment may have undone all her daughter’s hopes for the future along with all the ambitions she had for her.

Dara, meanwhile, continues to dream of going to Korea hoping somehow she’ll be able to make it work as young mother. For his part, Bima makes it clear that she should be able to fulfil her dreams if that’s what she wants, never trying to tie her down and always keen to shoulder his sense of the burden. Young and in love they want to stay together and try to make a family of their own, but they are also naive little realising both the differences between them and difficulties of supporting themselves independently. Bima ends up working in his father-in-law David’s (Dwi Sasono) restaurant, proving a good employee and perhaps earning his respect but simultaneously losing Dara’s as he slacks off on his studies, she somewhat disappointed to think he might end up waiting tables for the rest of his life exposing her slightly snobbish attitude further borne out by her reaction on arriving at Bima’s comparatively humble family home.

In an interesting role reversal, however, it is eventually Bima who takes on the stereotypically “maternal” role pledging to stay home and raise his son while affording Dara the opportunity to pursue her dreams. The parents meanwhile also reflect on their failure to properly prepare their children for adulthood, wishing that they had been less bashful and talked properly about sex so that they might have made better informed choices. “How are we supposed to love, to breathe, to be, when it hurts?” asks the plaintive song running over the closing scenes ironically titled “Growing Up”, each of the youngsters perhaps wondering just that as they try to come to terms with their respective choices while embarking on the next stage of their lives no longer children but perhaps no more certain.

Two Blue Stripes streams in the US until March 31 as part of the 12th season of Asian Pop-Up Cinema.

Original trailer (English subtitles)