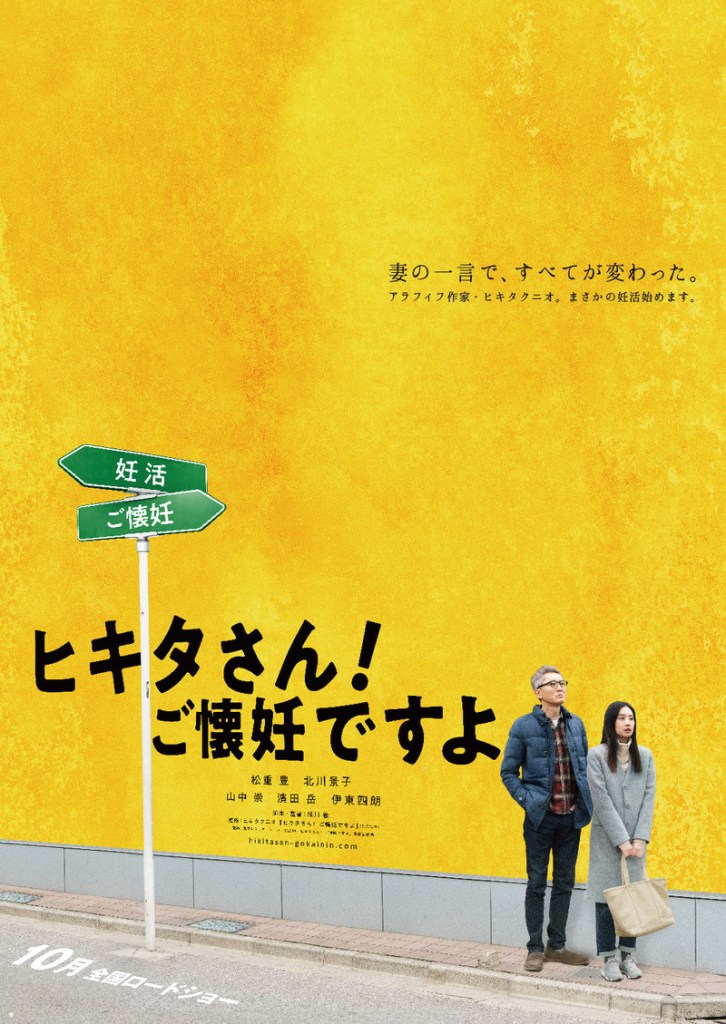

Even once you’ve entered a comfortable middle age in which you assume everything will remain pretty much the same until the day you die, life can still surprise you. So it is for the hero of Toru Hosokawa’s The Hikita’s are Expecting (ヒキタさん! ご懐妊ですよ, Hikita-san! Gokainin Desu yo), inspired by writer Kunio Hikita’s autobiographical essay in which he humorously recounts his experiences of undergoing fertility treatment with his considerably younger wife, a process which of course places an immense strain on their relationship but also brings them together as they remain determined to meet their baby by any means possible.

At 49, however, Kunio (Yutaka Matsushige) is a typical middle-aged man, set in his ways and fond of a drink. He and his younger wife Sachiko (Keiko Kitagawa) had made a mutual decision not to have children, but as many of her friends become mothers Sachiko begins to change her mind, especially after she witnesses Kunio help to calm a little boy having a tantrum at the bus stop. Kunio had been fairly indifferent to the idea of children and is in any case a passive personality so has no real objection only pausing to process the fact that his life might be about to change. He is not anticipating any problems and assumes conceiving a child will be a fairly straightforward process but after months of trying the natural way they start to wonder if something might be wrong. Kunio had not been expecting to discover that the problem lies with him. His sperm has low mobility, and it is unlikely Sachiko will become pregnant without medical help.

This news is something of a blow to Kunio’s sense of masculinity, especially in comparison to his editor (Gaku Hamada) who has several children already and keeps getting his wife pregnant by accident even while actively trying not to. Kunio doesn’t want to think that he’s at fault and pins his hopes on there being some kind of mistake but is forced to face the fact that though it’s just one of those things he will not be able to fulfil Sachiko’s desire to have a child all on his own. Nevertheless, he becomes determined to do everything he can to help, embracing a few old wives tales like putting a picture of a pomegranate on your wall and obsessively eating peaches while taking steps to lead a healthier lifestyle such as abstaining from alcohol and going on regular runs.

He’s also challenged however by Sachiko’s conservative and extremely authoritarian father who has never approved of the marriage for a number of reasons ranging from the age difference to Kunio’s liberal outlook and way of life. It’s no surprise that he doesn’t approve of their decision to have children, but his branding of fertility treatment as “disgraceful” is at best insensitive and his attempt to order his daughter to to “reconsider”, blaming all the problems on Kunio and advising that she leave him to find someone her own age he assumes would be more fertile, extremely inappropriate. Perhaps still a little gaslit, Sachiko finds herself unable to stand up him, even while Kunio points out that whatever their decision it’s entirely between them as husband and wife and he’s not even really sure why they’re having this bizarre family conference in the first place.

Meanwhile, they find themselves tested by the strain of undergoing fertility treatment. To begin with, Kunio foregrounds his own embarrassment and inconvenience, complaining about being made to wait in the fertility clinic while a host of heavily pregnant women put up with their discomfort in silence while sitting right next to him, but later feels guilty that it’s Sachiko who has to endure a number of supposedly painless surgical procedures on his account even though there’s nothing medically wrong with her. Together they experience joys and setbacks, occasionally overcome with despair, but always supporting each other and moving forward with good humour determined to become parents no matter what it takes. At the clinic, Kunio gets talking to another man who seems depressed and exhausted, explaining that they’ve been trying for six years and have decided to call it quits if this last treatment ends without success. Some time later he spots the man and his wife in the street, alone, but whatever the outcome was apparently much happier and rejoicing in each other’s company. Kunio at least is reassured, supporting his wife as they work together to expand their family, knowing that whatever happens at least they have each other.

The Hikita’s Are Expecting! streams for free in the US on June 19 as part of Asian Pop-Up Cinema’s Father’s Day Cheer mini series. Sign up to receive the viewing link (limited to 300 views) and activate it between 2pm and 10pm CDT after which you’ll have 24 hours to complete watching the movie.

Original trailer (English subtitles)