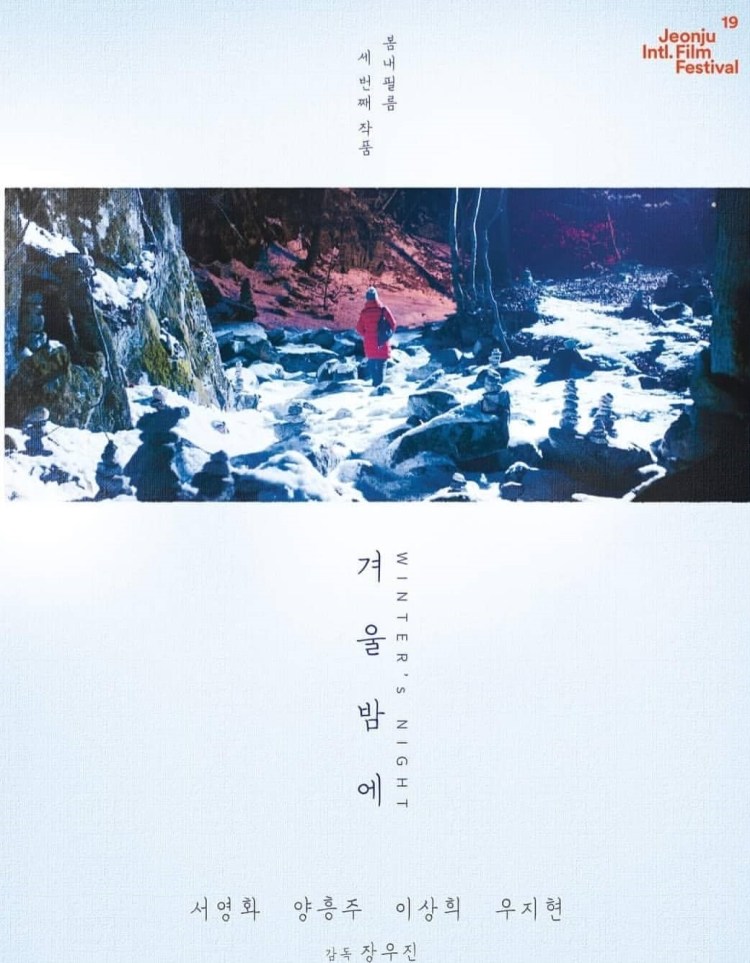

“You clumsy man, don’t lose her again!” a busybody landlady instructs the hero of Jang Woo-jin’s Winter’s Night (겨울밤에, gyeoulbam-e), neatly cutting to the heart of the matter with just a few well directed words. In Korean cinema, the is past always painfully present but our pair of dejected lovers haunt themselves with echoes of lost love and pangs of regret mixed with a hollow fondness for the days of youth. The fire has long since died, but the memory of its warmth refuses to fade.

“You clumsy man, don’t lose her again!” a busybody landlady instructs the hero of Jang Woo-jin’s Winter’s Night (겨울밤에, gyeoulbam-e), neatly cutting to the heart of the matter with just a few well directed words. In Korean cinema, the is past always painfully present but our pair of dejected lovers haunt themselves with echoes of lost love and pangs of regret mixed with a hollow fondness for the days of youth. The fire has long since died, but the memory of its warmth refuses to fade.

We first meet Eun-ju (Seo Young-hwa) and her husband Heung-ju (Yang Heung-joo) in a taxi driven by an extremely chatty man of about the same age which is to say around 50. Heung-ju, sitting uncomfortably in the front while his wife sits alone in the back, explains that he first came to this area 30 years previously when he did his military service. Bored and perhaps irritated by her husband’s conversation, Eun-ju realises she has lost her phone and insists they turn back to go and look for it at the temple they have just left. Heung-ju is annoyed but makes a show of humouring his wife while she refuses to leave, forcing the couple to stay overnight in a small inn that he later realises is the same place they stayed 30 years ago on the very night that they first became a couple.

As is pointed out to Eun-ju several times, losing a phone is an inconvenient and expensive mistake but perhaps not the end of the world. Nevertheless she continues to hunt for it as if it were her very soul, eventually explaining to a confused monk that it is all she has and even if she were to buy another one it wouldn’t be the same. Eun-ju’s attachment to her phone may hint at a deeper level of loss which has contributed to the distance she feels between herself and her husband, but the search is as much metaphorical as it is literal, sending both husband and wife out on a quest to look for themselves amid the icy caves and snow covered bridges.

An early attempt to check CCTV yields a pregnant image of a young soldier (Woo Ji-hyun) and a girl (Lee Sang-hee) sitting across from each other before they disappear and are replaced by the older Eun-ju and Heung-ju. Eun-ju later re-encounters the younger couple several times, becoming witness to their impossibly innocent romance which is such an eerie reminder of her own that one wonders if they are simply ghosts of her far off past. The soldier, an earnest, shy poet tries and fails to stop the girl walking onto the same thin ice that Eun-ju will later brave not quite so successfully, while the girl gleefully tells him that she has recently broken up with her boyfriend. They are young and filled with hope for the future, while Eun-ju is older and filled only with disappointment. Still, there is something in her that loves these young not-yet-lovers for all the goodness that is in them as she takes the younger woman, and her younger self, in her arms and warmly reassures her that the future is not so bleak as it might one day seem.

Meanwhile, a petulant Heung-ju has gone out looking for his “lost” wife but been distracted by the shadow of another woman (Kim Sun-young) wandering across the back of his mind. He drinks too much and ends up singing sad solo karaoke before discovering an old flame sleeping on a hidden sofa. She doesn’t immediately recognise Heung-ju and so runs away in fear, but later joins him for a drink over which she flirts raucously but probably not seriously while he moons over his wife, mourns an old friend, and recalls their student days lived against the fiery backdrop of the democracy movement.

Together again the couple attempt to talk through their mutual heartaches, expressing a mild resentment at the other’s unhappiness and their own inability to repair it, but seem incapable of bridging the widening gulf which has emerged between them. Trapped in an endless loop of romantic melancholy, the pair fail to escape the wintery temple where, it seems, a part of them will always remain, haunting the desolate landscape with the absence of recently felt warmth. A beautifully pitched exploration of middle-aged malaise and the gradual disillusionment of living, Winter’s Night tempers its vision of unanswerable longing with quiet hope as its two dejected lovers hold fast to the desire to begin again no matter how futile it may turn out to be.

Winter’s Night was screened as the first teaser for the 2019 London Korean Film Festival. Tickets for the next teaser screening, Default at Regent Street Cinema on 20th May, are already on sale.

Original trailer (English subtitles)