In the world of the Hong Kong action flick, the bad guys are often the good guys, and the “good guys” not so good after all. Even crooks have their code and there are rules which cannot be broken ensuring the heroes, even when they’re forced into morally dubious acts, emerge with a degree of nobility in having made a free choice to preserve their honour over their life. In Mainland China, however, things are a little different. The bad guys have to be thoroughly bad and the good guys squeaky clean. You won’t find any dodgy cops or dashing villains in a thriller from the PRC where crime can never, ever, pay. And then, enter Johnnie To who manages to exactly what the censors board asks of him while at the same painting law and chaos as two sides of the same coin, each deluded and obsessed, engaged in an internecine war in which the idea of public safety has been all but forgotten.

In the world of the Hong Kong action flick, the bad guys are often the good guys, and the “good guys” not so good after all. Even crooks have their code and there are rules which cannot be broken ensuring the heroes, even when they’re forced into morally dubious acts, emerge with a degree of nobility in having made a free choice to preserve their honour over their life. In Mainland China, however, things are a little different. The bad guys have to be thoroughly bad and the good guys squeaky clean. You won’t find any dodgy cops or dashing villains in a thriller from the PRC where crime can never, ever, pay. And then, enter Johnnie To who manages to exactly what the censors board asks of him while at the same painting law and chaos as two sides of the same coin, each deluded and obsessed, engaged in an internecine war in which the idea of public safety has been all but forgotten.

The film begins with the conclusion of an undercover operation run by Captain Zhang (Sun Honglei) in which he successfully disrupts a large scale smuggling operation. Meanwhile, meth cook Timmy Choi (Louis Koo) attempts to escape after an explosion kills his wife and her brothers but drives directly into a restaurant and is picked up by the police. Timmy soon wakes up and tries to escape but is eventually recaptured – from inside the chiller cabinet in the morgue in a particularly grim slice of poetic irony. Seeing as drug manufacture carries the death penalty in the PRC, Timmy turns on the charm. He’ll talk, say anything he needs to say, to save his own life. Including giving up his buddies.

Timmy is, however, a cypher. His true intentions are never quite clear – is he really just an opportunist doing whatever it takes to survive, or does he still think he can escape and is engaged in a series of clever schemes designed outsmart the ice cool Zhang? Zhang takes the bait. Eyeing a bigger prize, he lets Timmy take him into the heart of a finely tuned operation even playing the part of loudmouth gangster Haha in a studied performance which reinforces the blankness of his officialdom. Zhang is certain he is in control. He is the law, he is the state, he is the good.

Could he have misread Timmy? Zhang doesn’t think so. Timmy remains calm, watchful. Eventually he leads Zhang to a bigger drug factory staffed by a pair of mute brothers who have immense respect for their boss. Suddenly Timmy’s impassive facade begins to crack as he tells his guys about his wife’s passing but it’s impossible to know if his momentary distress is genuine, a result of mounting adrenaline, or simply part of his plan – he does, after all, need to get the brothers to give themselves away. Unbeknownst to Timmy, however, the brothers are pretty smart and might even be playing their own game.

To pits Hong Konger Timmy against Captain Zhang of the PRC in a game of cat and mouse fuelled by conflicting loyalties and mutual doubts. Whatever he’s up to, Timmy is a no good weasel who is either selling out his guys or merely pretending to so that he can save them (or maybe just save himself and what’s left of his business). Zhang, meanwhile, is a singleminded “justice” machine who absolutely will not stop, ever, until all the drug dealers in China have been eradicated. Yet isn’t all of this destruction a little bit much? Zhang doesn’t really care about the drugs because drug abuse wrecks people’s lives, maybe he doesn’t really care about the law but only about order and control, and what men like Timmy represent is a dangerous anarchy which exists in direct opposition to his conception of the way the world ought to work.

There is a degree of subversive implication in the seemingly overwhelming power of the PRC coupled with its uncompromising rigidity which paradoxically makes it appear weak rather than strong, desperate to maintain an image of control if not the control itself. The final fight takes place in front of a school with a couple of completely non-fazed and very cute little children trapped inside a school bus – Timmy does at least try to keep them calm even while using them as part of his plan, but Zhang and his guys seem to care little for the direction of the stray bullets they are spraying in order to win the internecine battle with the drug dealers and stop Timmy in his tracks once and for all. A pared down, non-stop action juggernaut, Drug War (毒戰, Dú Zhàn) is another beautifully constructed, infinitely wry action farce from To which takes its rather grim sense of humour all the way to the tragically ironic conclusion.

International trailer (English subtitles)

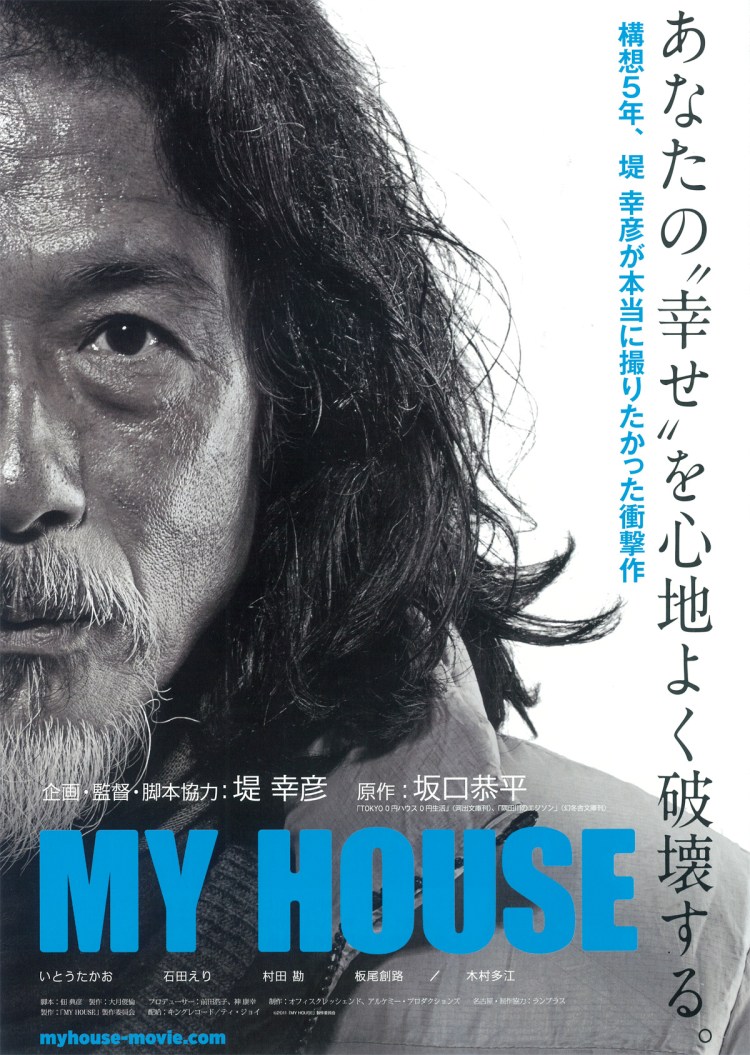

Yukihiko Tsutsumi has made some of the most popular films at the Japanese box office yet his name might not be one that’s instantly familiar to filmgoers. Tsutsumi has become a top level creator of mainstream blockbusters, often inspired by established franchises such as TV drama or manga. Skilled in many genres from the epic sci-fi of Twentieth Century Boys to the mysterious comedy of Trick and the action of SPEC, Tsutsumi’s consumate abilities have taken on an anonymous quality as the franchise takes centre stage which makes this indie leaning black and white exploration of the lives of a group of homeless people in Nagoya all the more surprising.

Yukihiko Tsutsumi has made some of the most popular films at the Japanese box office yet his name might not be one that’s instantly familiar to filmgoers. Tsutsumi has become a top level creator of mainstream blockbusters, often inspired by established franchises such as TV drama or manga. Skilled in many genres from the epic sci-fi of Twentieth Century Boys to the mysterious comedy of Trick and the action of SPEC, Tsutsumi’s consumate abilities have taken on an anonymous quality as the franchise takes centre stage which makes this indie leaning black and white exploration of the lives of a group of homeless people in Nagoya all the more surprising. If

If  Waking up in a strange place with absolutely no recollection of how you got there is bad enough. Waking up next to a total stranger is another degree of awkward. Waking up not in someone else’s apartment but in a department store furniture showroom is another kind of problem entirely (let’s hope the CCTV cameras were on the blink, eh?). This improbable situation is exactly what has befallen two lonely Beijinger’s in Derek Tsang and Jimmy Wan’s elegantly constructed romantic comedy meets procedural, Lacuna (醉后一夜, Zuì Hòu Yīyè). An extreme number of unexpected events is required to bring these two perfectly matched souls together, but the love gods were smiling on this particular night and, once the booze has worn off, romance looks set to bloom .

Waking up in a strange place with absolutely no recollection of how you got there is bad enough. Waking up next to a total stranger is another degree of awkward. Waking up not in someone else’s apartment but in a department store furniture showroom is another kind of problem entirely (let’s hope the CCTV cameras were on the blink, eh?). This improbable situation is exactly what has befallen two lonely Beijinger’s in Derek Tsang and Jimmy Wan’s elegantly constructed romantic comedy meets procedural, Lacuna (醉后一夜, Zuì Hòu Yīyè). An extreme number of unexpected events is required to bring these two perfectly matched souls together, but the love gods were smiling on this particular night and, once the booze has worn off, romance looks set to bloom . You can become the King of all Korea and your mum still won’t be happy. So it is for poor Prince Sungwon (Kim Dong-wook) who becomes accidental Iago in this Joseon tale of betrayal, cruelty, and love turning to hate in the toxic environment of the imperial court – Kim Dae-seung’s The Concubine (후궁: 제왕의 첩, Hugoong: Jewangui Chub). Power and impotence corrupt equally as the battlefield shifts to the bedroom and sex becomes weapon and currency in a complex political struggle.

You can become the King of all Korea and your mum still won’t be happy. So it is for poor Prince Sungwon (Kim Dong-wook) who becomes accidental Iago in this Joseon tale of betrayal, cruelty, and love turning to hate in the toxic environment of the imperial court – Kim Dae-seung’s The Concubine (후궁: 제왕의 첩, Hugoong: Jewangui Chub). Power and impotence corrupt equally as the battlefield shifts to the bedroom and sex becomes weapon and currency in a complex political struggle. Stories of old men trying to recapture their lost youth through projecting their fantasies onto pretty young women are not exactly rare and the protagonist of Jung Ji-woo’s Eungyo ( AKA A Muse, 은교) is just as aware as most that his dreams of youthful romance border on the ridiculous. A tale of loss, nostalgia, and jealousy both professional and personal, Eungyo is a poetic exploration of the burdens and benefits of age which are often invisible to those who can only look forwards.

Stories of old men trying to recapture their lost youth through projecting their fantasies onto pretty young women are not exactly rare and the protagonist of Jung Ji-woo’s Eungyo ( AKA A Muse, 은교) is just as aware as most that his dreams of youthful romance border on the ridiculous. A tale of loss, nostalgia, and jealousy both professional and personal, Eungyo is a poetic exploration of the burdens and benefits of age which are often invisible to those who can only look forwards.