The “hahamono” or mother movie has gone out fashion in recent years. Yoji Yamada’s World War II melodrama Kabei or Keisuke Yoshida’s more contemplative examination of modern motherhood My Little Sweet Pea might be the best recent examples of this classic genre which arguably reached its golden age in the immediate post-war period with its tales of self-sacrificing mothers willing to do whatever it took to ensure the survival or prosperity of their often cold or ungrateful children. After “Capturing Dad” Ryota Nakano turns his attention to mum, or more precisely the nature of motherhood itself in a drama about family if not quite a “family drama” as a recently single mother is busy contending with financial hardship and a sullen teenage daughter when she’s suddenly caught off guard by a stage four cancer diagnosis.

Futaba (Rie Miyazawa) is an outwardly cheerful woman, the sort who’s always putting a brave face on things and faces her challenges head on, proactively and without the fear of failure. Her husband, Kazuhiro (Joe Odagiri), ran off a year ago and no one’s heard from him since. Having closed the family bathhouse Futaba works part-time at a local bakery and cares for her daughter Azumi (Hana Sugisaki) alone but when she collapses at work one day Futaba is forced to confront all those tell signs that something’s wrong she’s been too busy to pay attention to. Inevitably it’s already too late. Futaba has stage four cancer and there’s nothing to be done but Futaba is Futaba and so she has things to do while there’s still time.

Some people colour the air around them, instantly knowing how to make the world a better place for others if not quite for themselves, except by extension. Futaba is one such person – the personification of idealised maternity whose instinctual, altruistic talent for love and kindness knows no bounds or boundaries. Yet at times her love can be a necessarily tough one as she negotiates the difficult process of trying to get her shy teenage daughter to stand up to the vicious group of bullies who’ve been making her school life a misery. Faced with an accelerated timeframe, Futaba needs to teach her little girl to be an independent woman a little ahead of schedule, knowing that she won’t be around to offer the kind of love and support she’ll be needing during those difficult years of adolescence.

Not wanting to leave her entirely alone, Futaba tracks down Kazuhiro only to find he’s now the sole carer for the nine-year old daughter of the woman he left her for who may or may not be his. Futaba decides to take the pair of them in but little Ayuko is just as sullen and distanced as her older half-sister as she struggles with ambivalent emotions towards the mother who abandoned her with a “father” she hardly knew. Futaba’s big idea is to reopen the family bathhouse to be run as a family where everyone has their place and personal responsibility, working together towards a common goal and supporting each other as they inevitably grow closer.

Unlike the majority of hahamono mothers, Futaba’s love is truly boundless as she tries not only to provide for her own children but for all the neglected, lonely, and abandoned people of the world. Bonding with the little girl of the private investigator she hires to find Kazuhiko, trying to comfort Ayuko as she deals with the fact that her mother is probably never coming back, even taking in a melancholy hitchhiker whose made up backstory she instantly sees through – Futaba is the kind of woman with the instant ability to figure out where it hurts and knows what to do to make it better even if it may be harder in the short-term.

Like the majority of hahamono, however, Her Love Boils Bathwater (湯を沸かすほどの熱い愛, Yu wo Wakasu Hodo no Atsui Ai) can’t escape its inevitable tragedy as someone who’s given so much of themselves is cruelly robbed of the chance to see her labours bear fruit. Nakano reins in the sentimentality as much as possible, but it’s impossible not to be moved by Miyazawa’s nuanced performance which never allows Futaba to slip into the trap of saintliness despite her inherent goodness. She is evenly matched by relative newcomer Sugisaki in the difficult role of the teenage daughter saddled with finding herself and losing her mother at the same time while Aoi Ito does much the same with an equally demanding role for a young actress moving from sullen silence to cheerful acceptance mixed with impending grief. Yet what lingers is the light someone like Futaba casts into the world, teaching others to be the best version of themselves and then helping them pass that on in an infinite cycle of interdependence. Hers is a love of all mankind as unconditional as any mother’s, sometimes tough but always forgiving.

Her Love Boils Bathwater was screened at the 17th Nippon Connection Film Festival.

Original trailer (turn on captions for English subtitles)

Like the rest of the world, China, or a given generation at least, may be finding itself at something of a crossroads. The past few years have seen a flurry of coming of age dramas in which the melancholy and middle-aged revisit lost love from their youth but Derek Tsang’s Soul Mate (七月与安生, Qīyuè yǔ Anshēng) seems to be speaking to an older kind of melodrama in its examination of passionate friendship pulled apart by time, tragedy, and unspoken emotion. The story is an old one, but Tsang tells it well as its twin heroines maintain their intense, elemental connection even whilst cruelly separated.

Like the rest of the world, China, or a given generation at least, may be finding itself at something of a crossroads. The past few years have seen a flurry of coming of age dramas in which the melancholy and middle-aged revisit lost love from their youth but Derek Tsang’s Soul Mate (七月与安生, Qīyuè yǔ Anshēng) seems to be speaking to an older kind of melodrama in its examination of passionate friendship pulled apart by time, tragedy, and unspoken emotion. The story is an old one, but Tsang tells it well as its twin heroines maintain their intense, elemental connection even whilst cruelly separated. Feng Xiaogang, often likened to the “Chinese Spielberg”, has spent much of his career creating giant box office hits and crowd pleasing pop culture phenomenons from World Without Thieves to Cell Phone and You Are the One. Looking at his later career which includes such “patriotic” fare as Aftershock, Assembly, and

Feng Xiaogang, often likened to the “Chinese Spielberg”, has spent much of his career creating giant box office hits and crowd pleasing pop culture phenomenons from World Without Thieves to Cell Phone and You Are the One. Looking at his later career which includes such “patriotic” fare as Aftershock, Assembly, and  Youth looks ahead to age with eyes full of hope and expectation, but age looks back with pity and disappointment. Adapting her father’s novel, Liu Yulin joins the recent movement of disillusionment epics coming out of China with Someone to Talk to (一句頂一萬句, Yī Jù Dǐng Yīwàn Jù). Arriving at the same time as another adaptation of a Liu Zhenyun novel, I am Not Madame Bovary, Someone to Talk to takes a less comical look at the modern Chinese marriage with all of its attendant sorrows and ironies, a necessity and yet the force which both defines and ruins lives. Communism believes love is a bourgeois distraction and the enemy of the common good (it may have a point), but each of these lonely souls craves romantic fulfilment, a soulmate with whom they might not need to talk. The desire for someone they can connect with an elemental level becomes the one thing they cannot live without.

Youth looks ahead to age with eyes full of hope and expectation, but age looks back with pity and disappointment. Adapting her father’s novel, Liu Yulin joins the recent movement of disillusionment epics coming out of China with Someone to Talk to (一句頂一萬句, Yī Jù Dǐng Yīwàn Jù). Arriving at the same time as another adaptation of a Liu Zhenyun novel, I am Not Madame Bovary, Someone to Talk to takes a less comical look at the modern Chinese marriage with all of its attendant sorrows and ironies, a necessity and yet the force which both defines and ruins lives. Communism believes love is a bourgeois distraction and the enemy of the common good (it may have a point), but each of these lonely souls craves romantic fulfilment, a soulmate with whom they might not need to talk. The desire for someone they can connect with an elemental level becomes the one thing they cannot live without.

Corruption has become a major theme in Korean cinema. Perhaps understandably given current events, but you’ll have to look hard to find anyone occupying a high level corporate, political, or judicial position who can be counted worthy of public trust in any Korean film from the democratic era. Cho Ui-seok’s Master (마스터) goes further than most in building its case higher and harder as its sleazy, heartless, conman of an antagonist casts himself onto the world stage as some kind of international megastar promising riches to the poor all the while planning to deprive them of what little they have. The forces which oppose him, cerebral cops from the financial fraud devision, may be committed to exposing his criminality but they aren’t above playing his game to do it.

Corruption has become a major theme in Korean cinema. Perhaps understandably given current events, but you’ll have to look hard to find anyone occupying a high level corporate, political, or judicial position who can be counted worthy of public trust in any Korean film from the democratic era. Cho Ui-seok’s Master (마스터) goes further than most in building its case higher and harder as its sleazy, heartless, conman of an antagonist casts himself onto the world stage as some kind of international megastar promising riches to the poor all the while planning to deprive them of what little they have. The forces which oppose him, cerebral cops from the financial fraud devision, may be committed to exposing his criminality but they aren’t above playing his game to do it.

“Time, like a river, flows both day and night” as the narrator of Yang Chao’s poetical return to source Crosscurrent (長江圖, Chang Jiang Tu) tells us early on. Like the crosscurrent of the title, ship’s captain Chun sails forth yet also in retrograde as he chases a love he can never truly embrace. Truth be told, the philosophical poetry of a lonely sailor condemned to sail a predetermined course at the mercy of the winds and tides is often obscure and confused, like the half mad ramblings of one who’s spent too much time all alone at sea. Yet his melancholy passage is more metaphor than reality, or several interconnected metaphors as water yearns for shore but is pulled towards the ocean, a man yearns to free himself of his father’s spirit, and mankind yearns for the land yet disrupts and destroys it in its quest for mastery. Often frustrating in its obscurity, Crosscurrent’s breathtaking visuals are the key to unlocking its meditative sadness as they paint the beautiful landscape in its own conflicting colours.

“Time, like a river, flows both day and night” as the narrator of Yang Chao’s poetical return to source Crosscurrent (長江圖, Chang Jiang Tu) tells us early on. Like the crosscurrent of the title, ship’s captain Chun sails forth yet also in retrograde as he chases a love he can never truly embrace. Truth be told, the philosophical poetry of a lonely sailor condemned to sail a predetermined course at the mercy of the winds and tides is often obscure and confused, like the half mad ramblings of one who’s spent too much time all alone at sea. Yet his melancholy passage is more metaphor than reality, or several interconnected metaphors as water yearns for shore but is pulled towards the ocean, a man yearns to free himself of his father’s spirit, and mankind yearns for the land yet disrupts and destroys it in its quest for mastery. Often frustrating in its obscurity, Crosscurrent’s breathtaking visuals are the key to unlocking its meditative sadness as they paint the beautiful landscape in its own conflicting colours.

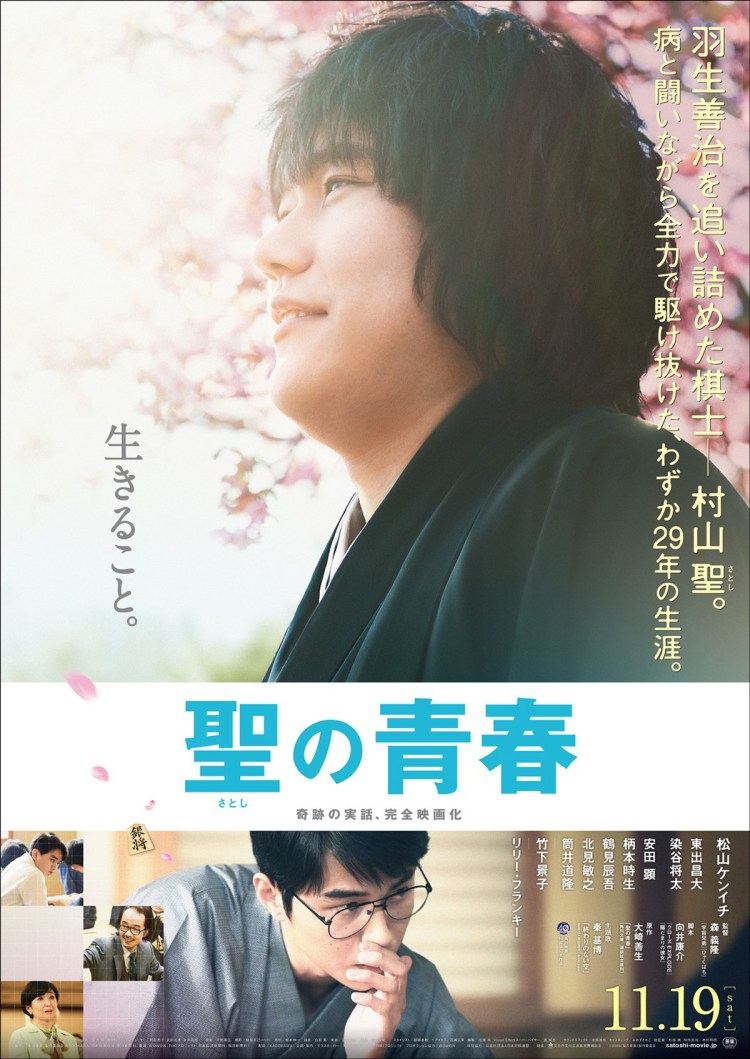

There’s a slight irony in the English title of Yoshitaka Mori’s tragic shogi star biopic, Satoshi: A Move For Tomorrow (聖の青春, Satoshi no Seishun). The Japanese title does something similar with the simple “Satoshi’s Youth” but both undercut the fact that Satoshi (Kenichi Matsuyama) was a man who only ever had his youth and knew there was no future for him to consider. The fact that he devoted his short life to a game that’s all about thinking ahead is another wry irony but one it seems the man himself may have enjoyed. Satoshi Murayama, a household name in Japan, died at only 29 years old after denying chemotherapy treatment for bladder cancer in fear that it would interfere with his thought process and set him back on his quest to conquer the world of shogi. Less a story of triumph over adversity than of noble perseverance, Satoshi lacks the classic underdog beats the odds narrative so central to the sports drama but never quite manages to replace it with something deeper.

There’s a slight irony in the English title of Yoshitaka Mori’s tragic shogi star biopic, Satoshi: A Move For Tomorrow (聖の青春, Satoshi no Seishun). The Japanese title does something similar with the simple “Satoshi’s Youth” but both undercut the fact that Satoshi (Kenichi Matsuyama) was a man who only ever had his youth and knew there was no future for him to consider. The fact that he devoted his short life to a game that’s all about thinking ahead is another wry irony but one it seems the man himself may have enjoyed. Satoshi Murayama, a household name in Japan, died at only 29 years old after denying chemotherapy treatment for bladder cancer in fear that it would interfere with his thought process and set him back on his quest to conquer the world of shogi. Less a story of triumph over adversity than of noble perseverance, Satoshi lacks the classic underdog beats the odds narrative so central to the sports drama but never quite manages to replace it with something deeper. Every keen dramatist knows the most exciting things which happen at a party are always those which occur away from the main action. Lonely cigarette breaks and kitchen conversations give rise to the most unexpected of events as those desperately trying to escape the party atmosphere accidentally let their guard down in their sudden relief. Adapting his own stage play titled Trois Grotesque, Kenji Yamauchi takes this idea to its natural conclusion in At the Terrace (テラスにて, Terrace Nite) setting the entirety of the action on the rear terraced area of an elegant European-style villa shortly after the majority of guests have departed following a business themed dinner party. This farcical comedy of manners neatly sends up the various layers of propriety and the difficulty of maintaining strict social codes amongst a group of intimate strangers, lending a Japanese twist to a well honed European tradition.

Every keen dramatist knows the most exciting things which happen at a party are always those which occur away from the main action. Lonely cigarette breaks and kitchen conversations give rise to the most unexpected of events as those desperately trying to escape the party atmosphere accidentally let their guard down in their sudden relief. Adapting his own stage play titled Trois Grotesque, Kenji Yamauchi takes this idea to its natural conclusion in At the Terrace (テラスにて, Terrace Nite) setting the entirety of the action on the rear terraced area of an elegant European-style villa shortly after the majority of guests have departed following a business themed dinner party. This farcical comedy of manners neatly sends up the various layers of propriety and the difficulty of maintaining strict social codes amongst a group of intimate strangers, lending a Japanese twist to a well honed European tradition.

Nobuhiro Yamashita may be best known for his laid-back slacker comedies, but he’s no stranger to the darker sides of humanity as evidenced in the oddly hopeful Drudgery Train or the heartbreaking exploration of misplaced trust and disillusionment of My Back Page. One of three films inspired by Hakodate native novelist Yasushi Sato (the other two being Kazuyoshi Kumakiri’s Sketches of Kaitan City and Mipo O’s The Light Shines Only There), Over the Fence (オーバー・フェンス) may be among the less pessimistic adaptations of the author’s work though its cast of lonely lost souls is certainly worthy both of Yamashita’s more melancholy aspects and Sato’s deeply felt despair.

Nobuhiro Yamashita may be best known for his laid-back slacker comedies, but he’s no stranger to the darker sides of humanity as evidenced in the oddly hopeful Drudgery Train or the heartbreaking exploration of misplaced trust and disillusionment of My Back Page. One of three films inspired by Hakodate native novelist Yasushi Sato (the other two being Kazuyoshi Kumakiri’s Sketches of Kaitan City and Mipo O’s The Light Shines Only There), Over the Fence (オーバー・フェンス) may be among the less pessimistic adaptations of the author’s work though its cast of lonely lost souls is certainly worthy both of Yamashita’s more melancholy aspects and Sato’s deeply felt despair. Crazy uncles – the gift that keeps on giving. Following the darker edged Over the Fence as the second of two films released in 2016, Nobuhiro Yamashita’s My Uncle (ぼくのおじさん, Boku no Ojisan) pushes his subtle humour in a much more overt direction with a comic tale of a self obsessed (not quite) professor as seen seen through the eyes of his exasperated nephew. “Travels with my uncle” of a kind, Yamashita’s latest is a pleasantly old fashioned comedy spiced with oddly poignant moments as a wiser than his years nephew attempts to help his continually befuddled uncle navigate the difficulties of unexpected romance.

Crazy uncles – the gift that keeps on giving. Following the darker edged Over the Fence as the second of two films released in 2016, Nobuhiro Yamashita’s My Uncle (ぼくのおじさん, Boku no Ojisan) pushes his subtle humour in a much more overt direction with a comic tale of a self obsessed (not quite) professor as seen seen through the eyes of his exasperated nephew. “Travels with my uncle” of a kind, Yamashita’s latest is a pleasantly old fashioned comedy spiced with oddly poignant moments as a wiser than his years nephew attempts to help his continually befuddled uncle navigate the difficulties of unexpected romance.