Lee Kang-hyun becomes the latest Korean director to question the nature of reality in a rapidly modernising society in the oblique, deliberately confusing Possible Faces (얼굴들, Eolguldeul). Ironically enough, the film’s original Korean title is simply “Faces” and in a nod to the 1968 Cassavetes classic with which it shares its name, takes the breakdown of a relationship as its starting point to examine the parallel lives of former lovers. Circular logic predominates as the simulacrum begins to chew away at the authentic, but even if anyone notices the teeth marks at the edges of reality they may no longer care.

Lee Kang-hyun becomes the latest Korean director to question the nature of reality in a rapidly modernising society in the oblique, deliberately confusing Possible Faces (얼굴들, Eolguldeul). Ironically enough, the film’s original Korean title is simply “Faces” and in a nod to the 1968 Cassavetes classic with which it shares its name, takes the breakdown of a relationship as its starting point to examine the parallel lives of former lovers. Circular logic predominates as the simulacrum begins to chew away at the authentic, but even if anyone notices the teeth marks at the edges of reality they may no longer care.

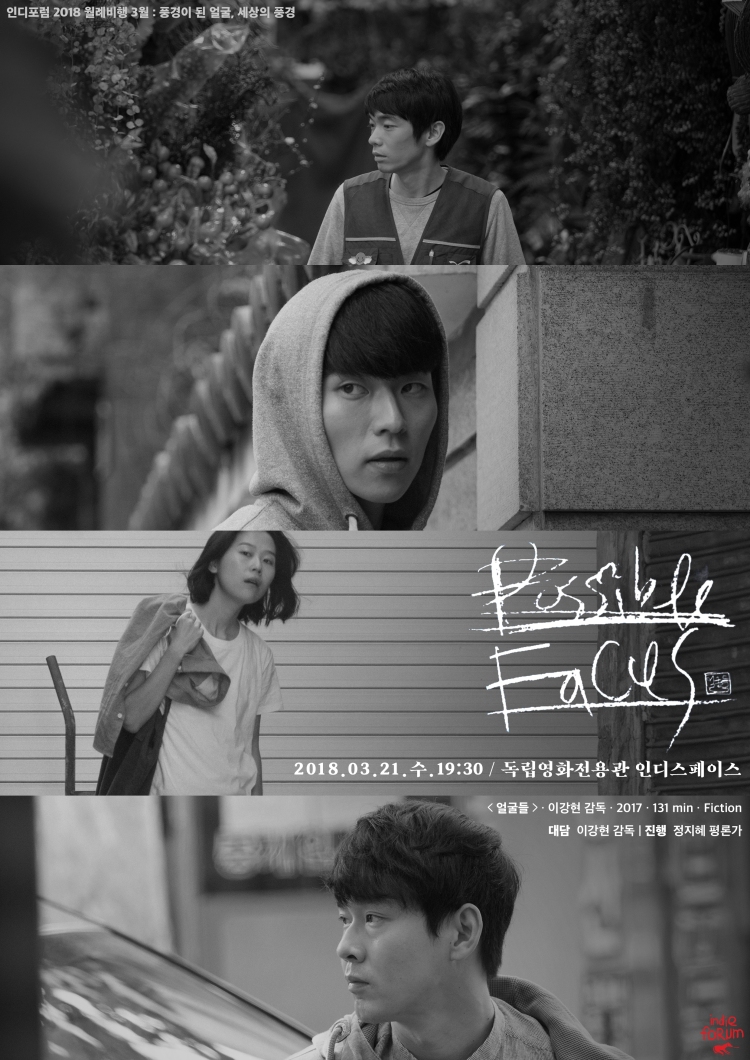

Dejected high school administrator Kisun (Park Jonghwan) has been kicked out of his girlfriend Hyejin’s (Kim Saebyeok) house after three years of cohabitation. It’s really not his area, but handed an incomplete scholarship application form from a soccer team member who routinely dodges classes, he finds himself becoming increasingly invested in the boy’s life. Meanwhile, Hyejin has resigned from her corporate office job to take over her mother’s cheap eats restaurant which she hopes to renovate and turn into a cute little boutique diner. The pair are accidentally connected by the circular motion of Hyunsu, a freelance delivery driver with a romantic heart.

Nothing is quite as it seems. One of Hyun-su’s early deliveries is collecting artificial flowers from a nearby garden centre for a magazine shoot. The regular guy has been moved on, so Hyunsu is the new contact but, as he points out to the saleswoman, though he may be wearing a uniform he is not technically speaking an “employee”. Hyunsu further reinforces his point by asking why none of the other stalls are open – they belong to wholesalers of “real” flowers so they keep specific hours. Sellers of artificial flowers, by contrast, can open 24/7, because their flowers require no maintenance and will never wither, eternally unchanging while the real thing fades. Meanwhile, museums stage reenactments of martial arts performances for tourists, display “replica” artefacts, and boast of the restorations on their “ancient” walls.

The world becomes increasingly “faceless”, as if time is beginning to wear away the surface of reality. Kisun, stuck in a depressive rut, laments that he could stick with his boring admin job for the next 20 years during which time nothing would change except the faces of the kids, as indistinct as they already seem to be. Hyejin walks past the Google Mapping van with a giddy sort of glee as if she’s just spotted a celebrity of whom she is a big fan, calling her friend to share her amazement but lamenting that they will probably blur her face and thereby neuter her newfound immortality. That may not be an altogether bad thing, as Hyunsu learns on reading a mysterious diary in which a woman makes cheerful fun of her husband for mildly resembling a wanted poster on the way out of the park.

The more things change, the more we want them to stay the same, only “better”. Hyejin quits her job to take over the family restaurant despite her mother’s misgivings, but she remakes it in her own image, giving it an upscale makeover in the process. She walks through run down shopping arcades and becomes a tourist in her own city, admiring the old world charm of narrow winding streets untouched by the neon lights of chain stores and comes home to plug in a dull LED lamp to write in her notebook with an old-fashioned fountain pen as if by candlelight.

Hyejin is moving backwards to move forwards, but Kisun is struggling to move at all. He jacks in his boring admin job to join a magazine dedicated to selling the charms of everyday life repackaged as marketable luxuries, complete with Kisun’s own poetic copy gracing the front cover. He finds himself on a kafkaesque quest chasing Schrödinger’s executive who always seems to be away from his desk before eventually tracking him down to a strange cultural event only to realise it isn’t him at all only after he’s been given the portentous advice to ditch his special issue feature for one on the soccer kid from the beginning, Jinsu. While Kisun meanders, Jinsu seems to have made something of himself. Years seem to have passed, but according to Hyejin’s diary it’s only been a few months – months of industry for some perhaps, if only slow months of drudgery for others. The world of Lee’s Possible Faces is one spiralling away from itself in which the nature of reality, identity, and objective truth has become indistinct, to the degree that it has become a mere simulacrum of itself in which the uncanniness of the real provokes only discomfort in its natural imperfections.

Possible Faces was screened as part of the 2018 London Korean Film Festival.

Interview with director Lee Kang-hyun from the 2017 Busan Film Festival.