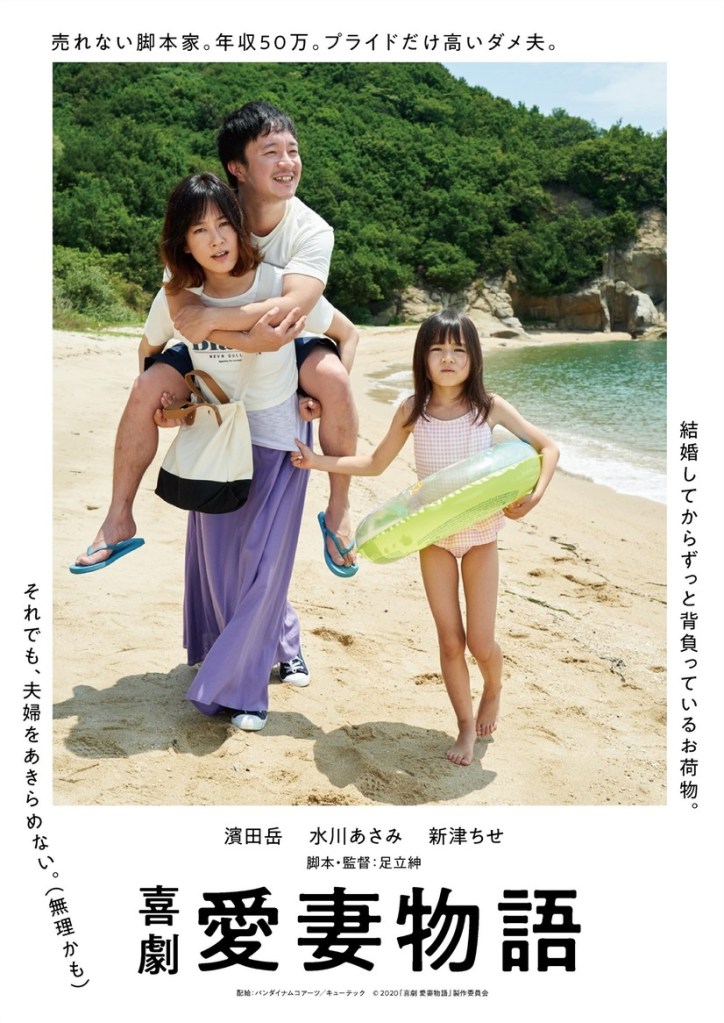

Adapting his own autobiographical novel, screenwriter and director Shin Adachi claims that the events and characters of A Beloved Wife (喜劇 愛妻物語, Kigeki Aisai Monogatari) are exactly as they are in real life, only the film makes it all look better. Even if true, Adachi can’t be faulted for his honesty. His protagonist stand-in, Gota (Gaku Hamada), has almost no redeeming qualities, while his long-suffering wife receives little sympathy even while giving as good as she gets as a sake-guzzling harridan apparently ready to run her husband down at every opportunity, of which there are many, but Gota is quite simply useless. The Japanese title is careful to include the word “comedy” as a prefix, but this is humour of an extremely cruel variety.

Married for 10 years with a small daughter, Gota’s chief preoccupation in his life seems to be that his wife, Chika (Asami Mizukawa), no longer finds him sexually desirable and they are rarely intimate. Rather than lament the distance in their marriage, all Gota does is go on a long, misogynistic rant about how he’d get a mistress or visit a sex worker only he has no money while complaining that he has to humiliate himself by helping out with the housework and childcare which he only does to curry favour in the hope that he will eventually be able to have sex with his wife. After some minor success as a screenwriter, his career is on the slide and he’s had no work in months, something which seems to damage his sense of masculinity and in his mind contributes to his wife’s animosity towards him.

He is right in one regard in that Chika is thoroughly fed up being forced to pick up the slack while he sits around watching VR porn, not writing or looking for a job but insisting that the next movie is always just round the corner. She’s tired and overworked, sick of penny pinching and resentful that she has to do everything herself, but it’s not so much the money that bothers her as Gota’s fecklessness while all he seems to care about is sex, meeting his own needs and no one else’s. Even when he takes his daughter, Aki (Chise Niitsu), to the park he ignores her to ogle other women, becoming embarrassed on running into a neighbour we later learn he slept with and then ghosted. He does the same thing again later on a beach, so busy sexting that he doesn’t see her wander off and is roundly chewed out by the lifeguard (an amusing cameo from director Hirobumi Watanabe, giving him the hard stare) who eventually finds her and brings her back. Not content with that, he rounds out the bad dad card by frequently bribing Aki with treats so she won’t spill the beans to her mum about his many questionable parental decisions.

Really, we have to ask ourselves, why does Chika not leave him? The perspective we’re given is Gota’s and he appears not to understand that any of his behaviour is problematic, which might be why he seems genuinely shocked when Chika reaches the end of her tether and once again suggests divorce. He seems to think some of this at least is performative, part of the act of “marriage”, and she does indeed make a show of her frugality – insisting on sharing a 200 yen bowl of udon with her daughter to save money and climbing up a utility pole to sneak into a hotel after booking only a single occupancy room for the three of them, but is there more in her decision not to leave than habit? Gota seems to think so, especially on noticing her wearing the lucky red pants she bought back when they were young and in love and she believed in his potential. But then perhaps she really is just being economical.

Nevertheless, she appears to keep supporting him, once again typing up his latest screenplay because he claims not to be able to use a word processor, and laughing off the rather more serious incident in which he is arrested after being discovered by a policeman molesting a drunk woman in the street. Adachi doesn’t appear to have very much to say in favour of the modern marriage, as if this one is no worse than any other (even a friend who married well (Kaho) badmouths her husband and giggles about a young lover), but Gota seems to have learned absolutely nothing even while declaring his love to his sleeping family and vowing to make a success of himself at last. It would be funny, if it weren’t so sad.

A Beloved Wife is available to stream worldwide until July 4 as part of this year’s Udine Far East Film Festival.

Festival trailer (English subtitles)