“We never had a country” a student at a North Korean school in Japan fires back, hinting at his feelings of displacement in being asked to remain loyal to a place he never knew while the culture in which he was born and raised often refuses to accept him. The hero of Isao Yukisada’s Go is not so much searching for an identity as a right to be himself regardless of the labels that are placed on him but is forced to contend with various layers of prejudice and discrimination in a rigidly conformist society.

As he points out, when they call him “Zainichi” it makes it sound as if he is only a “temporary resident” who does not really belong in Japan and will eventually “return” to his “home culture”. In essence, “Zainichi” refers to people of Korean ethnicity who came to Japan during the colonial era and their descendants who are subject to a special immigration status which grants them rights of residency but not citizenship. Sugihara’s (Yosuke Kubozuka) situation is complicated by the fact that his father (Tsutomu Yamazaki) has a North Korean passport, making him a minority even with the Korean-Japanese community. He attends a North Korean school where speaking Japanese is forbidden and is educated in the tenets of revolutionary thought which are of course entirely contrary to the consumerist capitalism of contemporary Japan.

His father eventually consents to swap his North Korean passport for a South Korean one mostly it seems so he can take a trip to Hawaii with his wife (Shinobu Otake) which seems to Sugihara a trivial reason for making such a big decision especially as it caused the lines of communication to break down with his bother who returned to North. Yet it seems like what each of them is seeking is an expansion of internal borders, the right not to feel bound by questions of national identity in order to live in a place of their own choosing. “I felt like a person for the first time,” Sugihara explains on being given the opportunity to choose his nationality even if it is only the “narrow” choice between North and South Korea.

But on the other hand he wonders if it would make his life easier if he had green skin so that his “non-Japaneseness” would be obvious. Sugihara reminds us several times that this is a love story, but he delays revealing that he is a Zainichi Korean to his girlfriend because he fears she will reject him once she knows. On visiting Sakurai’s (Ko Shibasaki) home, it becomes obvious that she comes from a relatively wealthy, somewhat conservative family. Her father, who is unaware Sugihara is Korean-Japanese, immediately asks him if he likes “this country” but is irritated when Sugihara asks him if he really knows the meaning behind the various words for “Japan” again hinting at the meaninglessness of such distinctions. When he eventually does tell Sakurai that he is ethnically Korean, her reaction surprises both of them as she recalls her father telling her not to date Korean or Chinese men on account of their “dirty” blood.

Such outdated views are unfortunately all too common even at the dawn of the new millennium. Even so, Sakurai had not wanted to reveal her full name because she was embarrassed that it is so “very Japanese” while conversely Sugihara takes ownership of the name “Lee Jong-ho”. He embraces the “very Japanese” tradition of rakugo, and hangs out in the Korean restaurant where his mother works dressed in vibrant hanbok. Given a book of Shakespeare by his studious friend, he is struck by the quote which opens the film which states that a rose by any other name would smell as sweet and wonders what difference a name makes when its the same person underneath it.

Perhaps his father’s admission that he always found a way to win wasn’t so off base after all, nor his eventual concession that Sugihara may have it right when he rejects all this talk of “Zainichi” and “Japanese” as “bullshit” and resolves to “wipe out borders”. He insists on being “himself” or perhaps a giant question mark, and discovers that Sakurai may have come to the same conclusion in realising that all that really mattered was what she saw and felt. Yukisada captures the anxieties of the age in the pulsing rhythms of his youthful tale which keeps its heroes always on the run, but is in the end a love story after all and filled with an equally charming romanticism.

GO is released on blu-ray in the UK on 22nd May courtesy of Third Window Films.

Original trailer (English subtitles)

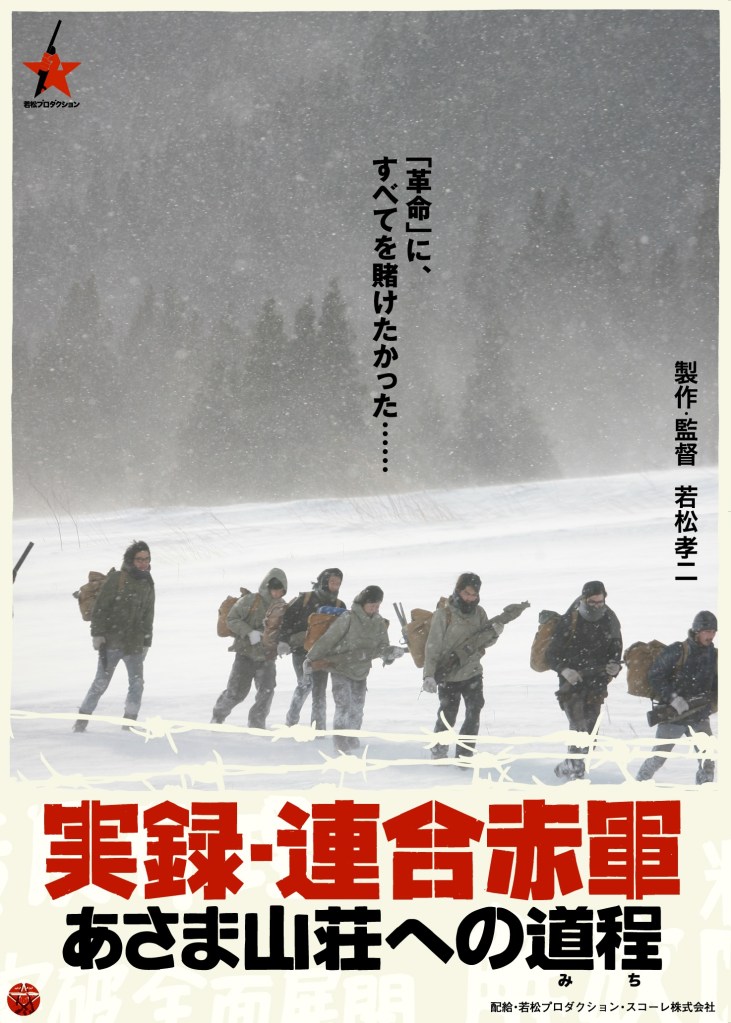

Koji Wakamtasu had a long and somewhat strange career, untimely ended by his death in a road traffic accident at the age of 76 with projects still in the pipeline destined never to be finished. 2008’s United Red Army (実録・連合赤軍 あさま山荘への道程, Jitsuroku Rengosekigun Asama-Sanso e no Michi) was far from his final film either in conception or actuality, but it does serve as a fitting epitaph for his oeuvre in its unflinching determination to tell the sad story of Japan’s leftist protest movement. Having been a member of the movement himself (though the extent to which he participated directly is unclear), Wakamatsu was perfectly placed to offer a subjective view of the scene, why and how it developed as it did and took the route it went on to take. This is not a story of revolution frustrated by the inevitability of defeat, there is no romance here – only the tragedy of young lives cut short by a war every bit as pointless as the one which they claimed to be in protest of. Young men and women who only wanted to create a better, fairer world found themselves indoctrinated into a fundamentalist political cult, misused by power hungry ideologues whose sole aims amounted to a war on their own souls, and finally martyred in an ongoing campaign of senseless death and violence.

Koji Wakamtasu had a long and somewhat strange career, untimely ended by his death in a road traffic accident at the age of 76 with projects still in the pipeline destined never to be finished. 2008’s United Red Army (実録・連合赤軍 あさま山荘への道程, Jitsuroku Rengosekigun Asama-Sanso e no Michi) was far from his final film either in conception or actuality, but it does serve as a fitting epitaph for his oeuvre in its unflinching determination to tell the sad story of Japan’s leftist protest movement. Having been a member of the movement himself (though the extent to which he participated directly is unclear), Wakamatsu was perfectly placed to offer a subjective view of the scene, why and how it developed as it did and took the route it went on to take. This is not a story of revolution frustrated by the inevitability of defeat, there is no romance here – only the tragedy of young lives cut short by a war every bit as pointless as the one which they claimed to be in protest of. Young men and women who only wanted to create a better, fairer world found themselves indoctrinated into a fundamentalist political cult, misused by power hungry ideologues whose sole aims amounted to a war on their own souls, and finally martyred in an ongoing campaign of senseless death and violence.