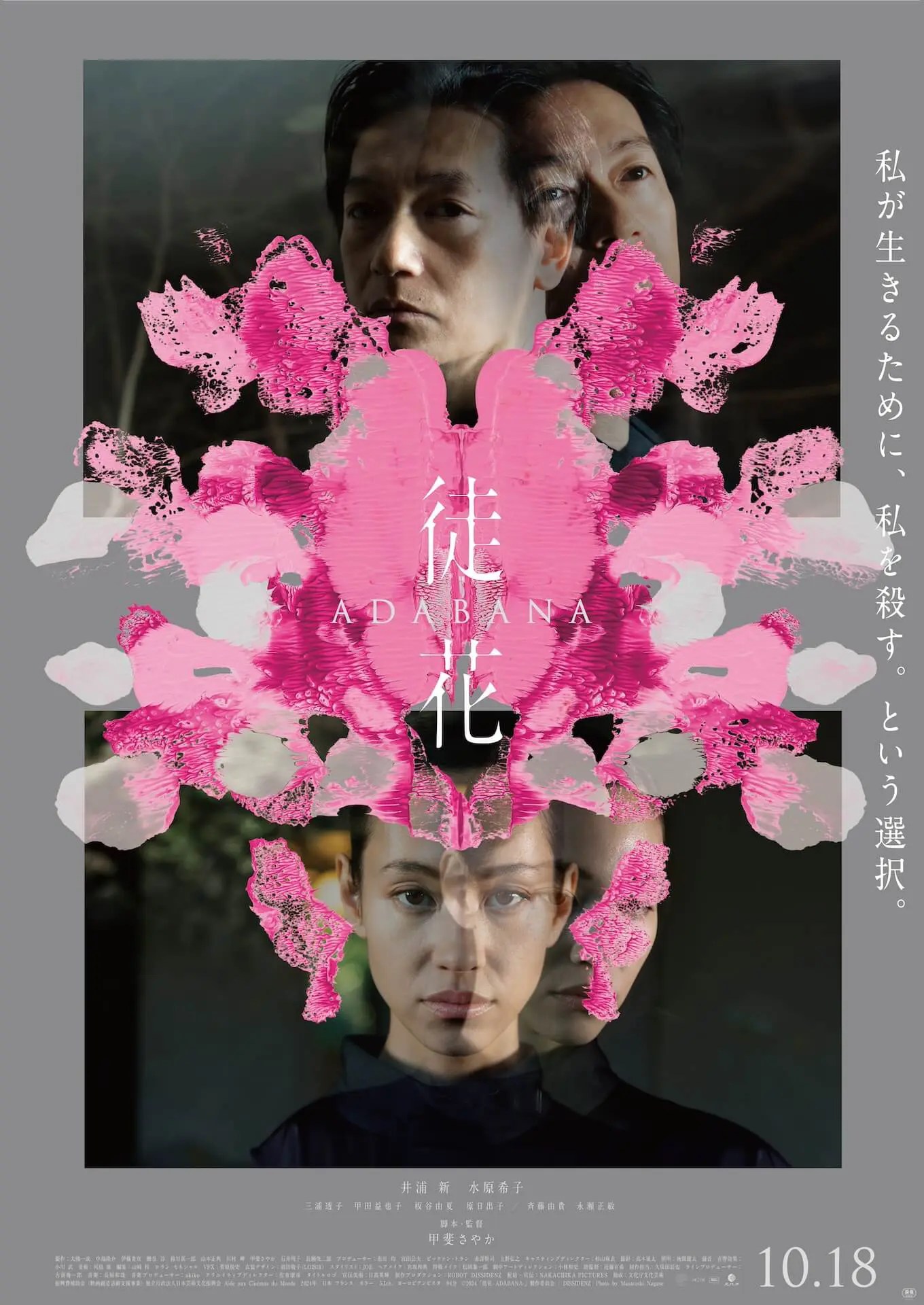

What constitutes a good life? Is it what you leave behind, or the experience of comfort and contentment? The Adabana of Sayaka Kai’s existential drama refers to a barren flower that will never bear fruit and is intended to survive for only one generation, yet its life is not without meaning and for the time that is alive, it is beautiful. Accepting the burden of death can be liberating, while the burden of life provokes only suffering born or constraint.

Or at least, the conflicted Shinji (Arata Iura) has begun to contemplate after becoming terminally ill pressured to undergo surgery that will save his life at the cost of his “unit”, a kind of clone intended for the provision of spare parts should their individual encounter some kind of medical issue. In this world, a virus has inhibited human reproduction and led to a desire to prolong life in order to provide a workforce. This is done largely through the use of clones, though it’s clear to us right away that this is a technology only accessible to the wealthy elite.

In the Japanese, the units are referred to euphemistically as “sore” or “that”, as if their presence was slightly taboo and Shinji is encouraged to view his not as a person but as a thing to be used when needed, like a replacement battery or parts for an engine. Nevertheless, it nags at him that another being will die for him to live. The hospital director instructs him that he cannot die because he is important as the heir to this company which suggests both that his existence is more valuable than others and that he is actually worth nothing at all outside of his role as the incarnation of a corporation. Kai often presents Shinji and his clone on opposite sides of the glass as if they were mere reflections of each other or two parts of one whole. Their existences could easily have been switched and either one of them could have been designated the “unit” or “original”.

On Shinji’s side of the glass, the world is cold and clinical. He feels constrained by his upper class upbringing and feels as if he is ill-suited to this kind of life. He has flashbacks to a failed romance with a free-spirited bar owner (Toko Miura) whom he evidently abandoned to fulfil parental expectations through an arranged marriage deemed beneficial to the family’s corporate interests. He has one daughter, but has no feelings for his wife and resents his circumstances. Beyond the glass, meanwhile, is a kind of pastoral paradise where his unit fulfils himself with art, though Shinji never had any artistic aptitude of his own. The unit says that there was a female unit he can’t forget who was taken seven years ago hinting at his own sad romance, yet he’s completely at peace with the idea that his purpose in life was only to give it up so that Shinji might live. In the surgery, he will achieve his life’s purpose, though Shinji is beginning to see it only as a prolongation of his suffering.

The unit’s speech is soft and slightly effeminate in contrast with the suppressed rage and nervousness that characterise Shinji’s way of speaking, and what becomes clear to Shinji is the ways in which they’re different rather than the same. He wonders if his unit would be kinder to his family and more able to adapt to this way of life from which he desires to be liberated. His psychiatrist, Mahoro (Kiko Mizuhara), too finds herself conflicted by his interactions with his unit beginning to wonder what her own nature and purpose might be. The units are shown videos featuring the memories of their originals, though apparently only the good parts, which suggests that in some cases the original actually dies and is replaced as if they and the unit were otherwise interchangeable with the unit learning to perform a new role despite having had completely different life experiences that are only partially overwritten by a memory transfer. What is it then that makes us “us”, if not for our memories both good and bad? On watching her own tape, Mahoro feels as if it’s somehow changed her, resulting in a nagging uncertainty about things unremembered coupled with the pressures of being under constant surveillance. For Shinji at least, it may be that he too sees liberation in death and envies a life of fruitless simplicity over his own of suffering and constraint.

Adabana screens as part of this year’s Japan Foundation Touring Film Programme.

Trailer (no subtitles)

Images: © 2024 ADABANA FILM PARTNERS _ DISSIDENZ