“The things you learn as a child stay with you” admits a melancholy nursery teacher, lamenting that perhaps her life would have turned out differently if only her parents hadn’t been so easy going. Most people probably wind up wondering something similar, who they might have been if their parents had or hadn’t made the choices that they made on their behalf, but sooner or later you have to leave childhood behind and take responsibility for yourself.

That’s the part that the heroine of Aya Miyazaki’s Good-bye (グッドバイ), 20-something Sakura (Mayuko Fukuda), is currently having trouble with, struggling to find a way forward largely because in one sense everything comes too easy for her and life is no kind of challenge. Privately, however, she’s caught in an adolescent dilemma pining for the father who, it seems, has been largely absent from her life since leaving the family when she was small.

The crunch comes when Sakura abruptly quits yet another boring office job just because it didn’t light her fire. Her mystified friend who can’t really believe someone would just quit their job on a whim in Japan’s competitive employment environment just because it was dull (let alone make a habit of it), suggests she fill in at a daycare centre that another friend has just vacated leaving them in the lurch and with a temporary contract available. Sakura is unconvinced seeing as she has no childcare qualifications, but is persuaded on hearing the facility is “unlicensed” and therefore not fussy. She doesn’t exactly take to it right away, but beginning to bond with the children reminds her of her more innocent self, especially once she encounters the father of one little girl, Ai, who is often the last to get picked up.

Sakura is taken with Mr. Shindo (Kohei Ikeue) because he looks a little like her dad and also smells of the same brand of cherry-scented cigars that he used to smoke. It also doesn’t help that his family situation closely resembles a mildly traumatic incident from her own childhood in that Ai’s mum seems to be temporarily absent from the family home for unclear reasons. Sakura finds herself playing mother, brushing Ai’s hair and tying it up in pigtails the way her father couldn’t quite master on his own. Running into the pair in the street, she even finds herself cooking dinner for them, giving Ai a few lessons in peeling carrots, while accidentally stepping into the space vacated by another woman and perhaps crossing a line with the extremely awkward Mr. Shindo.

The encounter does, however, prompt her into a long delayed conversation with her sympathetic mother (Asako Kobayashi) who offers no explanation for why she did what she did, or sees any need to apologise, but is perhaps touched by some of her words which convince her that her daughter needs a final push to help find her place in the world. Prompted by the other teacher at the nursery, Sakura asks her mother why she sent her to all those after school clubs etc, only to be told that she did it because she wanted Sakura to find her passion but though she was good at everything, Sakura always quit after only a few weeks. Her mother wonders if that’s because when everything is easy for you you have no incentive to stick with it and never get the opportunity to become invested.

That has perhaps been Sakura’s problem, she says goodbye too early before there’s any possibility of getting attached. Bonding with the kids reminds her of the little girl she once was, processing the sudden absence of her mother and the possibility of her familiar world ending. Her mother eventually returned, but perhaps gave her an incomplete sense of security in the feeling that she would never leave her or the house, while her father is of the opinion that the family photo was something best left behind in the family home which was no longer his. In learning to say “good-bye” to Ai, Sakura learns to bid farewell to the little girl she once was, insecure and afraid of rejection. As her mum tries to hint, it’s time for her to find a place of her own, no longer so afraid to stick around past the part where everything seems too easy.

Good-bye screened as part of this year’s Osaka Asian Film Festival.

The Midnight Diner is open for business once again. Yaro Abe’s eponymous manga was first adapted as a TV drama in 2009 which then ran for three seasons before heading to the

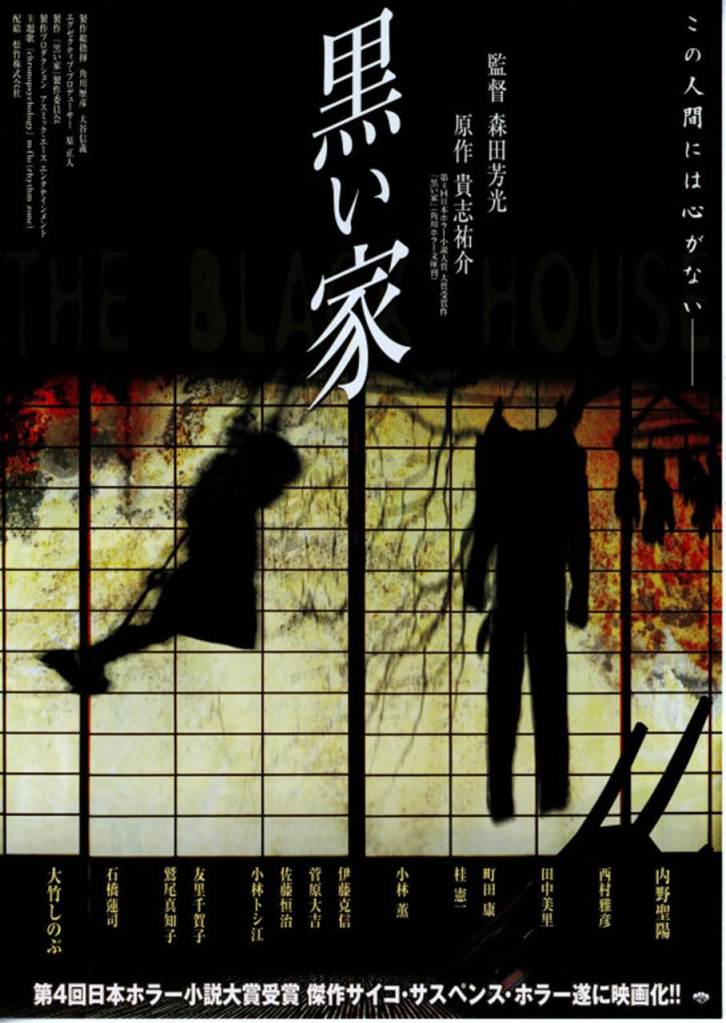

The Midnight Diner is open for business once again. Yaro Abe’s eponymous manga was first adapted as a TV drama in 2009 which then ran for three seasons before heading to the  Yoshimitsu Morita, though committed to commercial filmmaking, also enjoyed trying on different kinds of directorial hats from from purveyor of smart social satires to teen idol movies, high art literary adaptations and just about everything else in-between. It’s no surprise then that at the height of the J-horror boom, he too got in on the action with an adaptation of Yusuke Kishi’s novel of the same name, The Black House (黒い家, Kuroi Ie). Though tagged as “J-horror” you’ll find no long haired ghosts here and, in fact, barely anything supernatural as the true horror on show is the slow descent into madness taking place inside the protagonist’s mind.

Yoshimitsu Morita, though committed to commercial filmmaking, also enjoyed trying on different kinds of directorial hats from from purveyor of smart social satires to teen idol movies, high art literary adaptations and just about everything else in-between. It’s no surprise then that at the height of the J-horror boom, he too got in on the action with an adaptation of Yusuke Kishi’s novel of the same name, The Black House (黒い家, Kuroi Ie). Though tagged as “J-horror” you’ll find no long haired ghosts here and, in fact, barely anything supernatural as the true horror on show is the slow descent into madness taking place inside the protagonist’s mind. 2009 marked the centenary year of Osamu Dazai, a hugely important figure in the history of Japanese literature who is known for his melancholic stories of depressed, suicidal and drunken young men in contemporary post-war Japan. Villon’s Wife (ヴィヨンの妻 〜桜桃とタンポポ, Villon no Tsuma: Oto to Tampopo) is a semi-autobiographical look at a wife’s devotion to her husband who causes her nothing but suffering thanks to his intense insecurity and seeming desire for death coupled with an inability to successfully commit suicide.

2009 marked the centenary year of Osamu Dazai, a hugely important figure in the history of Japanese literature who is known for his melancholic stories of depressed, suicidal and drunken young men in contemporary post-war Japan. Villon’s Wife (ヴィヨンの妻 〜桜桃とタンポポ, Villon no Tsuma: Oto to Tampopo) is a semi-autobiographical look at a wife’s devotion to her husband who causes her nothing but suffering thanks to his intense insecurity and seeming desire for death coupled with an inability to successfully commit suicide. “Why do we have to make such sacrifices for our children?”. It sounds a little cold, doesn’t it, but none the less true. Yoshimitsu Morita’s 1983 social satire The Family Game (家族ゲーム, Kazoku Game) takes that most Japanese of genres, the family drama, and turns it inside out whilst vigorously shaking it to see what else falls from the pockets.

“Why do we have to make such sacrifices for our children?”. It sounds a little cold, doesn’t it, but none the less true. Yoshimitsu Morita’s 1983 social satire The Family Game (家族ゲーム, Kazoku Game) takes that most Japanese of genres, the family drama, and turns it inside out whilst vigorously shaking it to see what else falls from the pockets. Yaro Abe’s manga Midnight Diner (深夜食堂, Shinya Shokudo) was first adapted as 10 episode TV drama back in 2009 with a second series in 2011 and a third in 2014. With a Korean adaptation in between, the series now finds itself back for second helpings in the form of a big screen adaptation.

Yaro Abe’s manga Midnight Diner (深夜食堂, Shinya Shokudo) was first adapted as 10 episode TV drama back in 2009 with a second series in 2011 and a third in 2014. With a Korean adaptation in between, the series now finds itself back for second helpings in the form of a big screen adaptation.