“There’s bad cheating and good cheating,” according to a little boy who will later become “a magician of words and juggler of lies,” in Kaizo Hayashi’s ethereal fable, Circus Boys (二十世紀少年読本, Nijisseiki shonen Dokuhon). Set in early showa, though the early showa of memory in which many other times intertwine, the film positions the transient site of a circus tent as a roving home for all who need it or are seeking escape from the increasingly heightened atmosphere of the early 1930s. Yet where one of the titular boys chooses to stay and earnestly protect this embattled utopia, his brother chooses to leave and seek his fortune in the outside world.

In fact, it’s Jinta (Hiroshi Mikami) who first becomes preoccupied with their precarious position realising that they’ve been hired to look cute riding the elephant, Hanako, but will soon age out of their allotted role and if they can’t master some other kind of circus trick there may no be a place for them in the big tent. For this reason he’s been training in secret with the idea that he can pass off the skills he’s perfected as innate “talent” so the circus will want to keep him on. Wataru (Jian Xiu), his brother, doesn’t quite approve of his plan. After all, aren’t they essentially tricking the people at the circus into thinking they’re something they’re not? But Jinta assures him it’s like “magic,” the kind that will allow them to stay in their circus home which later comes to seem a place of mysticism or perhaps make-believe on its own.

Thus Wataru walks a fine line. His name means “to cross over,” but he never does. He tries to walk the tightrope before he’s ready and is unbalanced by a storm. Jinta breaks his fall, but also in the process his own ankle. Along with it go his dreams. His foot never heals, and he’ll never fly the trapeze with Wataru like he planned though he keeps his injury a secret from his brother. While Wataru flies with new girl Maria (Michiru Akiyoshi), Jinta becomes a clown, a position he’d previously looked down on and later leaves the circus altogether using his talent for magic and performance to become a snake oil salesman tricking what appear largely to be poor farming communities into buying things like miracle soap and coal that burns for a whole month. This is clearly bad cheating, though he tries to convince himself it’s not while essentially remaking the world around him through his lies.

But he retains his integrity in other ways. After being press-ganged into a yakuza-like guild of street pedlars, he gently excuses himself when invited to dine with a boss and confronted by an odd situation in which his wife has purchased another young woman to be his “plaything.” In a comment on contemporary patriarchal norms, the young woman is referred to as “Omocha,” which literally means “toy,” but also sounds a like a woman’s name because it begins with the character “O” which was used as a polite prefix for female names until the practice faded out after the war. The boss of course treats her like a doll, and even the wife refers to her as an “erotic instrument” she got as a way of managing her husband’s sexual appetites fearing he’d otherwise be seeing sex workers and bring a sexually transmitted disease into their home (and also possibly because she simply doesn’t want to sleep with herself any more than she has to). Referred to only as Omocha the woman has almost no agency and finds a kindred spirit in Jinta (whose name contains the character for “humanity”) because like him she also escapes the hardships of the world through lies and fantasy. “Can two lies make one big truth?” Jinta muses, breaking the codes of Guild as he prepares to rescue another man’s plaything, only it may be more like she rescues him.

Meanwhile, Wataru tries to save the circus even after their ringmaster dies with visions of Jinta on his mind. They plan a wall of death to bring back the crowds, but Wataru’s plan backfires with tragic consequences and it becomes clear he can’t protect their circus family even if it brings back veteran trapeze artists Koji (Yukio Yamato) and Yoshiko (Maki Ishikawa) who agree there’s no other place for them out in the big wide world. The sense of the circus as a safe space was echoed on Maria’s arrival when Jinta had cruelly said she looked a little foreign with the ringmaster assuring her that in here they’re all artists and do not classify people in terms of their race, appearance or nationality. Its unreality, however, is reinforced by the constant backing of Wataru’s shadowplay which sometimes shows things the way people wish they were rather than the way they are. Omocha is later seen holding one of these puppets just as she and Jinta decide to die to free themselves of this hellish existence before Jinta’s surrogate brother figure Hiroshi (Shiro Sano) is forced to kill them for breaking the rules of the guild.

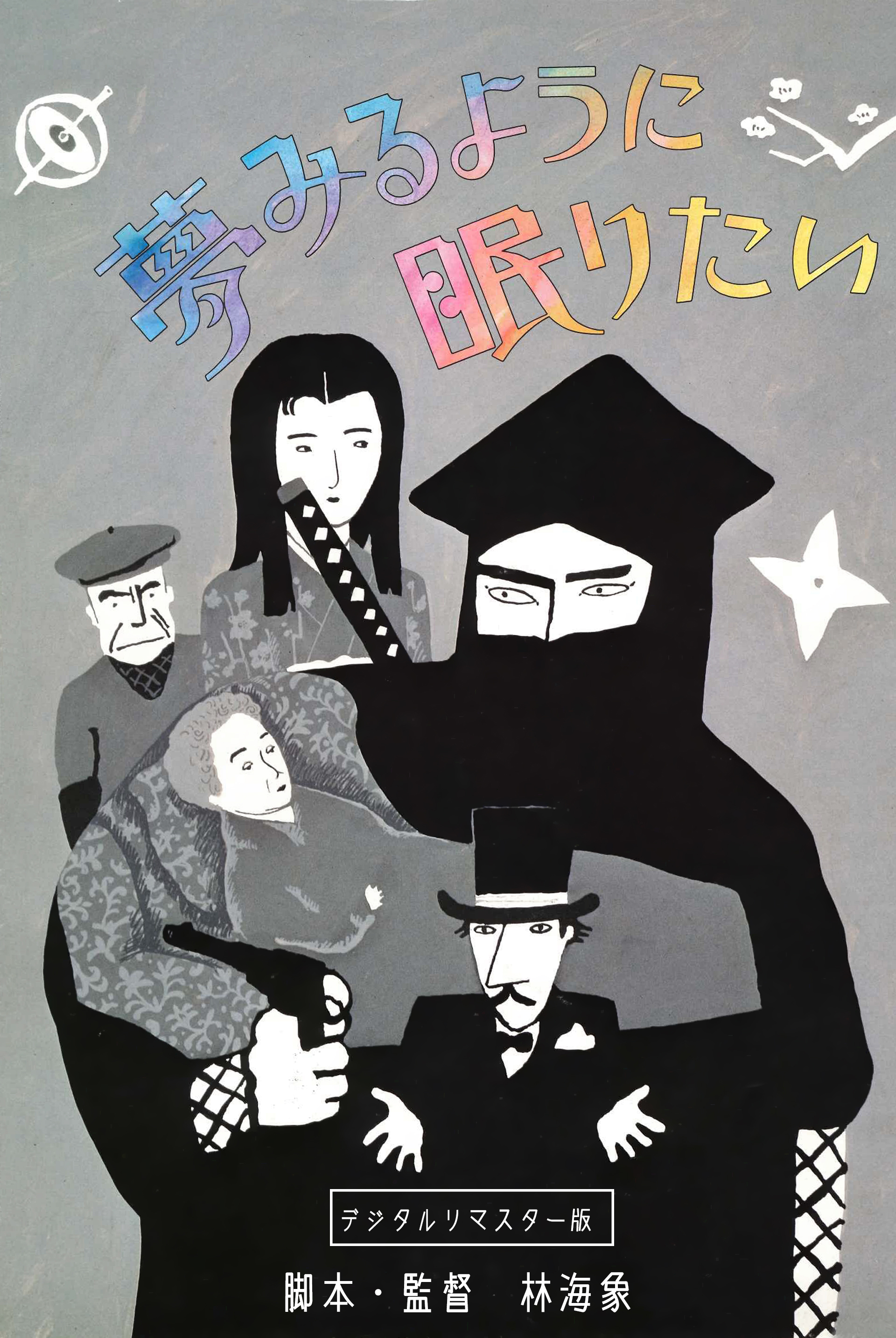

In the ambiguities of the final sequence, we might ask ourselves if they are actually dead and the glowing circus tent they see on the horizon is a path to the afterlife or a kind of heaven represented by the utopia to be found inside it. Then again, perhaps Jinta is merely rediscovering the way home, a prodigal son who now understands he already had a place to belong and there is a place to which he can return. The Great Crescent Circus is now the Sun & Crescent Circus, reflecting the way the two boys inhabit the world like and dark, idealism and cynicism, but comprise two parts of one complete whole. Hayashi waxes self-referential, playfully including a reference to his first film in that the movie playing at the cinema Jinta passes is The Eternal Mystery with Black Mask on his way to rescue Bellflower while indulging in an intense nostalgia for a lost world of travelling shows and hidden magic. Shooting in a beautifully balanced monochrome, he lights on scenes of heart-stopping beauty that are somehow poignant and filled with melancholy but ends with a moment of resolution in which, one way or another, Jinta reaches the promised land as he said with magic.

Circus Boys screens 12th October at Japan Society New York.