The central thesis of Neo Sora’s mildly dystopian drama Happyend is that the real looming earthquake the powers that be are so afraid of is a youth revolution. But the film seems to ask if that’s something that’s really achievable or if idle teenage fantasies of a better world will soon be snuffed out by its seeming impossibility or the internalised desire for a conventionally successful life lived under a system they know to be corrupt, unfair, prejudiced, and staunchly hierarchal.

Thus the school at its centre becomes a microcosm for the society at large. Set slightly in the future, though with a retro sensibility, the film revolves around a close group of friends who are nevertheless pulled in different directions as they approach the end of high school while becoming aware of the destructive effects of an authoritarian educational system on children across the nation. The priggish headmaster (Shiro Sano) is involved in dubious schemes with local government and high tech companies and drives a flashy yellow sports car to work. Somehow the teens manage to prank him by standing it on its end like some kind of monolith to his hypocrisy and corruption. The headmaster quickly brands the obviously harmless prank as a “terrorist” action and uses it to crack down on lapses of discipline in the school.

His actions are mirrored in those of the Prime Minister who uses the looming fear of “the big one” as a means of forwarding his fascitistic agenda. He alludes to the false narrative that Koreans and other minorities committed crimes and poisoned wells in the wake of the 1923 earthquake as justification for his tough approach to immigration while limiting the ability of those who do not hold Japanese citizenship to participate in democracy. Kou (Yukito Hidaka), the most conflicted of the teens is a zainichi Korean whose family as he points out has been in Japan for four generations. He’s not obliged to carry his permanent residency documentation on him, but is repeatedly asked for it by police who scan his face to pull up his records on their ominous new devices. Drawn to rebellious student Fumi (Kilala Inori), he’s minded to resist social oppression but also mindful of his single-mother’s hopes that he will win a scholarship and attend university.

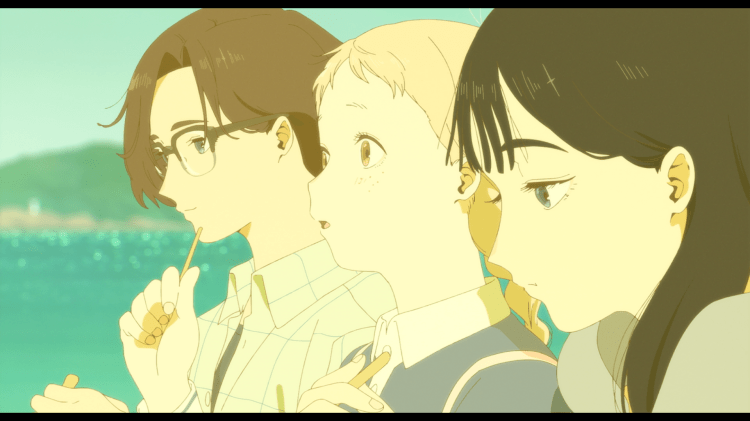

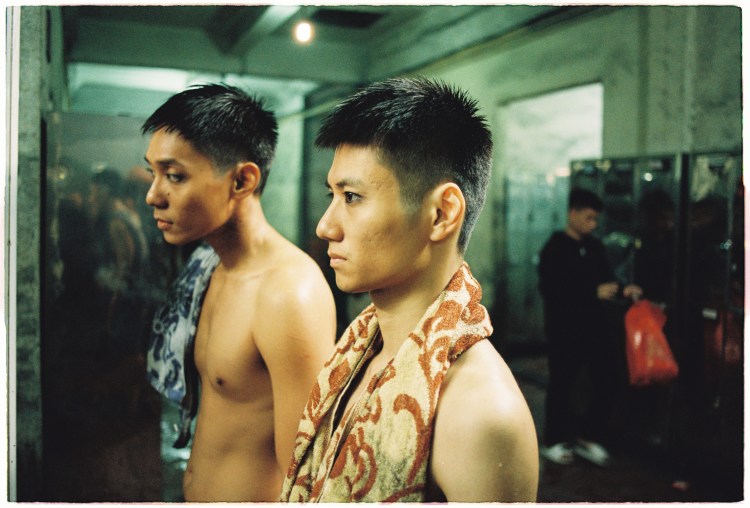

Nevertheless, he begins to drift away from childhood friend Yuta (Yuta Hayashi) who resists by immersing himself in the dance music of the past. Kou regards him as childish or unenlightened, irritated that he doesn’t seem to have grown or changed at all and increasingly convinced he’s outgrown their friendship. There may be something naive about Yuta’s simple desire to enjoy his time with his friends and find his freedom in music, but he is the only one of the teens who really does reject the system by choosing to live outside it.

Tensions come to a head when the school instals a mass surveillance system under the cute name “Panopty,” doubtless inspired by Jeremy Bentham’s famous design for the perfect prison. The system awards points for infractions on discipline but ruthlessly and without thought. A delicious moment sees a telltale baseball student fined once for smoking after picking up a discarded butt with the intention of throwing it away and then again for littering when he inevitably drops it. Led by Fumi, the kids resist in distinctly old-fashioned ways with a sit-in at the headmaster’s office but cracks soon start to appear and some aren’t willing to risk their academic futures on something which will only benefit the kids of tomorrow. In the end they win the right to a free vote on the surveillance system, but have perhaps underestimated how many of the young will also vote for “safety” over freedom in the mistaken belief that the system does not infringe on the rights of people like them.

This is a city in which ominous red lights blink in the distance like silent alarms, where the kids are forever hanging out next to signs that read “caution”, where earthquake alerts are so common no one really pays much attention to them but the looming threat of mass destruction hangs over everything and everyone. Even so, these kids are just teens growing up, having fun with their friends, and beginning to decide which path they’ll take in life. A poignant moment takes place at the end of a bridge with steps on either side and the sense that at some point you go one way and your friend another and you may never see each other again. Perhaps this is their earthquake, the silent tremor that sends them into adulthood and a society still in flux that seems somehow beyond repair.

Happyend screened as part of this year’s BFI London Film Festival.

Original trailer (no subtitles)