The debut film from Yasuzo Masumura, Kisses (くちづけ, Kuchizuke) takes your typical teen love story but strips it of the nihilism and desperation typical of its era. Much more hopeful in terms of tone than its precursor and genre setter Crazed Fruit, or the even grimmer The Warped Ones, Kisses harks back to the more to wistful French New Wave romance (though predating it ever so slightly) as the two youngsters bond through their mutual misfortunes.

The debut film from Yasuzo Masumura, Kisses (くちづけ, Kuchizuke) takes your typical teen love story but strips it of the nihilism and desperation typical of its era. Much more hopeful in terms of tone than its precursor and genre setter Crazed Fruit, or the even grimmer The Warped Ones, Kisses harks back to the more to wistful French New Wave romance (though predating it ever so slightly) as the two youngsters bond through their mutual misfortunes.

The film begins as Kinichi and Akiko experience a meet cute whilst visiting their respective fathers who’ve both landed up in gaol. Kinichi’s dad is a politician who’s been accused of “electoral fraud” which he swears is some kind of plot (even though this is the third time he’s been accused of it) whereas Akiko’s father is a government official who’s embezzled a large sum of money in an act of desperation to pay for her mother’s medical treatment. Just as Kinichi is leaving the prison, Akiko is getting into a situation with the rather rude receptionist because she owes something for her father’s room and board. Kinichi becomes offended on Akiko’s behalf and plonks down more than enough money alongside a few choice words for the lady on the counter before flouncing out. Akiko chases after him with his change even though he tells her to get lost in no uncertain terms. Eventually the two end up spending the day together though things turn a little sour towards the end. In this unlucky world, can two crazy kids ever make it work?

In essence, Kisses is an innocent film. Though there may be a few hints of darkness lurking around the edges, its tone is more or less cheerful and fuelled by the idealism of youth. Both Kinichi and Akiko are realists, they’re both older than their years, put-upon and a little desperate but also a little naive. Kinichi’s grumpy and sullen, perhaps nursing a wound from his mother walking out on him. Even when he asks her for the money to bail his father out of gaol she tells him to grow up before treating him like a child by declaring that he himself is collateral on the loan. Akiko’s mother is hospitalised with TB – the misfortune that’s had her father reduced to this shaming state of affairs. To make matters worse it’s not as if she can even tell her mother why her father hasn’t visited for a couple of weeks or explain why the nurse was complaining that their insurance has expired. Her father is also in poor health and likely will not cope very well with remaining in prison hence why she (briefly) considers becoming someone’s mistress or going on a date with a dangerous and unpleasant man to get the money to bail him out.

In any other seishun eiga this situation would be a recipe for a disaster, but somehow it rescues itself from the brink of despair and becomes almost more of salty rom-com than anything else. After the initial cute sea-side and roller skating date, there are crossed wires, mislaid messages and a last minute dash to work out a forgotten address but the film never loses its youthful energy and guileless wit. The world outside might be cruel, but in here it’s just normal, and if a boy and a girl want to blow some time at the races or the beach, who can blame them. They’re young, they’re kind of unhappy but they’ll figure it out and probably be OK which is a lot more than you can say for the usual protagonists of these kinds of film.

Kisses doesn’t have the searing, angry eyes of Masumura’s later work. Yes there is dissatisfaction with the world as it is, but also hope and acceptance, rather than an attempt at rebellion. Neither of the two young lovers is trying to change the world. Forced to be older than they are, both are savvy and realistic but not quite old enough to be fearful or self-centred. Full of youthful nonchalance, Kisses is a tale of innocent romance which is only improved by its layer of ironic whimsy.

Kisses is available with English subtitles on R2 UK DVD from Yume Pictures.

The only (short) clip I could find only has Russian subs…but it’s of a song which is very pretty.

The automobile business is a high stakes game. Do you want to play faster, shinier and sleeker, or safer, family friendly and reliable? Family cars are the best sellers – everyone one wants something that’s reliable for getting to work every morning, getting the grocery shopping done and that you won’t worry about taking your kids to the park in. However, it’s the 1960s and lifestyles are shifting, men (in particular) are marrying later and they want to have fun before they do – hence having quite a lot of disposable income they can blow on a flashy two-seater sports car with no wife to complain about it. Tiger have just finished a new prototype called the Pioneer they plan to launch as a revolution in commercial sports cars which is super speedy but with the convenience of an everyday sedan. However, the Yamato company are also set to launch a new car and it keeps looking suspiciously like the Pioneer – does Tiger have a mole?

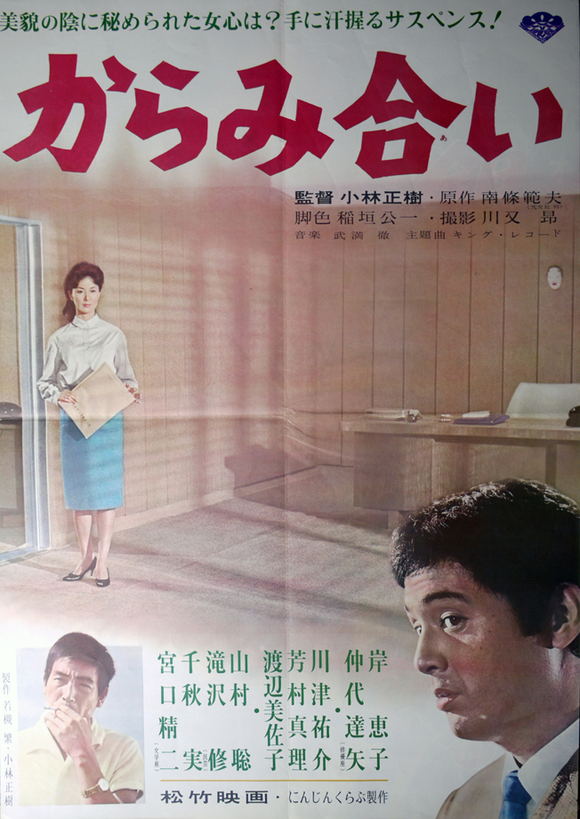

The automobile business is a high stakes game. Do you want to play faster, shinier and sleeker, or safer, family friendly and reliable? Family cars are the best sellers – everyone one wants something that’s reliable for getting to work every morning, getting the grocery shopping done and that you won’t worry about taking your kids to the park in. However, it’s the 1960s and lifestyles are shifting, men (in particular) are marrying later and they want to have fun before they do – hence having quite a lot of disposable income they can blow on a flashy two-seater sports car with no wife to complain about it. Tiger have just finished a new prototype called the Pioneer they plan to launch as a revolution in commercial sports cars which is super speedy but with the convenience of an everyday sedan. However, the Yamato company are also set to launch a new car and it keeps looking suspiciously like the Pioneer – does Tiger have a mole? Kobayashi’s first film after completing his magnum opus, The Human Condition trilogy, The Inheritance (からみ合い, Karami-ai) returns him to contemporary Japan where, once again, he finds only greed and betrayal. With all the trappings of a noir thriller mixed with a middle class melodrama of unhappy marriages and wasted lives, The Inheritance is yet another exposé of the futility of lusting after material wealth.

Kobayashi’s first film after completing his magnum opus, The Human Condition trilogy, The Inheritance (からみ合い, Karami-ai) returns him to contemporary Japan where, once again, he finds only greed and betrayal. With all the trappings of a noir thriller mixed with a middle class melodrama of unhappy marriages and wasted lives, The Inheritance is yet another exposé of the futility of lusting after material wealth. Having taken avant-garde story telling to its zenith in

Having taken avant-garde story telling to its zenith in  The second film contained within Arrow’s Kiju Yoshida boxset is perhaps his least accessible. Ostensibly, Heroic Purgatory (煉獄エロイカ, Rengoku Eroika) is an examination of leftist politics in the years surrounding the renewal of the hugely controversial mutual security pact between Japan and America. However, it quickly disregards any kind of narrative sense as time periods blur so finely as to leave us with no objective “now” to belong to and characters switch identities with no warning or discernible reason. Yoshida is not really after objective truth here – there is no truth in cinema, film lies repeatedly until it finally exposes the truth.

The second film contained within Arrow’s Kiju Yoshida boxset is perhaps his least accessible. Ostensibly, Heroic Purgatory (煉獄エロイカ, Rengoku Eroika) is an examination of leftist politics in the years surrounding the renewal of the hugely controversial mutual security pact between Japan and America. However, it quickly disregards any kind of narrative sense as time periods blur so finely as to leave us with no objective “now” to belong to and characters switch identities with no warning or discernible reason. Yoshida is not really after objective truth here – there is no truth in cinema, film lies repeatedly until it finally exposes the truth. One of the foremost avant-garde filmmakers of the New Wave era (though he detested this term which, in fairness, is a retrospective and often arbitrary label), Kiju (Yoshishige) Yoshida has remained largely unseen in the West. Some of this is his own fault – fiercely independent, Yoshida nevertheless found himself working with ATG after leaving Shochiku but the relationship was an unusual one and often far from easy. All but the latest film in Arrow’s Kiju Yoshida boxset,

One of the foremost avant-garde filmmakers of the New Wave era (though he detested this term which, in fairness, is a retrospective and often arbitrary label), Kiju (Yoshishige) Yoshida has remained largely unseen in the West. Some of this is his own fault – fiercely independent, Yoshida nevertheless found himself working with ATG after leaving Shochiku but the relationship was an unusual one and often far from easy. All but the latest film in Arrow’s Kiju Yoshida boxset,