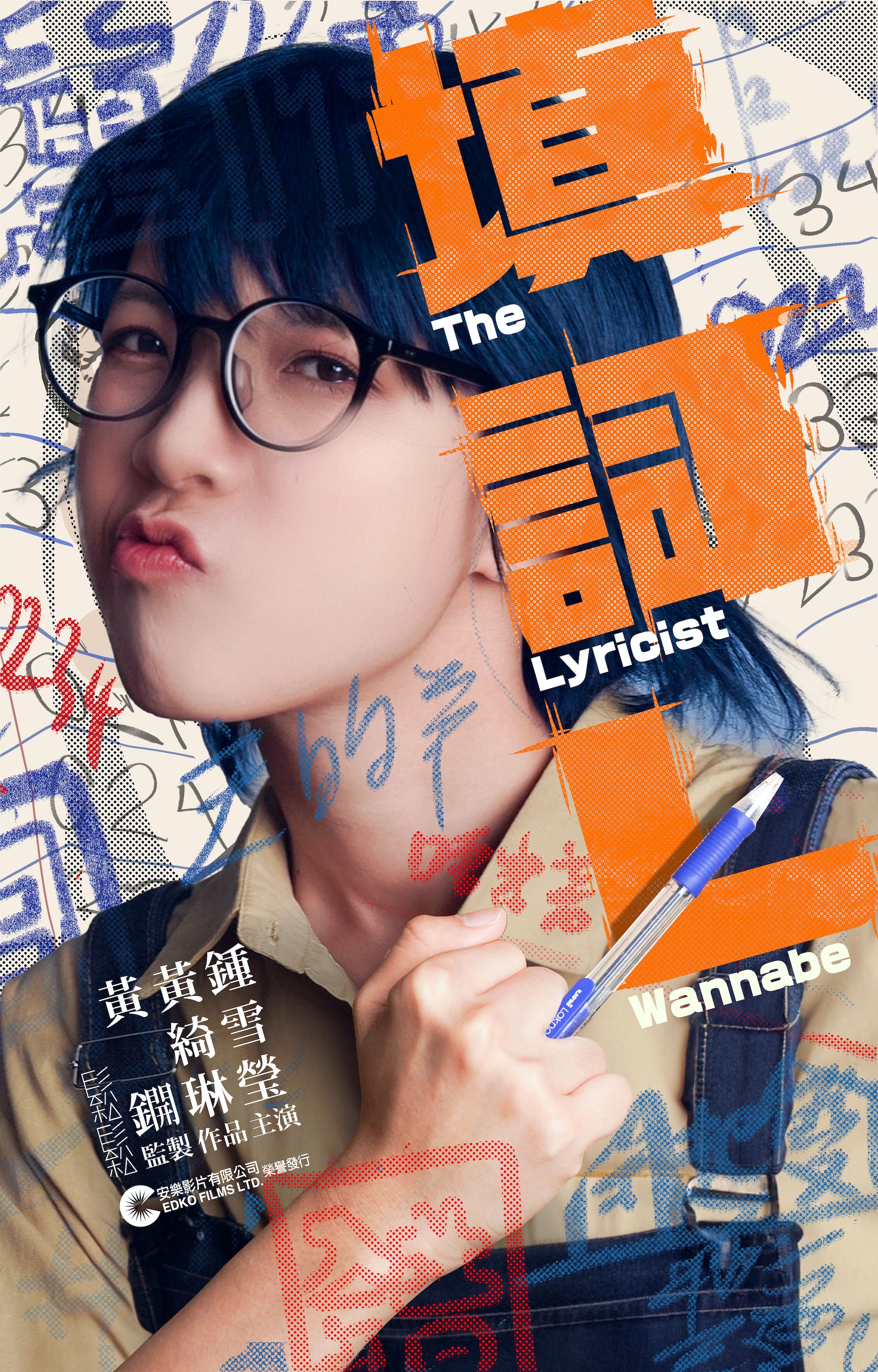

Sometimes a dream might have come true only we never really noticed. In Norris Wong’s autobiographically inspired drama The Wannabe Lyricist (填詞L), a young woman battles her way towards becoming a Cantopop songwriter yet perhaps she already is one by virtue of her constant act of lyric writing. What she craves is the validation of having a song published, yet experiences setbacks at every step of the way that encourage her to doubt her talent or the right to continue chasing her dreams.

At a particularly low point after being taken on by a music producer to work with a spoilt influencer who’s getting studio time as some kind of favour, Sze (Chung Suet Ying) is told that her lyrics are no good and that after struggling so hard for six years perhaps she ought to take the hint and accept she isn’t suited to this line of work. It’s an act of intense cruelty, though one in part motivated by a well-meaning faux pas. In her excitement, she told the influencer she’d write lyrics for her album for free just to be published, but the palpable sense of desperation seems to have put the influencer off unable to have confidence in the work that Sze herself has devalued.

She encounters something similar during a partnership with an aspiring pop star who says he likes her lyrics but then drops the bombshell that he plans to sing in Mandarin because it’s a bigger audience. Ironically, on a trip to Taipei to sell his album she’s told that his accent is no good for the local market and while they like the song she worked on she later realises that they hired another lyricist for “real” release without even telling her. What’s more, tones don’t matter while singing in Mandarin whereas lyric writing in Cantonese is a painstaking process of trying to ensure that the tone of the word fits the melody. Aside from its political implications, not only does the pop star’s arbitrary decision to just sing it Mandarin ruin the lyrical flow she spent so long perfecting but entirely disrespects her work.

After deciding to take a break from trying to make it in music, Sze gets a job working at a ridesharing app startup where she’s roped in to create a jingle but once again her hopes are dashed when the business strays into a legal grey area and several of the drivers are arrested. While the app’s creator silently cries in his office, his female colleague ponders going somewhere else, “anywhere that doesn’t punish dreamers” which seems like a nod not only towards an oppressive capitalism that values only marketability but equally the increasingly oppressive atmosphere of the nation’s political realities. In a way this is what Sze ends up doing too, putting geographical distance between herself and the failure of her dreams by returning to the land which as the farmer says never lies to you, you reap what sow.

Yet for all her drive and perseverance there are others who view Sze’s obsession with her dreams as selfish and self-involved complaining that she rarely considers the feelings of others and neither notices nor cares if she may have hurt or inconvenienced them. She’s told that her lyrics are hollow because she lacks life experience but also is incapable of empathising and cannot see anything outside of her quest to become a lyricist. She watches other people move on, her brother getting married, friends enjoying career success etc while she’s still stuck looking for her big break only for something to go wrong just as everything was about to go right.

Wong signals the playful qualities of her fantasies though use of onscreen illustrations and even a karaoke-style video along with the nostalgic quality of the early 2000s setting of Sze’s schooldays with its MSN messenger and ICQ. Sze may be “dragged along by the melody” in more ways than one as she tries to make peace with her dreams and her future and find some way of living in harmony with the rhythms of the world around her but eventually comes to realise that she was a lyricist all along no matter what anyone else might have tried to convince her she was.

The Lyricist Wannabe screened as part of this year’s Osaka Asian Film Festival and opens in UK cinemas 15th March courtesy of Cine Asia.

Original trailer (Traditional Chinese / English subtitles)