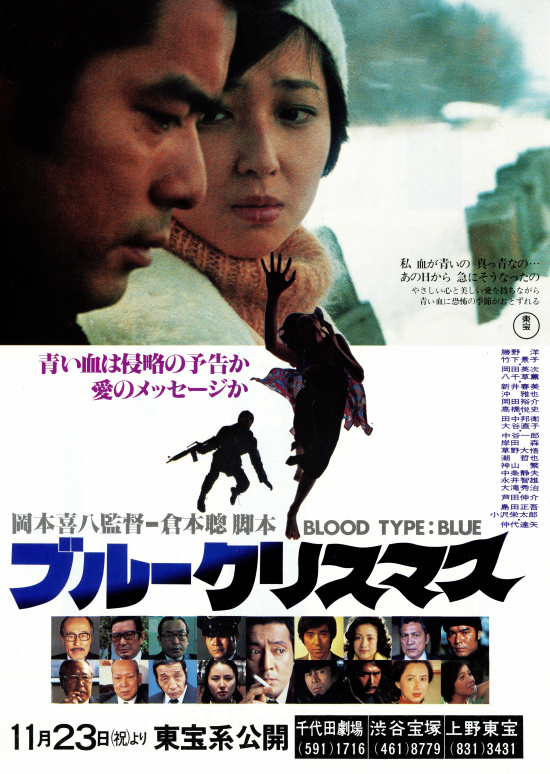

The Christmas movie has fallen out of fashion of late as genial seasonally themed romantic comedies have given way to sci-fi or fantasy blockbusters. Perhaps surprisingly seeing as Christmas in Japan is more akin to Valentine’s Day, the phenomenon has never really taken hold meaning there are a shortage of date worthy movies designed for the festive season. If you were hoping Blue Christmas (ブルークリスマス) might plug this gap with some romantic melodrama, be prepared to find your heart breaking in an entirely different way because this Kichachi Okamoto adaptation of a So Kuramoto novel is a bleak ‘70s conspiracy thriller guaranteed to kill that festive spirit stone dead.

The Christmas movie has fallen out of fashion of late as genial seasonally themed romantic comedies have given way to sci-fi or fantasy blockbusters. Perhaps surprisingly seeing as Christmas in Japan is more akin to Valentine’s Day, the phenomenon has never really taken hold meaning there are a shortage of date worthy movies designed for the festive season. If you were hoping Blue Christmas (ブルークリスマス) might plug this gap with some romantic melodrama, be prepared to find your heart breaking in an entirely different way because this Kichachi Okamoto adaptation of a So Kuramoto novel is a bleak ‘70s conspiracy thriller guaranteed to kill that festive spirit stone dead.

A Japanese scientist disgraces himself and his country at an international conference by affirming his belief in aliens only to mysteriously “disappear” on the way back to his hotel. Intrepid reporter Minami (Tatsuya Nakadai) gets onto the case after meeting with a friend to cover the upcoming release of the next big hit – Blue Christmas by The Humanoids. His friend has been having an affair with the network’s big star but something strange happened recently – she cut her finger and her blood was blue. Apparently, hers is not an isolated case and some are linking the appearance of these “Blue Bloods” to the recent spate of UFO sightings. Though there is nothing to suggest there is anything particularly dangerous about the blue blood phenomenon, international tensions are rising and “solutions” are being sought.

A second strand emerges in the person of government agent, Oki (Hiroshi Katsuno), who has fallen in love with the assistant at his local barbers, Saeko (Keiko Takeshita). Responsible for carrying out assassinations and other nefarious deeds for the bad guys, Oki’s loyalty is shaken when a fellow officer and later the woman he loves are also discovered to be carriers of the dreaded blue blood.

Okamoto lays the parallels on a little thick at times with stock footage of the rise of Nazism and its desire to rid the world of “bad blood”. Sadly, times have not changed all that much and the Blue Bloods incite nothing but fear within political circles, some believing they’re sleeper agents for an alien invasion or somehow intended to overthrow the global world order. Before long special measures have been enforced requiring all citizens to submit to mandatory blood testing. The general population is kept in the dark regarding the extent of the “threat” as well as what “procedures” are in place to counter it, but anti Blue Blood sentiment is on the rise even if the students are on hand to launch the counter protest in protection of their blue blooded brethren, unfairly demonised by the state.

The “procedures” involve mass deportations to concentration camps in Siberia in which those with blue blood are interrogated, tortured, experimented on and finally lobotomised. This is an international operation with people from all over the world delivered by their own governments in full cognisance of the treatment they will be receiving and all with no concrete evidence of any kind of threat posed by the simple colouring of their blood (not that “genuine threat” would ever be enough to excuse such vile and inhuman treatment). In the end, the facts do not matter. The government has a big plan in motion for the holiday season in which they will stage and defeat a coup laid at the feet of the Blue Blood “resistance”, ending public opposition to their anti-Blue Blood agenda once and for all.

Aside from the peaceful protest against the mandatory blood testing and subsequent discrimination, the main opposition to the anti-Blue Blood rhetoric comes from the ironically titled The Humanoids with the ever present Blue Christmas theme song, and the best efforts of Minami as he attempts to track down the missing scientist and uncover the conspiracy. This takes him around the world – firstly to America where he employs the somewhat inefficient technique of simply asking random people in the street if they’ve seen him. Laughed out of government buildings after trying to make serious enquires, Minami’s last hope lies in a dodgy part of town where no one would even try to look, but he does at least get some answers. Unfortunately, the information he receives is inconvenient to everyone, gets him fired from the investigation, and eventually earns him a transfer to Paris.

In keeping with many a ‘70s political thriller, Blue Christmas is bleaker than bleak, displaying little of Okamoto’s trademark wit in its sorry tale of irrational fear manipulated by the unscrupulous. In the end, blue blood mingles with red in the Christmas snow as the bad guys win and the world looks set to continue on a course of hate and violence with a large fleet of UFOs apparently also on the way bearing uncertain intentions. Legend has it Okamoto was reluctant to take on Blue Christmas with its excessive dialogue and multiple locations. He had a point, the heavy exposition and less successful foreign excursions overshadow the major themes but even so Blue Christmas has, unfortunately, become topical once again. Imperfect and cynical if gleefully ironic in its frequent juxtapositions of Jingle Bells and genocide, Blue Christmas’ time has come as its central message is no less needed than it was in 1978 – those bleak political conspiracy thrillers you like are about to come back in style.

Original trailer (No subtitles)

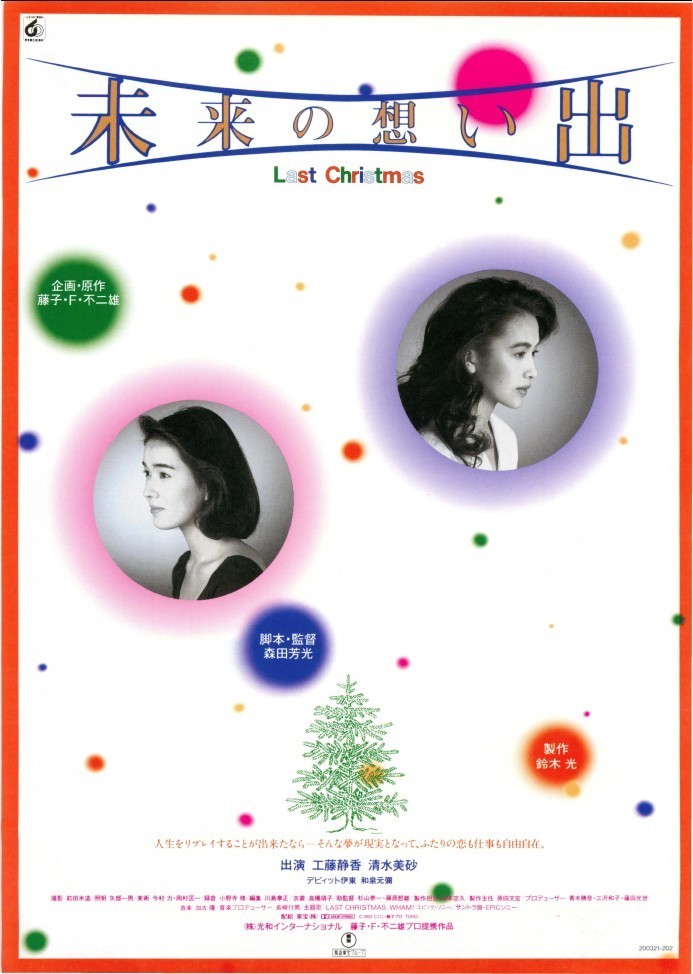

Based on the contemporary manga by the legendary Fujiko F. Fujio (Doraemon), Future Memories: Last Christmas (未来の想い出 Last Christmas, Mirai no Omoide: Last Christmas) is neither quiet as science fiction or romantically focussed as the title suggests yet perhaps reflects the mood of its 1992 release in which a generation of young people most probably would also have liked to travel back in time ten years just like the film’s heroines. Another up to the minute effort from the prolific Yoshimitsu Morita, Future Memories: Last Christmas is among his most inconsequential works, displaying much less of his experimental tinkering or stylistic variations, but is, perhaps a guide its traumatic, post-bubble era.

Based on the contemporary manga by the legendary Fujiko F. Fujio (Doraemon), Future Memories: Last Christmas (未来の想い出 Last Christmas, Mirai no Omoide: Last Christmas) is neither quiet as science fiction or romantically focussed as the title suggests yet perhaps reflects the mood of its 1992 release in which a generation of young people most probably would also have liked to travel back in time ten years just like the film’s heroines. Another up to the minute effort from the prolific Yoshimitsu Morita, Future Memories: Last Christmas is among his most inconsequential works, displaying much less of his experimental tinkering or stylistic variations, but is, perhaps a guide its traumatic, post-bubble era.