In the closing moments of Zhang Yimou’s Hero (英雄, Yīngxióng), what we see is an empty space. The outline of a person surrounded by arrows, or perhaps the doorway they protected with their body that nevertheless remains closed. On its initial release, Zhang’s film received criticism for what some saw as an overt defence of authoritarianism. After all, what we may come to understand is that the hero of the title is the Qin emperor (Chen Daoming), the founder of the modern China, but also in historical record a brutal tyrant whose tyranny is therefore justified in the name of peace, just as contemporary authoritarianism is justified in the name or safety and order.

This reading is only reinforced by the demeanour of Qin himself who condemns the nameless “hero” to death because he has chosen authority and this is what authority demands. No forgiveness, no compassion, only brutality and an iron first. Yet he cries because he is a compassionate man and understands the sacrifice he is asking his remorseful assassin to make. He does not do it because he is cruel or out of vengeance or anger, but because he believes it necessary to ensure peace for “all under heaven”. Now we may find ourselves asking again if the assassin is the hero after all because he willingly submits himself to and sacrifices himself for a tyrannous authority because he believes it to be the best and only choice that he can make for the wider society.

Nevertheless, there is something chilling in the vision of a thousand arrows flying toward one man who does not flinch while the man who ordered them sent appears to shake with his own power. The soldiers retreat, and the king is left alone, dwarfed by the immense architecture of the palace and the blood-red calligraphy of the character for sword reimagined by another potential hero whose name echoes his final conviction that in the end the apotheosis of the swordsman lies in the realisation that there is no sword. It’s this that leads him to abandon is own desire to assassinate the king and submit himself to a greater authority in the name of peace. In the end what he rejects is the tyranny of the sword itself, yet the king is also an embodiment of that tyranny because his authority is only possible through terrifying violence.

In this way, the assassin, ironically named “Nameless” (Jet Li), may stand in for the everyman refusing to bow to the authority of a corrupt king who cares only for power. In one of the many tales he tells, Nameless remarks that he fought with the first of Qin’s three assassins in his mind and it’s true enough that what passes between the two men is a duel of words which is eventually won by the king. Qin tells Nameless of his desire to increase his influence beyond the other six kingdoms of Warring States China and create an empire that encompasses “all under heaven”, but Nameless later cautions him to remember those who gave their lives for the highest ideal, peace, and refrain from further killing. The closing title card is displayed over the Great Wall, making plain that Qin did in fact stop after conquering the six other kingdoms to unite all of China while building the wall to protect his citizens from “northern tribes,” or perhaps competing imperialists.

But walls keep people in as well as out and are in fact another facet of the king’s tyranny and a symbol of enduring authoritarianism. The problem is that it isn’t tyranny or authoritarianism that any of the assassins oppose for they are driven only by hate and vengeance and have no greater ideology or vision for the future. The argument is that peace under the iron fist of Qin is better than the chaotic freedom of the Warring States society, yet what we’re left with is nihilism. The love between assassins Flying Snow (Maggie Cheung Man-yuk) and Broken Sword (Tony Leung Chiu-wai ) is disrupted in each of the tales Nameless relates of them, firstly by romantic jealously and then secondly ideological divide. The conclusion that Broken Sword comes to is that they must not resist, but Flying Snow cannot live without recrimination with the past and the sealing of its tragic legacy. Her revolution fails, and as such “all under heaven” there is only death and only in death is freedom to be found.

The sense that these assassins are already dead is echoed in the choice of white for the final sequence of the film. Zhang frames each of his sequences in vibrant colour, the red of the first tale in which the lovers are destroyed by a supposed love triangle, the blue of the second in which tragedy and sacrifice do not so much destroy as deify it, the green of the penultimate in which jade curtains billow and fall inside the imperial palace, and finally the cold white of death in which the lovers eventually find their home leaving their surrogate child alone in a windy desert of futility. Yet each of these sequences is filled with an intense beauty and the romanticism found in classic wuxia. What remains in the mind is the balletic fight between the tragic heroine Flying Snow and the orphaned pupil Fading Moon (Zhang Ziyi) in an autumnal forest that’s suddenly drenched in red, or feet dancing across the water, an image of an idealised past and lost love among wandering ghosts with no home to go to. Here there are no heroes, only lonely souls and frustrated ideals.

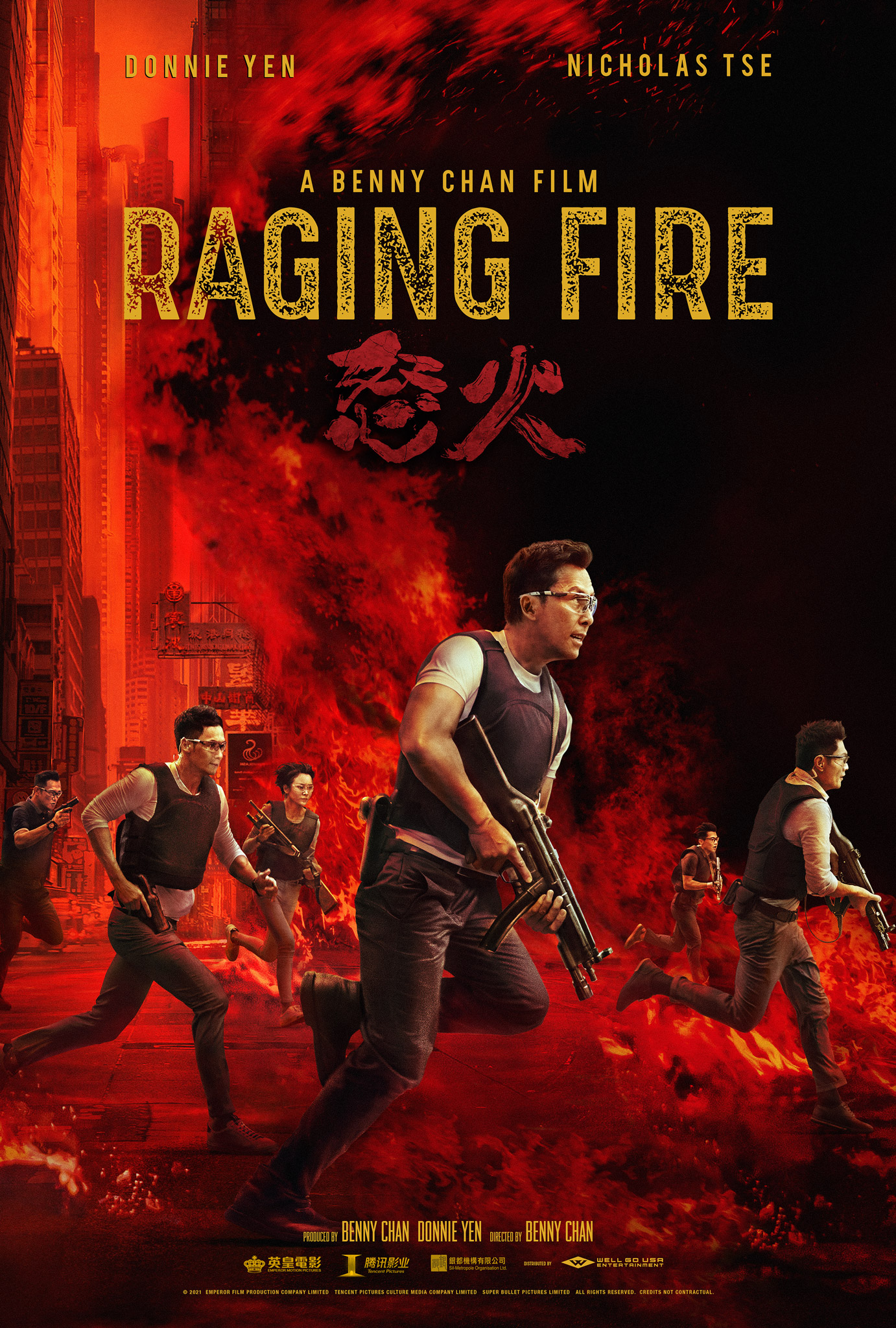

Kung fu movies – they don’t make ‘em like they used to, except when they do. Kung Fu Killer (一個人的武林, AKA Kung Fu Jungle) is equal parts homage and farewell as its ageing star, Donnie Yen, prepares to graduate to the role of master rather than rebellious pupil. What it also is, is a battle for the soul of kung fu. Just how “martial” should a martial art be? Is it, as our antagonist tells us, worthless with no death involved or will our hero prove the spiritual and mental benefits which come with its rigorous training and inner centring transcend its original purpose? Of course most of this is just posturing in the background of a lovingly old fashioned fight fest complete with a non-sensical plot structure motivated by increasingly elaborate set pieces.

Kung fu movies – they don’t make ‘em like they used to, except when they do. Kung Fu Killer (一個人的武林, AKA Kung Fu Jungle) is equal parts homage and farewell as its ageing star, Donnie Yen, prepares to graduate to the role of master rather than rebellious pupil. What it also is, is a battle for the soul of kung fu. Just how “martial” should a martial art be? Is it, as our antagonist tells us, worthless with no death involved or will our hero prove the spiritual and mental benefits which come with its rigorous training and inner centring transcend its original purpose? Of course most of this is just posturing in the background of a lovingly old fashioned fight fest complete with a non-sensical plot structure motivated by increasingly elaborate set pieces.