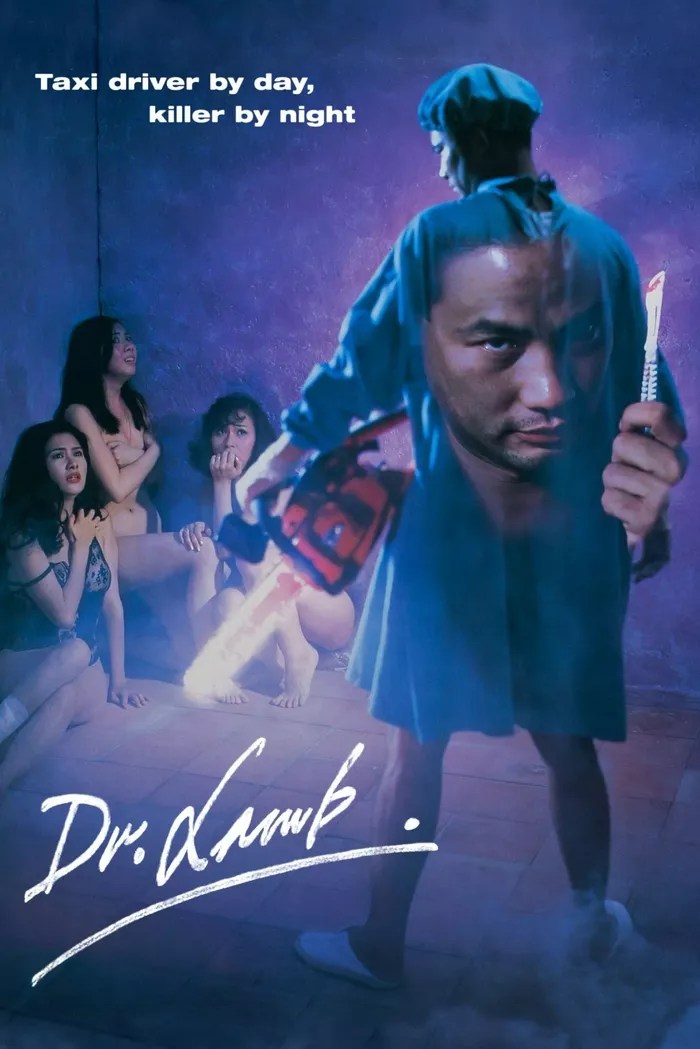

“Every good man should get revenge” the young protagonist of Danny Lee Sau-Yin and Billy Tang Hin-Shing’s depraved Cat III shocker Dr. Lamb (羔羊醫生) is told though as will become apparent, he is not a good man and if his heinous crimes are born of vengeance the target may remain indistinct. Long available only in a censored version which perhaps helped to create its gruesome reputation, the film like others in the early ‘90s Cat III boom is based on a real life case, that of taxi driver Lam Kor-wan who murdered four female passengers before being caught by police when an assistant at a photo shop alerted them to the disturbing quality of the negatives he had brought in to be developed.

As such, the film is not a procedural. It begins with the arrest of a man here called Lin Gwao-yu (Simon Yam Tat-Wah) who claims the negatives are not his and that he brought them in on behalf of a friend named Chang (which is also coincidentally the name of the half-brother he continues to resent). On investigating the flat where he lives with his father, half-siblings, and niece, the police realise that Gwao-yu is in indeed a serial killer and the rest of the film is divided into a series of flashbacks as they try to convince him to confess and reveal how and why he committed these crimes the last of which he actually videoed himself doing.

Nevertheless, the police themselves are depicted not quite as bumbling but certainly not much better than the criminals they prosecute in their own lust for violence, savagely beating Gwao-yu who refuses to speak in order to force him to confess. Fat Bing (Kent Cheng Jak-Si) is portrayed as a particularly bad example, encouraging the other cops to play cards rather than focus on their stakeout of the photo shop almost allowing Gwao-yu to escape and then titillated by the more normal pinups and glamour shots pinned to Gwao-yu’s wardrobe as well as some of the less normal ones before realising that the women in them are dead. There is some original controversy over whether they should be investigating at all given that taking weird pictures of nude women is not in itself illegal while the misogynistic attitudes of the police are carried over onto one of their own officers who is forced to play the part of the victim during a re-enactment and is later struck by a stray body part as a result of Fat Bing’s crime scene incompetence. One of the murders even takes place directly outside a police box where the victim had tried to ask for help but got no reply.

Pressed for a reason for his crimes Gwao-yu offers only that all but the last of his victims were bad women who deserved die, each in a repeated motif fatalistically colliding with his cab and crawling inside having had too much to drink. Flashbacks to his childhood place the blame on his wicked step-mother’s rejection along with that of his siblings while his father alone defends him if somewhat indifferently, describing him as merely “curious” on catching Gwao-yu voyeuristically spying on he and his wife having sex and disowning him only on discovering that he has also been abusing his niece who is strangely the only member of the family who seems to be fond of him. Yet it’s also this problematically incestuous living environment that has facilitated his crimes. Gwao-yu takes the bodies home to play with and dismember having the house to himself during the day because he works nights while continuing to share a pair of bunk beds with the brother he hates at the age of 28 either unwilling or unable to get a place of his own on a taxi driver’s earnings. Aside from his brother noticing a strange smell, the family who all think him weird anyway apparently remain oblivious to Gwao-yu’s crimes despite the jars containing body parts he keeps in a locked cupboard along with disturbing photographs of his dark deeds. Nevertheless it’s their police-sanctioned beating of him which eventually provokes his confessions.

Set off by rainy nights, Gwao-yu twitches, gurns, and howls like a dog leering at his victims like a predatory wolf. In the police interrogation scenes he continues with his strange, dancelike movements as if in a trance reliving his crimes. The truth is that the police had not really investigated the disappearances of the women he killed, had no clue a serial killer was operating, and would not have caught Gwao-yu if it were not for his own lack of interest in not being caught in taking the photos to be developed publicly despite claiming to have the ability to have simply developed them himself while videoing his brutal treatment of one victim’s body and his disturbing “wedding night” with another. A final scene of Inspector Lee visiting Gwao-yu in prison visually references Clarice’s first visit to Dr. Lecter in Silence of the Lambs which might go someway to explaining the title which is otherwise perhaps ironic in Gwao-yu’s ritualistic use of a scalpel and specimen jars. In any case for all its lurid, disturbing content the film has a strange beauty in its atmospheric capture of a neon-lit Hong Kong stalked as it is by an almost palpable evil.

Dr. Lamb screened as part of this year’s Fantasia International Film Festival and is available on blu-ray in the US courtesy of Unearthed Films.

Original trailer (no subtitles)