Desire and desperation bubble to the surface at a small hotel making preparations for a wedding in Takuya Misawa’s Chigasaki Story (3泊4日、5時の鐘, 3-paku 4-ka, 5-ji no kane). Though the English-language title may recall Ozu who wrote several of his most highly regarded films while staying at the inn, Misawa pays him only cheerful homage with a series of pillow shots apparently added only as an afterthought while his true inspiration seems to lie in the breezy Rohmerism that has come to dominate a certain strain of Japanese indie cinema over the last decade or so.

Accordingly the tale is set in the small seaside town of Chigasaki and most particularly at the 115-year-old Chigasaki Inn to which former airline ground crew Risa has recently returned following her marriage to a filmmaker named George whom she met in the course of her work. The couple have already held the ceremony and enjoyed a honeymoon in Hawaii but are now holding a celebratory party for their friends and family in Japan. Meanwhile the inn is also host to a contingent of university students from the same department in which local boy and part-time worker Tomoharu is studying archeology.

Somewhat meek and mild-mannered, Tomoharu takes his job incredibly seriously and is generally found running around on errands for guests or else cleaning up but his presence becomes a disruptive factor caught between the two groups of visitors instantly captivated as he is on the arrival of Karin, a young and pretty former co-worker of Risa’s who has arrived with the comparatively uptight Miki who has missed nothing in this exchange and is already frustrated by her friend’s wanton behaviour. Miki undeniably has a point when she criticises Karin for putting Tomoharu in an awkward position by inappropriately flirting with him at his job especially as he seems shy and easily embarrassed, but in turn is perhaps also jealous on a personal level intensely irritated when she blows off a plan to visit an aquarium to hang out on the beach with Tomoharu at stupid o’clock in the morning.

The row only highlights the differences between the mismatched friends though the tables are turned when Miki realises that the students are from her old university and in fact led by her former professor with whom she begins to grow close much to Karin’s consternation. Reverting to her student persona, “workaholic” Miki becomes carefree and uninhibited at once doling out pieces of sisterly advice to the younger women and imposing her company on the students by joining in on their field trip. Her behaviour may in a sense reflect her dissatisfaction with her life as she contends with overbearing bosses having taken over Risa’s role while complaining about Karin’s fecklessness at work and otherwise seemingly jealous of their ill-defined friendship. Risa meanwhile may also be harbouring a degree of doubt in her decision to quit her job, get married, and return to run the family inn especially as her new husband is off working until the day of the party and like everyone else there isn’t really anyone with whom she can share those feelings honestly leading to an unwise if possibility long-term act of rebellion against a potentially stultifying existence that places her at further odds with the already on edge Miki.

Caught between the women Tomoharu also has a more age-appropriate suitor in an earnest young woman from his class, Ayako, who likes him because of his tendency to care for others while getting on quietly with his work. Attempts to communicate culminate in a lengthy game of ping pong as the angry little balls of truth are batted back and fore across the table until a third player enters the scene and disrupts the flow. Tomoharu had said that his work of piecing ancient bowls back together was different from a jigsaw puzzle because you don’t know what shape it’s supposed to be until it’s finished, which might in a way explain these intersecting relationships as they run through and across each other but ultimately ending up in the place that they’re supposed to be culminating in a wedding party which is either the calm after the storm, an intense act of hypocrisy, or something between the two.

Trailer (no subtitles)

When everything goes wrong you go home, but Yuriko, the protagonist of Yuki Tanada’s adaptation of Yuki Ibuki’s novel might feel justified in wondering if she’s made a series of huge mistakes considering the strange situation she now finds herself in. Far from the schmaltzy cooking movie the title might suggest, Mourning Recipe (四十九日のレシピ, Shijuukunichi no Recipe) is a trail of breadcrumbs left by the recently deceased family matriarch, still thinking of others before herself as she tries to help everyone move on after she is no longer there to guide them. Approaching the often difficult circumstances with her characteristic warmth and compassion, Tanada takes what could have become a trite treatise on the healing power of grief into a nuanced character study as each of the left behind now has to seek their own path in deciding how to live the rest of their lives.

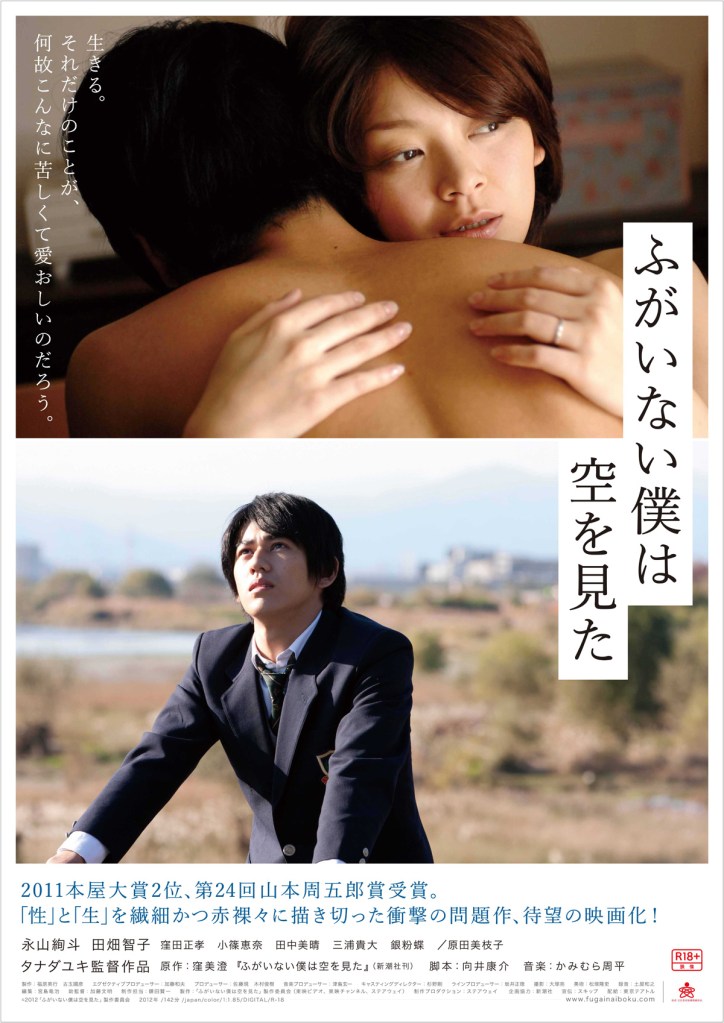

When everything goes wrong you go home, but Yuriko, the protagonist of Yuki Tanada’s adaptation of Yuki Ibuki’s novel might feel justified in wondering if she’s made a series of huge mistakes considering the strange situation she now finds herself in. Far from the schmaltzy cooking movie the title might suggest, Mourning Recipe (四十九日のレシピ, Shijuukunichi no Recipe) is a trail of breadcrumbs left by the recently deceased family matriarch, still thinking of others before herself as she tries to help everyone move on after she is no longer there to guide them. Approaching the often difficult circumstances with her characteristic warmth and compassion, Tanada takes what could have become a trite treatise on the healing power of grief into a nuanced character study as each of the left behind now has to seek their own path in deciding how to live the rest of their lives. The work of director Yuki Tanada has had a predominant focus on the stories of independent young women but The Cowards Who Looked to the Sky sees her shift focus slightly as the troubled relationship between a middle aged housewife who escapes her humdrum life through cosplay and an ordinary high school boy takes centre stage. Based on the novel of the same name by Misumi Kubo, The Cowards Who Looked to the Sky (ふがいない僕は空を見た, Fugainai Boku wa Sora wo Mita) also tackles the difficult themes of social stigma, the power of rumour, teenage poverty, elder care, childbirth and even pedophilia which is, to be frank, a little too much to be going on with.

The work of director Yuki Tanada has had a predominant focus on the stories of independent young women but The Cowards Who Looked to the Sky sees her shift focus slightly as the troubled relationship between a middle aged housewife who escapes her humdrum life through cosplay and an ordinary high school boy takes centre stage. Based on the novel of the same name by Misumi Kubo, The Cowards Who Looked to the Sky (ふがいない僕は空を見た, Fugainai Boku wa Sora wo Mita) also tackles the difficult themes of social stigma, the power of rumour, teenage poverty, elder care, childbirth and even pedophilia which is, to be frank, a little too much to be going on with.