A young woman returns home at a moment of crisis, but finds herself with only more questions in an attempt to understand her mother and her decision to leave Nagasaki for the UK 30 years previously in Kei Ishikawa’s adaptation of Kazuo Ishiguro’s debut novel, A Pale View of Hills (遠い山なみの光, Toi yama-nami no Hikari). Set alternately in 1952 and 1982, the film positions the Greenham Common anti-nuclear protests as a point of connection between the two nations and the reason that Niki (Camilla Aiko) is currently so interested in her mother’s story seeing as there’s increased interest surrounding the atomic bomb, even if her editor keeps asking her about “Hiroshima”.

Another reason for Niki’s sudden return is that the editor is a married man Niki has been having an affair with. It seems she’s made a significant investment in the relationship by dropping out of university to work as a reporter, but despite saying he would, he has not left his wife and Niki suspects she may now be pregnant. All of which encourages her to investigate the relationship she has with her mother, Etsuko (Yo Yoshida / Suzu Hirose), and her late sister Keiko with whom she did not seem to get on, through tracing back her Japanese roots and trying to understand her familial history.

But what Etsuko, who is abruptly selling the family home, tells her is confusing and indistinct. Much of Etsuko’s story doesn’t line up, and we understand in part why later, but it seems almost as if the lacunas and contradictions are intentional and designed to hint at the ways we paper over cracks in our identities or create new mythologies for ourselves in an attempt to escape the traumatic past. Etsuko found a more literal escape in coming to the UK, but there’s something a little poignant about the way she says she thought there’d be more opportunities here and that Keiko would have had the chance to be anything she wanted which Japan would have denied her. Later she suggests that she always knew the UK wouldn’t be good for Keiko, but she came anyway.

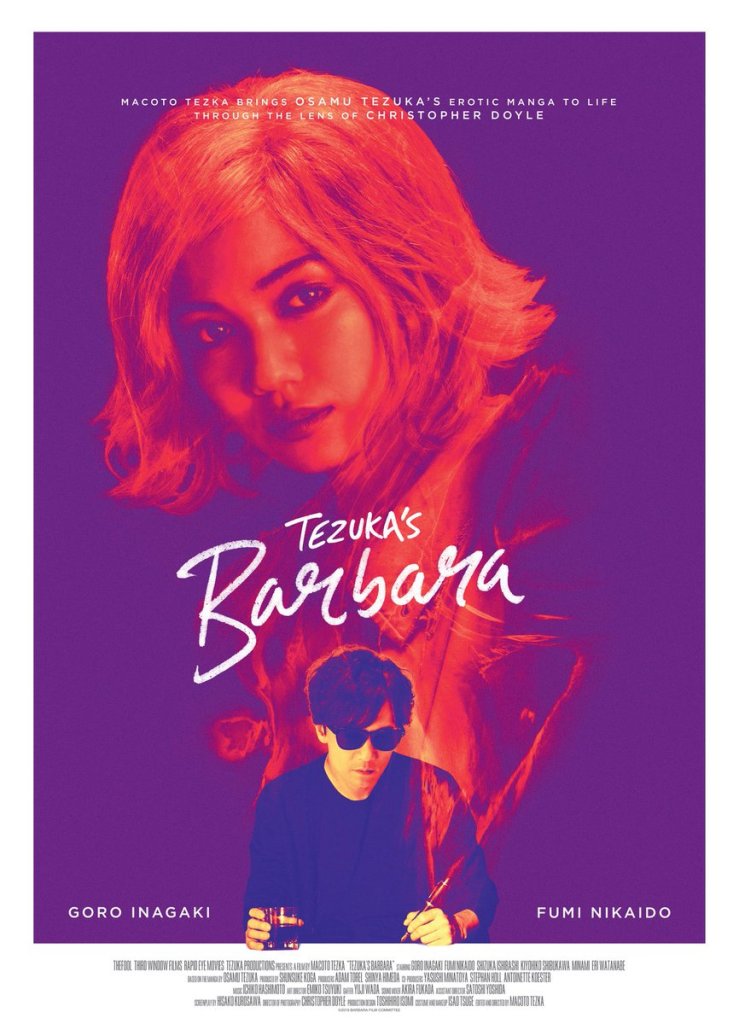

Now she’s selling the house, literally unpacking the past, Etsuko has begun dreaming about a woman she knew, Sachiko (Fumi Nikaido), and her daughter, Mariko, who lived near her in Nagasaki when she was pregnant with Keiko. Whereas Etsuko and her salaryman husband Jiro (Kohei Matsushita) live in a flat on a “danchi”, aspirational post-war housing estates for young families, Sachiko lives in a rundown shack across the way where the neighbours gossip about her for entertaining American soldiers who are still in the country post-Occupation because of the Korean War which is also what’s fuelling the economic recovery. Sachiko has met a man called Frank who says he’ll take her to America, but she doesn’t really believe him.

On the one level, it seems that Etsuko and Sachiko are mirror images of each other yet they are in other ways alike, while their stories share several details in common. What unites them is that they both experienced the aftermath of the bomb, though Etsuko has been careful not to disclose the extent of her exposure and is now fearful of what effect it may have on the baby along with on her relationship with her husband who appears to share some of the prevailing social prejudice against those who were exposed to radiation. Jiro, meanwhile, is a distant workaholic who criticises Etsuko for not being more “motherly” and sees her as little more than a domestic servant. He has a damaged hand from his wartime service that seems to reflect his wounds, but still rolls in drunk occasionally singing war songs with his inconsiderate friends.

When his father, Ogata (Tomokazu Miura), announces he’s coming to stay with them, Jiro is pleased to see him but rebuffs his request that he talk to an old school friend, Matsuda (Daichi Watanabe), about an article he published claiming that it’s a good thing that teachers like Ogata were let go after the war. Ogata evidently feels hard done by, but it’s also true that the cause of his son’s animosity towards him is that he was a card-carrying militarist who cheered when he left for the front and indoctrinated children with imperialist ideology in his job as a teacher. He is the past Japan must move on from, and a representative of the wartime generation by which the young of today feel betrayed. As Matsuda tells him, it’s a new dawn. Ogata has to change, and so does everyone else including Etsuko who may not be as happy in her marriage as others might assume and may well be seeking other paths towards self-fulfilment rather than allow herself to become another miserable, self-sacrificing housewife.

Even so, the contradictory message seems to be that perhaps you can’t actually move on from this past and Keiko, in particular, may have been changed by her exposure not to the bomb but it’s aftermath, the terrible things she heard and saw amid the wreckage and the stigma she faced afterwards. The artificiality of the Japanese sets might speak to the slipperiness of Etsuko’s memory, as if she were observing a film of herself rather than recalling real events or else reimagining them differently so they play out a little more cinematically, in comparison to the concrete reality of the Sussex bungalow which perfectly captures a lived-in Britishness of the early 1980s. In many ways, Niki might not have clarified very much at all, or perhaps begun to accept the idea that not knowing doesn’t matter in coming to understanding of her relationship with her mother and along with it of herself as she too decides it’s time for change.

A Pale View of Hills screens 16/18th October as part of this year’s BFI London Film Festival.

Trailer (English subtitles)