Sales of Genzaburo Yoshino’s 1937 novel How Do You Live? (君たちはどう生きるか, Kimitachi wa Do Ikiru ka? went through the roof when it was announced that the no longer retired Hayao Miyazaki would be directing a new film with the same title. Predictably, Miyazaki’s film turned out not to be an adaptation at all, or at least not a literal sense, but was intensely interested in the question not so much how do you live but how will you? Will you allow the past to make you bitter and live in a world of pain and resentment, or will you choose to live in a world of peace and beauty free of human malice?

These are of course the questions faced by a post-war generation, the children of Miyazaki’s own era who came of age in a time of fear and suffering. Mahito (Soma Santoki), the hero, loses his mother in the firebombing of Tokyo. He runs through a world of shadows to save her from the flames but of course, he cannot. A year later everything has changed. His father has remarried, taking his mother’s younger sister Natsuko (Yoshino Kimura) as his new wife. Natsuko is now pregnant which suggests the relationship began some time ago though Mahito knew nothing of it and had no recollection of ever having met Natsuko before being sent to live in her giant mansion in the country more or less untouched by the war.

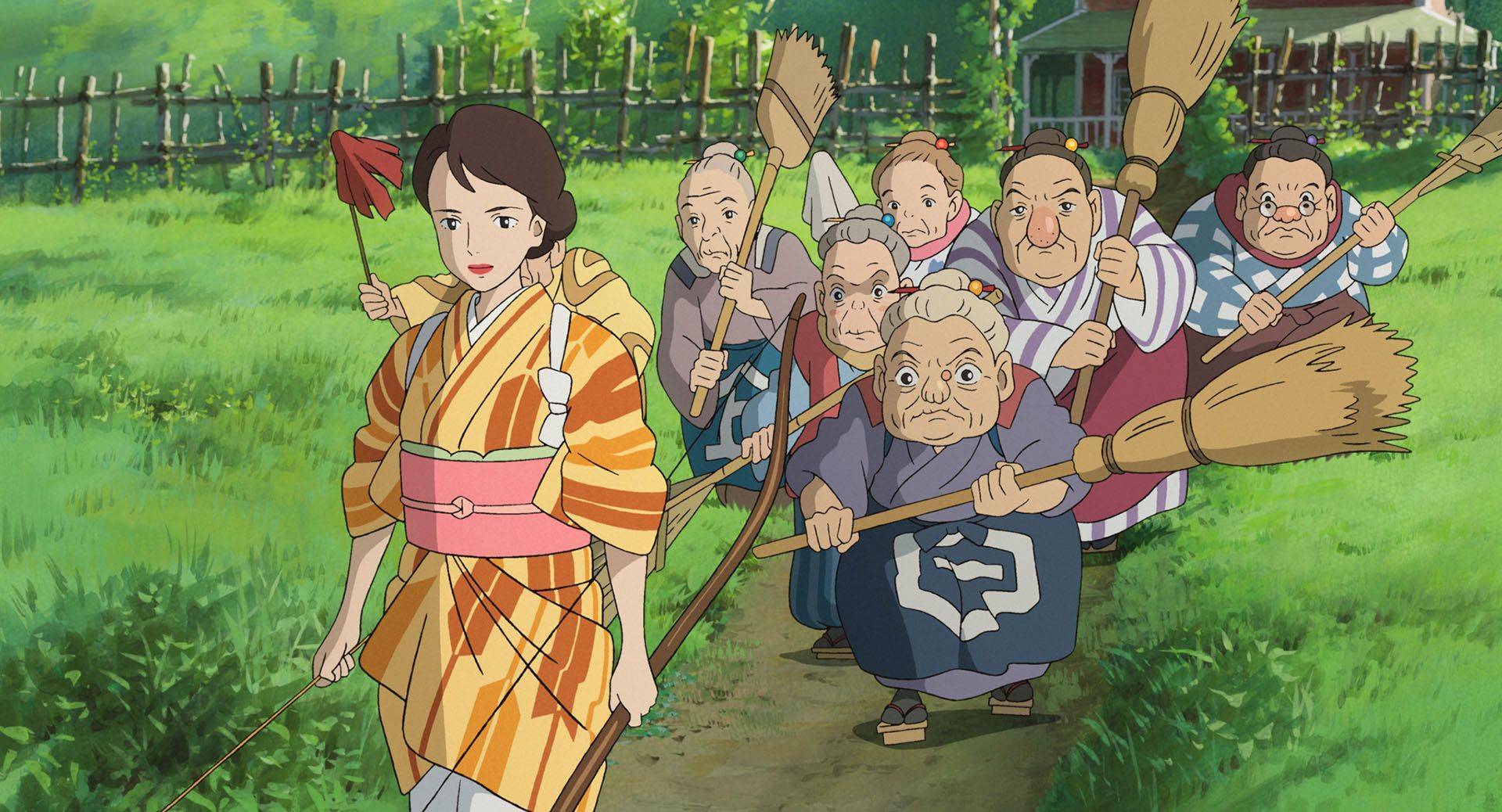

It’s here that Mahito’s own malice rises. He is polite, if sullen, but cannot warm to his new stepmother and resents his father’s relationship with her. Perpetually bothered by a grey heron (Masaki Suda) his first thought is to kill it, crafting a bow and arrow from bamboo and one of the heron’s own feathers. Shunned as the new boy at school he hits himself on the head with a rock while his father, Shoichi (Takuya Kimura), comically vows revenge and lets him stay home. As he points out, there’s not much “education” going on anyway with most of the students pulled away from their studies for “voluntary” labour in service of the war effort in this case agricultural.

Shoichi has moved to the country to open a factory which it seems produces canopies for fighter planes which is all to say that he is profiting from the business of war, though transgressively referencing the failure in Saipan over breakfast with the mild implication that it might work out alright for him. There is after all a grim reason they’ll be in need of large numbers of aircraft parts in the near future. Mahito’s dark impulses are directly linked to those of militarism and the folly of war. When he finally enters the tower of madness apparently constructed by a great-uncle who went insane through reading too many books, he discovers that his enemies are an ever expanding clan of fascistic, man-eating parakeets led by a Mussolini-like despotic leader attempting to manipulate the Master of the tower.

Inside the tower is a land out of time, a place for those already dead or in essence an eternal past. It’s here that Mahito is presented with a choice, how will he live? Will he choose malice and destruction, or will he choose to leave and build a new world of beauty and peace above? In many ways, the important point is that the choice is his as it is ours, that we are free to decide and that our choices create the world in which we live. Through his adventures in the tower, Mahito begins to come to terms with his situation and resolves to accept Natsuko as a mother and make friends of those he once considered enemies. When the tower itself crumbles, it takes with it the last vestiges of authoritarianism and tyranny.

Prompting his epiphany, Mahito discovers a copy of How Do You Live? in his room, a present from his late mother inscribed to the grown-up Mahito. He is surrounded by the world’s ugliness, forced into a surprisingly graphic fish gutting session that leaves him wiping away blood, recalling his profusely bleeding head injury and the scar it will forever mark him with. Pelicans imprisoned in the other world meanwhile tell him that they have no choice but to behave as they do for the Master of the Tower neglected to put enough fish in the rivers intending them to destroy rather nurture new life while their young too learn all the wrong lessons. Yet there is beauty and strangeness here too, along with kindness and humanity. Boundlessly inventive, Miyazaki couples surrealist visions of murderous birds and the hellish scenes of a city on fire with Mahito the only figure visible in his pale blue school uniform darting through the soot and the shadows. A vivid symphony of life, the film may in its way be about grief and the pain of moving on but finally discovers a kind of serenity in an accommodation with the present and the eternally unfinished question of how you yourself will live.

The Boy and the Heron screened as part of this year’s BFI London Film Festival.