After the initial trilogy, the Shinobi no Mono series has changed direction following instead another ronin, Saizo, opposed to the Tokugawa because the promised world of peace had no room for ninja. Nevertheless, as time moved on, the sixth instalment shifted again to follow Saizo’s son, Saisuke, who continued his father’s vendetta against the Tokugawa but largely found himself frustrated by the times in which he lived. Nevertheless, film seven picks back up with Saizo and takes place in 1616 shortly after the siege of Osaka.

Having joined up with a band of other displaced ninja, it seems that Saizo (Raizo Ichikawa) has had the rather unusual charge of heart in that his experiences with Yukimura have apparently convinced him to devote himself to serving a lord rather than living wild and free as a ninja while he still has a burning desire to kill Ieyasu but mainly for personal revenge. This is partly in recognition that he’s realised the Tokugawa are here to stay and politically it won’t make any difference killing Ieyasu as one of his underlings will simply move up to take his place.

The other problem that he has is that there seems to be a mole and the other ninja have all settled on Akane (Shiho Fujimura) as the likely source of the treachery seeing as she is a “kunoichi” and therefore not a real ninja. Akane of course rejects this, but has also fallen in love with Saizo, which is of course against the ninja code. Saizo somewhat reinforces the sexist message by telling her to think of her pride and happiness as a woman, both things that a female ninja is expected to reject. Even so, he does not agree with his fellow ninja that she is the traitor and does not reject her affections in quite the way he usually does. Meanwhile, the gang is also in touch with another woman, Yayoi (Yuko Kusunoki), a maid to Lady Sen who also claims to be looking for revenge against the Tokugawa as her father was killed at Osaka Castle while her clan is also opposed to Ieyasu.

Ever duplicitous, Ieyasu sends his own ninja against them. Led by Fuma Daijuro (Takahiro Tamura), the clan is apparently an ancient enemy of the Iga with whom they’ve long been waiting for a showdown only they don’t usually leave their home promise. The vendetta pushes the film back into regular jidaigeki tragedy, if one with a spy element as Saizo and the others try to figure out the identity of the mole while plotting to kill Ieyasu. The other ninja are somewhat blinded by their own preferences despite the prohibitions against human feeling though they do eventually admit their mistakes and apologise.

This one is perhaps a little nastier with the rival gang calling Akane a whore and threatening to rape her while the Tokugawa also admit they plan to tie up loose ends by knocking off the mole when they’re no one longer useful. Returning to the director’s chair, Kazuo Mori leans more towards a classic samurai aesthetic, but nevertheless stays close to the series’ nihilistic atmosphere which is perhaps deepened by the solidifying of the Tokugawa regime which makes the ninja’s existence more or less redundant. In a slightly meta motif, this film overlaps with the last of the original trilogy in which Goemon does in fact bring about Ieyasu’s death even if, as Ieyasu says, he was old and would have died soon anyway though now he now goes out at the top of his game having achieved all of his major life goals.

It does however adopt the slightly more fantastical trappings of the later films in its flaming shrunken and whirring fire whips not to mention the spear action from Fuma’s gang. The final showdown takes place amid copious snow echoing the coldness of the ninja lifestyle in which human emotions are largely forbidden while not even fellow ninja can really be trusted. Trusting only his mission, Saizo cuts a lonely figure and cannot seem to separate himself from it, running fast towards Edo and a confrontation with politics hoping to start a domino effect, resulting in the decline of the Tokugawa through a simple process of elimination.

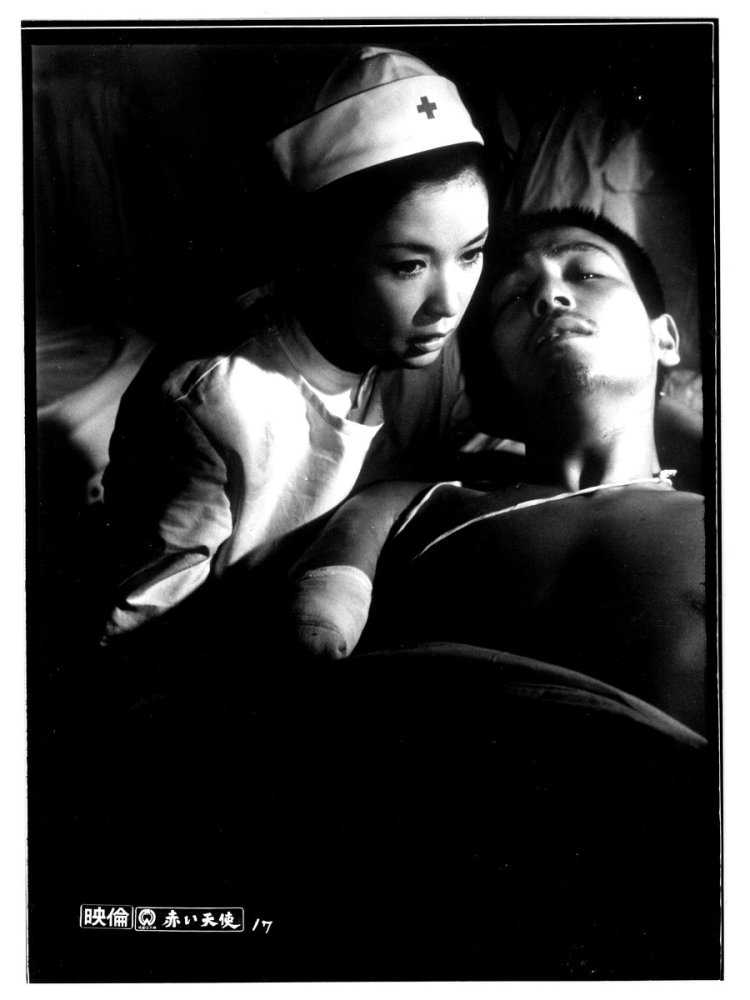

Red Angel (赤い天使, Akai Tenshi) sees Masumura returning directly to the theme of the war, and particularly to the early days of the Manchurian campaign. Himself a war veteran (though of a slightly later period), Masumura knew first hand the sheer horror of warfare and with this particular film wanted to convey not just the mangled bodies, blood and destruction that warfare brings about but the secondary effects it has on the psyche of all those connected with it.

Red Angel (赤い天使, Akai Tenshi) sees Masumura returning directly to the theme of the war, and particularly to the early days of the Manchurian campaign. Himself a war veteran (though of a slightly later period), Masumura knew first hand the sheer horror of warfare and with this particular film wanted to convey not just the mangled bodies, blood and destruction that warfare brings about but the secondary effects it has on the psyche of all those connected with it.