Everything is facade in Yasuzo Masumura’s ironic exploration of the corruptions of the post-war society, Two Wives (妻二人, Tsuma Futari). Based on the novel by Patrick Quentin and scripted by Kaneto Shindo, Masumura’s dark mystery drama is a characteristically circular affair revolving around the hero’s moral confusion but positioning its two women as mirrors of each other, one a conservative upperclass daughter of a magazine editor whose intense properness has alienated all around her, and the other a perpetual mistress hung up on no-good starving artists.

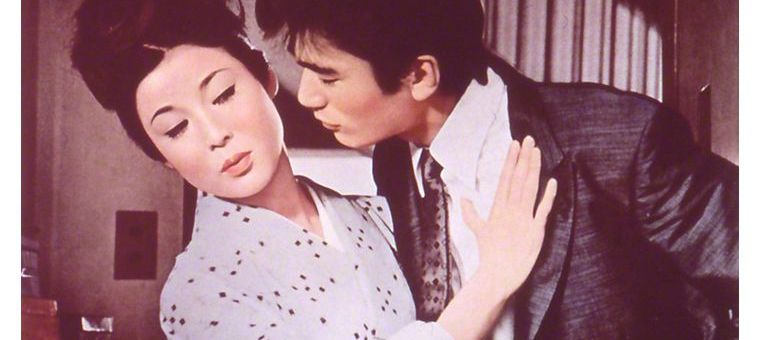

Kenzo (Koji Takahashi), the hero, is married to the upperclass Michiko (Ayako Wakao) but is accidentally reunited with former uni girlfriend Junko (Mariko Okada) through an act of extreme coincidence. Junko is sporting a bandage around her neck to hide bruises caused by her violent drunk of a boyfriend Kobayashi (Takao Ito), a failed writer. This is in a sense ironic, as Kenzo had himself been an aspiring author during their uni days and it was Junko’s introduction to an old family friend, Nagai (Masao Mishima), which resulted in him getting a regular salaryman job before dumping her to marry the boss’ daughter. Despite himself, Kenzo ends up doing the same thing for Kobayashi but the young man’s motives are less than pure and he’s not so much tempted by consumerist comforts as coldly avaricious quickly setting his sights on Michiko’s wayward younger sister Rie (Kyoko Enami) who is just young and reckless enough to rebel against her sister’s puritanism through an affair with an unsuitable man.

The magazine, Housewife’s World, seems to have been Michiko’s brainchild and runs under the slogan “clean, bright, beautiful”. Its target demographic is conservative wives and mothers with a particular interest in wholesome family values. These are all things Michiko practices in her personal life though as it becomes clear her excessive properness often annoys those around her who claim her moral authoritarianism pushes them towards transgressive rebellion. As the film opens, Nagai holds a meeting in which he announces that he’s fired two employees for being cautioned by the police when caught in an after-hours nightclub fearing that if such an event were to make to the papers it would tarnish their brand. However, pretty much no one other than Michiko is very dedicated to wholesomeness, her father having married off his mistress to a penniless aristocrat for the prestige of his name while employing the couple to manage a fund Michiko had set up for disabled children only for them to siphon all the money off for themselves.

Having chosen consumerist fulfilment over the romantic, Kenzo has dedicated himself to his new role but is perhaps still conflicted in his decision especially after reuniting with Junko. His mirror Kobayashi, however, has no conflict at all and is willing to do anything and everything to achieve consumerist success. “You’ve no idea what a man without standing or money will do” he snarls, laying bare the effects of post-war inequality, pledging to use the Nagais like a springboard to jump as high as he can while threatening blackmail over having discovered all the sordid goings on at Housewife’s World.

The soul of properness, Michiko is presented as the ultimate image of respectability while Junko is perceived as its inverse, a sexually active unmarried woman living in squalid backrooms and hanging out in bars. Yet Michiko’s austere exterior hides an inner ruthlessness in addition to an internal conflict over her own role in society. She publishes a magazine aimed at housewives though she is not a housewife herself but technically her husband’s boss. Eventually Nagai attempts to promote Kenzo above his wife claiming that the present situation does not fit with the traditional patriarchal outlook of magazine but he refuses, uncomfortable with this little piece of political manoeuvring in thinking that Michiko is better suited to the job and mildly insulted by the attempt at manipulation knowing that the reason for his promotion has nothing to do with his own ability. “I’m not interested in being a dog” he eventually barks back having come to the conclusion that this life of consumerist comfort is not worth the sacrifice of his autonomy or dignity.

As for Junko, her love is indeed selfless continuing to support each of her starving artists even after they abandon her in favour of conventional success. Faced with Kobayashi’s rage, she cannot fire he effortlessly taking the gun from her which will eventually be retrieved by Michiko who does indeed use it to defend herself after Kobayashi attempts to rape her. “I want to be a woman who is loved like you” she exclaims on meeting Junko who has been accused of the murder she herself committed, jealous of her warmth and openness while Junko envies her for her refinement. Michiko claims that she hates lies, but discovers that everyone in her life has been lying to her while eventually forced to lie herself in covering up her crime. Yet it’s the weight of all the lies which eventually jolts Kenzo out of his complicity, resenting being made to lie to the police to cover up Rie’s potentially scandalous behaviour while unwilling to allow Junko to be convicted of a crime she did not commit. Nagai even convinces the family maid to lie for them in order to guarantee medical treatment for her sickly daughter.

At his cruelest moment, Nagai goes so far as to undercut Michiko’s conflicted sense of self in telling her coldly that he only considered her a “token figure” he used for business who should have known her place and sat quietly in a corner ironically relegating her to the patriarchal space to which she on some level feels she ought to have confined herself while simultaneously wanting to take control as she had when she informed her father she would be marrying Kenzo rather than allowing him to find her a match. She too had worried about the direction of the current society and their magazine, wanting to move away from pure consumerism towards socially conscious content while her father clearly just wanted to make as much money as possible with no particular concern for morality only for optics. When she asks Kenzo if he loves her, he does not lie but replies only that he respects her which might in a way be an expression of love, later claiming that the properness which has alienated everyone else has in fact made him a better person who is determined to stand by her after she eventually commits to doing the right thing.

In a final touch of irony, we see the “clean, bright” slogan echoed on a billboard outside the police station which is probably not an entirely transparent agency either though it appears as if in this case justice legal, moral, and emotional will be served striking back against amoral post-war consumerism and societal hypocrisy as the circle is brought to a close, both women landing on an equal footing and making their respective choices while Kenzo recommits himself to decency by pledging to start over together with Michiko. All in all, a more optimistic ending that might be assumed in a Masumura picture but then again no one can ever really escape the insidious hypocrisies of the contemporary society.

Original trailer (no subtitles)

By 1962 the Japanese economy had begun to improve and with the Olympics on the horizon the nation was beginning to look forward towards hoped for prosperity rather than back towards the intense suffering that had defined the post-war era. There would be, however, a kind of reckoning to be had if not quite yet. Yuzo Kawashima’s Elegant Beast (しとやかな獣, Shitoyakana Kemono) is perhaps among the first to start asking questions about what the legacy of the immediate aftermath of the war might be. It may have been impossible to survive with one’s integrity entirely intact, but how should one proceed now that there is less need to be so self serving, calculating, and cruel when there is more food on the table?

By 1962 the Japanese economy had begun to improve and with the Olympics on the horizon the nation was beginning to look forward towards hoped for prosperity rather than back towards the intense suffering that had defined the post-war era. There would be, however, a kind of reckoning to be had if not quite yet. Yuzo Kawashima’s Elegant Beast (しとやかな獣, Shitoyakana Kemono) is perhaps among the first to start asking questions about what the legacy of the immediate aftermath of the war might be. It may have been impossible to survive with one’s integrity entirely intact, but how should one proceed now that there is less need to be so self serving, calculating, and cruel when there is more food on the table?