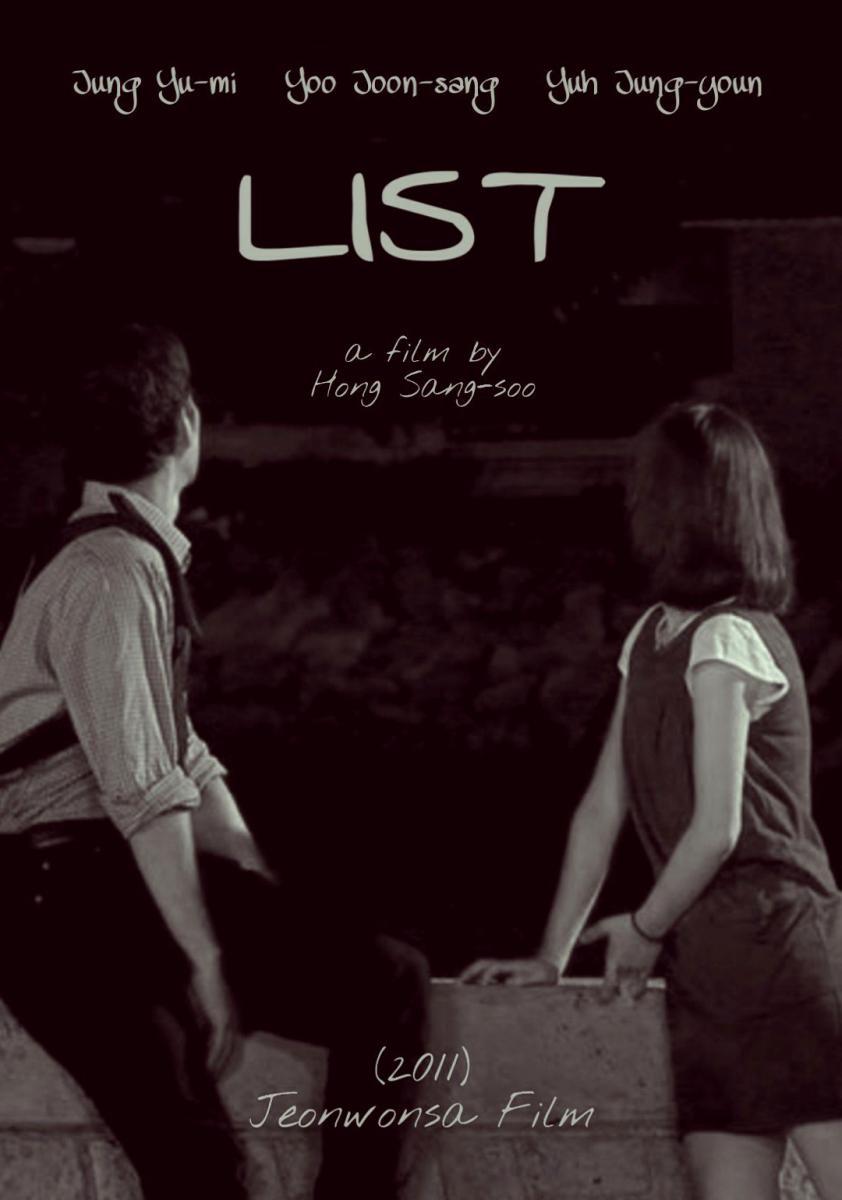

Hong Sang-soo finds himself in a positive, if characteristically melancholy, mood for his hard to see 2011 short, List (리스트). Short as a companion piece to In Another Country, the film opens with the exact same scene as a mother and daughter bicker about the sorry circumstances which have forced them to retreat to the seaside where they’ll be living in peaceful seclusion. This time however, young(ish) Mihye (Jung Yu-mi) sits down to write not a screenplay but a list, a kind of itinerary in order to make the most of this deliberately boring “vacation” taken all alone with her nice but “concerned” mother (Youn Yuh-jung).

Mihye’s List runs right through the day and includes normal holiday activities like having a meal in a famous restaurant, checking out the mudflats, and buying souvenirs, as well as reminders to giver her mum a massage and let her know she’s loved, and a few idiosyncratic suggestions too. Perhaps what she’s really the most excited about is trying out her new tooth brushing technique! At night she plans to dream of “prince charming” which is also something her mother later brings up in pushing a little on why the near 30-year-old Mihye has no boyfriend and is not yet married. Mihye’s mother worries that she has no desires before dialling back and suggesting that Mihye has desires but not the courage to act on them.

This will, perhaps, prove to be true when Mihye and her mother meet a nice man just sitting on the beach as if waiting for them. Unsurprisingly, the man turns out to be a film director but he’s a far cry from Hong’s general leads. Sanjun (Yu Jun-sang) is a nice, wounded young man who might be slightly awkward but in an affable way. Though Mihye’s mother is taken with him, Mihye isn’t so sure. He seems kind of like a prince charming, but then again he’s just a random man they met on a beach who turns out to be famous and successful. Claiming that her daughter is “shy”, Mihye’s mother agrees to Sanjun’s invitation to a date on Mihye’s behalf (which was bizarrely directed to her anyway) and then offers to come along despite Mihye’s double protests.

Tellingly, Hong departs from his usual aesthetic with key scenes shot on obvious sets and a strange absence of energy even in those taking place on location. Mihye muses and her fantasies appear to come to life. She completes her list for the day almost by accident while in the company of the prince charming she requested. Still, she isn’t sure. She asks him why he likes her but his answers are vague and perhaps worrying. He likes her “purity” and thinks she’s cute. She’s “special” in a way no one can see. All things Mihye’s wants to hear but doesn’t quite believe. Later she tells Sanjun she’s frightened of what her life will become, that she’s trapped by her mother and feels, in some way, damaged by her though she fails to elaborate further. In true fairytale style the romance escalates improbably, culminating in lifelong declarations of love and a promise of mutual salvation.

Mihye wonders why people can’t see the good right in front of them. Sanjun replies it’s because they’re too focused on indulging themselves in the now. Yet what Mihye learns is perhaps that occasional fantasies are OK, that vague lists are useful because they leave you open to possibilities while lessening the fear of disappointment, and that even if your mother thinks your plans are “too ambitious”, it doesn’t really matter, you can just see where they go. Mihye might not have cured any of those anxieties. Perhaps she still feels trapped, resentful, even hopeless, but the sun rises anew and there’s another day to explore. It’s as cheerful an ending as Hong can muster, hope mixed with melancholy resignation and a stoic determination to put a brave face on existential despair.

Finding the sinister in the commonplace is the key to creating a chilling horror experience, but “finding” it is the key. Attempting to graft something untoward onto a place it can’t take hold is more likely to raise eyebrows than hair or goosebumps. The creators of Korean horror exercise Manhole (맨홀) have decided to make those ubiquitous round discs the subject of their enquiries. They are kind of worrying really aren’t they? Where do they go, what are they for? Only the municipal authorities really know. In this case they go to the lair of a weird serial killer who lives in the shadows and occasionally pulls in pretty girls from above like one of those itazura bank cats after your loose change.

Finding the sinister in the commonplace is the key to creating a chilling horror experience, but “finding” it is the key. Attempting to graft something untoward onto a place it can’t take hold is more likely to raise eyebrows than hair or goosebumps. The creators of Korean horror exercise Manhole (맨홀) have decided to make those ubiquitous round discs the subject of their enquiries. They are kind of worrying really aren’t they? Where do they go, what are they for? Only the municipal authorities really know. In this case they go to the lair of a weird serial killer who lives in the shadows and occasionally pulls in pretty girls from above like one of those itazura bank cats after your loose change.

Many people all over the world find themselves on the zombie express each day, ready for arrival at drone central, but at least their fellow passengers are of the slack jawed and sleep deprived kind, soon be revived at their chosen destination with the magic elixir known as coffee. The unfortunate passengers on an early morning train to Busan have something much more serious to deal with. The live action debut from one of the leading lights of Korean animation Yeon Sang-ho, Train to Busan (부산행, Busanhaeng) pays homage to the best of the zombie genre providing both high octane action from its fast zombie monsters and subtle political commentary as a humanity’s best and worst qualities battle it out for survival in the most extreme of situations.

Many people all over the world find themselves on the zombie express each day, ready for arrival at drone central, but at least their fellow passengers are of the slack jawed and sleep deprived kind, soon be revived at their chosen destination with the magic elixir known as coffee. The unfortunate passengers on an early morning train to Busan have something much more serious to deal with. The live action debut from one of the leading lights of Korean animation Yeon Sang-ho, Train to Busan (부산행, Busanhaeng) pays homage to the best of the zombie genre providing both high octane action from its fast zombie monsters and subtle political commentary as a humanity’s best and worst qualities battle it out for survival in the most extreme of situations. Because it’s there. As good a reason as any for doing anything but these were the only three words of explanation offered by George Mallory in answer to the question “Why climb Everest?”. In Powell & Pressburger’s The Red Shoes, the heroine reacts in a similarly philosophical fashion when asked “Why do you want to dance?” replying with the question “Why do you want to live?”. What makes some people prepared to dance until their feet bleed and their toes break, and sends others to the peaks of snowcapped mountains staring death in the face as they go, is something which cannot be fully explained in words but cannot be denied by those who hear its calling.

Because it’s there. As good a reason as any for doing anything but these were the only three words of explanation offered by George Mallory in answer to the question “Why climb Everest?”. In Powell & Pressburger’s The Red Shoes, the heroine reacts in a similarly philosophical fashion when asked “Why do you want to dance?” replying with the question “Why do you want to live?”. What makes some people prepared to dance until their feet bleed and their toes break, and sends others to the peaks of snowcapped mountains staring death in the face as they go, is something which cannot be fully explained in words but cannot be denied by those who hear its calling.