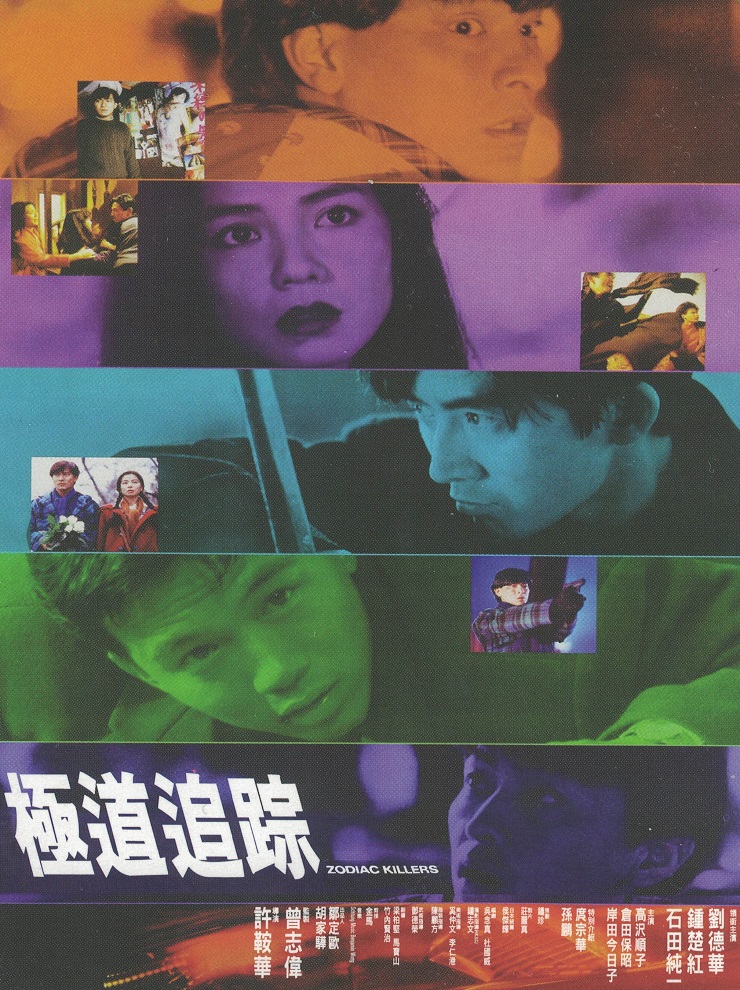

Melancholy exiles seeking a better future find only futility in the dying days of the bubble economy in Ann Hui’s 1991 gangster drama, Zodiac Killers (極道追踪). The English title is admittedly misleading, there’s seemingly no connection to any kind of “zodiac” and no hint of conspiracy murder except those forced by the world’s enduring cruelty, though the Chinese is perhaps equally so meaning something like “yakuza pursuit” which is accurate but only to a point.

The hero, Ben (Andy Lau Tak-wah), has come to Tokyo from Hong Kong to study film but rarely goes to classes, preferring to learn how to make money instead. Making the most of the then affluent city, he works as a tour guide for Chinese tourists, dutifully delivering the men to the strip clubs of Shinjuku in the evenings for kickbacks and giving his boss a kicking when he tries to stiff him out of the agreed amount, heading to his second job in a kitchen immediately afterwards. “Man does not live to make money only, you must learn to spend it too”, he explains to his friend, Chang (Tou Chung-hua), persuading him to come hang out in a swanky bar they’ve been invited to by Ben’s shady relative Ming (Suen Pang) who is currently trying to make it as a yakuza by marrying the boss’ mama-san sister Yuriko (Junko Takazawa). It’s at the bar that Ben first sets eyes on Tieh-lan (Cherie Chung Chor-hung), a young woman from the Mainland in Tokyo studying at a Japanese language school and working as a hostess to make ends meet though as she points out “not every Chinese girl likes to work here”, instantly offending Ming but interestingly not Yuriko who seems sympathetic if embarrassed.

All of them are in Tokyo because at that moment in time Japan looked like the future, though the window was rapidly closing. Tieh-lan is beginning to wonder why she came. Her friend Mei-mei (Tsang Wai-fai) has ended up in an unwanted sexual relationship with the man who sponsored their visas, Harada (Law Fei-yu), who nevertheless continually sexually harasses Tieh-lan. “Why did we come here?”, Tieh-lan asks Mei-mei, “for our future or for men? You can debase yourself at home, why have you come to Japan to do it?”. Ben later asks something similar of Ming who freely admits that he is prepared to sell his body for influence, “satisfying” Yuriko in order to buy influence with her brother and be admitted into his yakuza clan. The Tokyo they inhabit is one steeped in exile. They surround themselves with other Chinese migrants, be they from the Mainland, Hong Kong, or Taiwan, and congregate in the seedier parts of Shinjuku living on the fringes of society, working as bar hostesses, or gangsters, or in kitchens. For Ben whose bachelor pad student dorm is adorned with posters of Bruce Lee and Rocky, his purpose is more adventure and youthful longing for freedom than escape which is why he makes a point of ignoring his loving mother’s phone calls, but even he struggles to find what he needs on the unforgiving streets of a hostile city.

That hostility is first brought home to him by a gang of ultranationalist bikers flying the imperial flag one of whom threatens him with a samurai sword (a moment which is tragically echoed in the film’s nihilistic conclusion). They are not, however, the only ones feeling displaced, as a heartbreaking cameo from golden age star Kyoko Kishida as an ageing geisha makes plain. Asano (Junichi Ishida), the melancholy yakuza with whom Tieh-lan has fallen in love much to Ben’s disappointment, declares himself “always a loner”, returning to Tokyo after years of exile in South America. An orphan, Asano laments that the beach he visited as child no longer exists and the city he’s come home to is changed beyond all recognition. Perhaps for that reason he falls for melancholy exile Tieh-lan as they bond in a shared sense of hopeless rootlessness.

With the surprise introduction of Asano, Hui transitions into the moody noir with which the film opened, shots of Andy Lau plaintively looking back at the shore from a boat on the open sea intercut with Cherie Chung walking sadly through an empty, neon-lit city. Asano hoped for reconciliation but found only betrayal, there can be no home for exiles even if they return. The trio’s broken dreams find their final expression in the nihilistic violence of a non-existent yakuza war. Asano’s final gesture was one only of futility, no one wants to hear his inconvenient truth because the clans in question have already made “peace” and are intent on working together for future prosperity. “Your heart is too soft for this wicked world” Ming says of Ben but it’s a statement that rings true for them all, living life by movie logic in which good will eventually triumph. Ming sees no point in returning to Hong Kong because he’d be a nobody, tragically believing that being a gang boss’ brother-in-law is close enough to somebody in Shinjuku. Only Chang, who came to Japan to look for his missing sweetheart, manages to keep himself safe but largely, as we later find out during a rather bizarre sequence featuring a surprise outdoor porno shoot, because he does not yet know that his dream is futile too. A chronicle of a world in collapse, Zodiac Killers leaves its marginalised heroes with no place left to run, permanent exiles denied safe harbour sailing towards a promised horizon with no land in sight.

Original trailer (no subtitles)

Yoshimitsu Morita is an enigma. While directing some of the most acclaimed Japanese films of the 80s including

Yoshimitsu Morita is an enigma. While directing some of the most acclaimed Japanese films of the 80s including