Still most closely associated with his debut feature Hausu – a psychedelic haunted house musical, Nobuhiko Obayashi’s affinity for youthful subjects made him a great fit for the burgeoning Kadokawa idol phenomenon. Maintaining his idiosyncratic style, Obayashi worked extensively in the idol arena eventually producing such well known films as The Little Girl Who Conquered Time (starring Kadokawa idol Tomoyo Harada) and the comparatively less well known Miss Lonely and His Motorbike Her Island (starring a very young and extremely skinny Riki Takeuchi). 1981’s School in the Crosshairs (ねらわれた学園, Nerawareta Gakuen) marks his first foray into into the world of idol cinema but it also stars one of Kadokawa’s most prominent idols in Hiroko Yakushimaru appearing just a few months before her star making role in Shinji Somai’s Sailor Suit and Machine Gun.

Still most closely associated with his debut feature Hausu – a psychedelic haunted house musical, Nobuhiko Obayashi’s affinity for youthful subjects made him a great fit for the burgeoning Kadokawa idol phenomenon. Maintaining his idiosyncratic style, Obayashi worked extensively in the idol arena eventually producing such well known films as The Little Girl Who Conquered Time (starring Kadokawa idol Tomoyo Harada) and the comparatively less well known Miss Lonely and His Motorbike Her Island (starring a very young and extremely skinny Riki Takeuchi). 1981’s School in the Crosshairs (ねらわれた学園, Nerawareta Gakuen) marks his first foray into into the world of idol cinema but it also stars one of Kadokawa’s most prominent idols in Hiroko Yakushimaru appearing just a few months before her star making role in Shinji Somai’s Sailor Suit and Machine Gun.

Set once again in a high school, School in the Crosshairs is the ultimate teen movie for any student who’s ever suspected their place of education has been infiltrated by fascists but no one else has noticed. Top student Yuka (Hiroko Yakushimaru) is the archetypal Obayashi/idol movie heroine in that she’s not only bright and plucky but essentially good hearted and keen to help out both her friends and anyone else in trouble. Her life changes when walking home from school one day with her kendo obsessed friend Koji (Ryoichi Takayanagi) as the pair notice a little kid about to ride his tricycle into the path of a great big truck. Yuka, horrified but not quite knowing what to do, shouts for the little boy to go back only it’s time itself which rewinds and moves the boy out of harm’s way. Very confused and thinking she’s had some kind of episode, Yuka tests her new psychic powers out by using them to help Koji finally win a kendo match but when a strange looking man who claims to be “a friend” (Toru Minegishi) arrives along with icy transfer student Takamizawa (Masami Hasegawa), Yuka finds herself at the centre of an intergalactic invasion plot.

Many things have changed since 1981, sadly “examination hell” is not one of them. Yuka and Koji still have a few years of high school left meaning that it’s not all that serious just yet but still, their parents and teachers have their eyes firmly on the final grades. Yuka is the top student in her class, much to the chagrin of her rival, Arikawa (Macoto Tezuka), who surpasses her in maths and English but has lost the top spot thanks to his lack of sporting ability. Koji is among the mass of students in the middle with poor academic grades but showing athletic promise even if his kendo career is not going as well as hoped.

Given everyone’s obsession with academic success, the aliens have hit on a sure thing by infiltrating a chain of cram schools promising impressive results. Grades aside, parents are largely laissez-faire or absent, content to let their kids do as they please as long as their academic life proceeds along the desired route. Koji’s parents eventually hire Yuka as a private teacher to help him improve only for her to help him skip out to kendo practice. Her parents, by contrast, are proud of their daughter and attentive enough to notice something’s not right but attribute her recent preoccupation to a very ordinary adolescent problem – they think she’s fallen in love and they should probably leave her alone to figure things out her own way. A strange present of an empty picture frame may suggest they intend to give her “blank canvas” and allow her to decide the course of her own life, but she has, in a sense, earned this privilege through proving her responsible nature and excelling in the all important academic arena.

School is a battlefield in more ways than one. Intent on brainwashing the teenagers of Japan, “mysterious transfer student” Takamizawa has her sights firmly set on taking over the student council only she needs to get past Yuka to do it. Takamizawa has her own set of abilities including an icy stare which seems to make it impossible to refuse her orders and so she’s quickly instigated a kind of “morality” patrol for the campus to enforce all those hated school rules like skirt lengths, smoking, and running in the halls. Before long her mini militia has its own uniforms and creepy face paint but her bid for world domination hits a serious snag when Yuka refuses to cross over to the dark side and join the coming revolution. Asking god to grant her strength Yuka stands up to the aliens all on her own, avowing that she likes the world as it and is willing to sacrifice her own life for that of her friends. Accused of “wasting” her powers, Yuka asks how saving people could ever be “wasteful” and berates the invaders for their lack of human feeling. Faced with the cold atmosphere of exam stress and about to be railroaded into adulthood, Yuka dreams of a better, kinder world founded on friendship and basic human goodness.

Beginning with a lengthy psychedelic sequence giving way to a classic science fiction on screen text introduction Obayashi signals his free floating intentions with Yuka’s desaturated bedroom floating over the snowcapped mountains. Pushing his distinctive analogue effects to the limit, Obayashi creates a world which is at once real and surreal as Yuka finds herself at a very ordinary crossroads whilst faced with extraordinary events. Courted by the universe, Yuka is unmoved. Unlike many a teenage heroine, she realises that she’s pretty happy with the way things are. She likes her life (exam stress and all), she loves her friends, she’ll be OK. Standing up for the rights of the individual, but also for collective responsibility, Yuka claims her right to self determination but is determined not to leave any of her friends behind.

Original trailer (no subtitles)

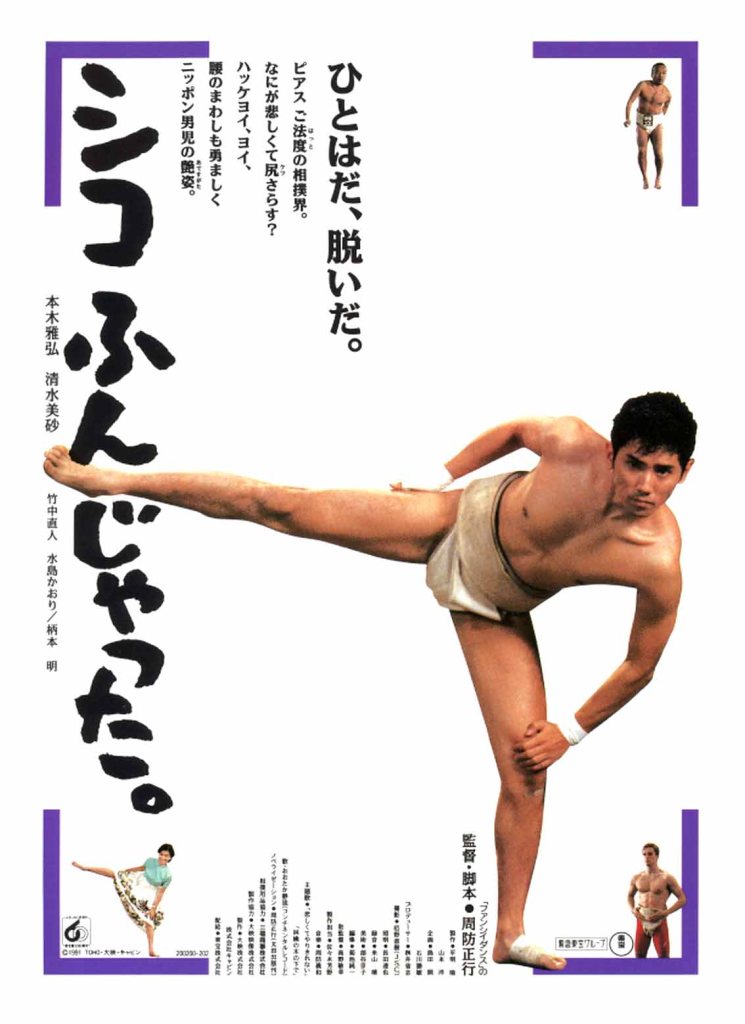

Considering how well known sumo wrestling is around the world, it’s surprising that it doesn’t make its way onto cinema screens more often. That said, Masayuki Suo’s Sumo Do, Sumo Don’t (シコふんじゃった, Shiko Funjatta) displays an ambivalent attitude to this ancient sport in that it’s definitely uncool, ridiculous, and prone to the obsessive fan effect, yet it’s also noble – not only a game of size and brute force but of strategy and comradeship. Not unlike Suo’s later film for which he remains most well known, Shall We Dance, Sumo Do, Sumo Don’t uses the presumed unpopularity of its central activity as a magnet which draws in and then binds together a disparate, originally reluctant collection of central characters.

Considering how well known sumo wrestling is around the world, it’s surprising that it doesn’t make its way onto cinema screens more often. That said, Masayuki Suo’s Sumo Do, Sumo Don’t (シコふんじゃった, Shiko Funjatta) displays an ambivalent attitude to this ancient sport in that it’s definitely uncool, ridiculous, and prone to the obsessive fan effect, yet it’s also noble – not only a game of size and brute force but of strategy and comradeship. Not unlike Suo’s later film for which he remains most well known, Shall We Dance, Sumo Do, Sumo Don’t uses the presumed unpopularity of its central activity as a magnet which draws in and then binds together a disparate, originally reluctant collection of central characters.