Why is it that we rush to judgement rather than empathy? When a little girl disappears during a short walk from a local park to her home, less than helpful members of the public are quick to turn on the parents while news media, eager for ratings and clicks, is only too happy to give the people what they want casting aside ethical concerns in their exploitation of the parents’ pain all while the little girl remains missing.

In this society, it’s quite normal culturally for children of Miu’s age, six, to walk short distances alone and be left unsupervised at home at for short periods of time. Nevertheless, the public is quick to blame the mother, Saori (Satomi Ishihara), because she had gone to a concert that night and didn’t notice frantic calls from her husband worried because Miu was not at home when he got back from work at 7pm. Soari too blames herself, as is perhaps natural, but it’s unreasonable to expect anyone to never go out for an evening again after having children. Her husband comes in for less scrutiny, which might be surprising, though her brother, Keigo (Yusaku Mori), soon finds himself the prime suspect having been the last to see Miu and allowed her to walk home alone though he would previously have walked her back.

The family find themselves under scrutiny with their every move judged by an unforgiving society. When they dare to buy fancy pastries, online trolls suggest they can’t be all that bothered about Miu after all and are living the high life with the extra money they no longer need to spend on her. Given all that, it might be surprising that they turn to the media for help but in their desperation to find Miu they will leave no stone unturned. Idealistic reporter Sunada (Tomoya Nakamura) seems to want to help them, but is constantly undermined by his bosses who pressure him to take the story into more sensational territory. Though he wanted to write a human interest piece supporting the parents and raising awareness about Miu’s disappearance, he ends up placing them in the firing line for even more trolling and particularly of Saori’s brother Keigo who is an introverted, awkward man not suited to appearing on television.

Sunada says he wants to help, but it’s undeniable that the media is exploiting the parents’ desperation raising serious ethical concerns as to how they safeguard sources and subjects while shaping the narrative around sensitive issues. Sunada takes a producer to task for placing images of a cement mixer and the sea into the ident for the piece as if it were hinting at what might have happened to Miu but really what the station is most interested in is digging up dirt on the family rather than drawing out new information on the case. A fellow journalist is having great success with a salacious story about the mayor’s son committing fraud, but his piece is less crusading investigative journalism than gossip inviting judgement. Disliking his flippant attitude, Sunada reminds him their job’s not to make people laugh, but his colleague gets a fancy promotion to head office while Sunada is stuck doing random feel good stories about seals.

Their treatment at the hands of the media also exposes a divide within the couple with Saori often frustrated by her husband’s attitude, feeling as if he isn’t invested enough. Yutaka (Munetaka Aoki) suggests simply not reading the online comments and ignoring the trolls while Saori feels compelled to defend herself. He is also warier of pranks and scammers, unwilling to simply jump on every lead out of desperation when so many people seem intent on causing them further pain. Perhaps it makes people feel more in control of their lives to blame the parents, as if something like this couldn’t happen to them because they make what they feel to be better choices, rather than accept that life is random and unfair and little girls can disappear into thin air mere steps from their own door. Unable to find her own daughter, Saori begins defending other people’s children getting a job as a crossing guard to ensure they reach home safely while simultaneously frantic and afraid, handing out fliers to a largely disinterested populace ever hungry for novelty and excitement and embarrassed by her pain even as they continue to feed on it.

Missing screened as part of this year’s Toronto Japanese Film Festival.

Original trailer (English subtitles)

There are few things in life which cannot at least be improved by a full and frank apology. Sometimes that apology will need to go beyond a simple, if heart felt, “I’m Sorry” to truly make amends but as long as there’s a genuine desire to make things right, it can be done. Some people do, however, need help in navigating this complex series of culturally defined rituals which is where the enterprising hero of Nobuo Mizuta’s The Apology King (謝罪の王様, Shazai no Ousama), Ryoro Kurojima (Sadao Abe), comes in. As head of the Tokyo Apology Centre, Kurojima is on hand to save the needy who find themselves requiring extrication from all kinds of sticky situations such as accidentally getting sold into prostitution by the yakuza or causing small diplomatic incidents with a tiny yet very angry foreign country.

There are few things in life which cannot at least be improved by a full and frank apology. Sometimes that apology will need to go beyond a simple, if heart felt, “I’m Sorry” to truly make amends but as long as there’s a genuine desire to make things right, it can be done. Some people do, however, need help in navigating this complex series of culturally defined rituals which is where the enterprising hero of Nobuo Mizuta’s The Apology King (謝罪の王様, Shazai no Ousama), Ryoro Kurojima (Sadao Abe), comes in. As head of the Tokyo Apology Centre, Kurojima is on hand to save the needy who find themselves requiring extrication from all kinds of sticky situations such as accidentally getting sold into prostitution by the yakuza or causing small diplomatic incidents with a tiny yet very angry foreign country. How exactly do you lose a war? It’s not as if you can simply telephone your opponents and say “so sorry, I’m a little busy today so perhaps we could agree not to kill each other for bit? Talk later, tata.” The Emperor in August examines the last few days in the summer of 1945 as Japan attempts to convince itself to end the conflict. Previously recounted by Kihachi Okamoto in 1967 under the title Japan’s Longest Day, The Emperor in August (日本のいちばん長い日, Nihon no Ichiban Nagai Hi) proves that stately events are not always as gracefully carried off as they may appear on the surface.

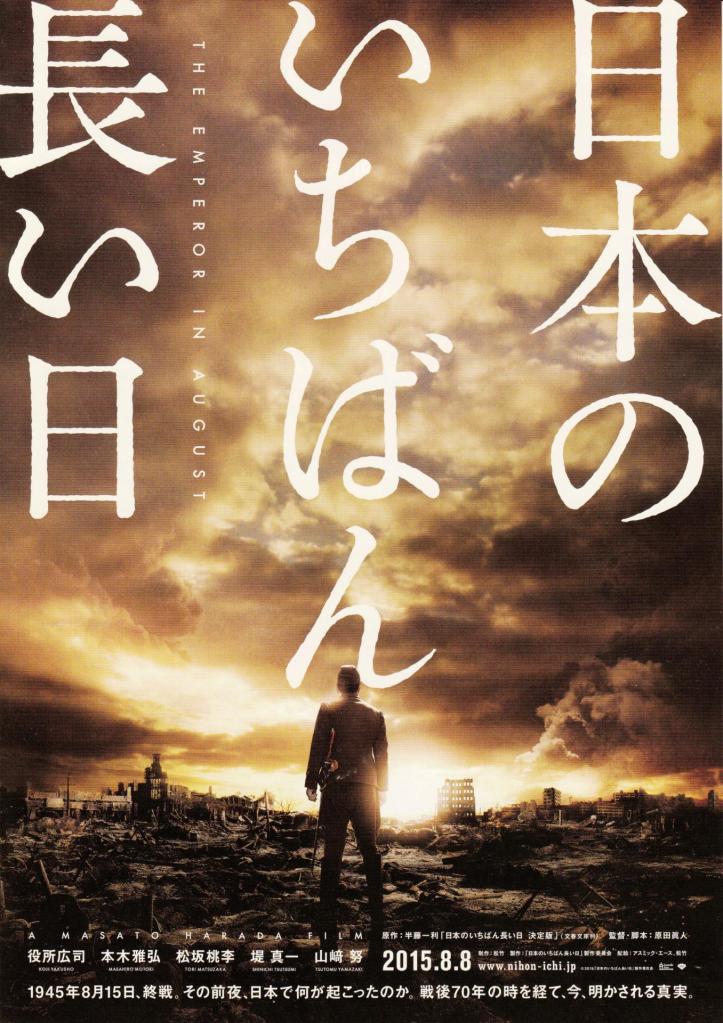

How exactly do you lose a war? It’s not as if you can simply telephone your opponents and say “so sorry, I’m a little busy today so perhaps we could agree not to kill each other for bit? Talk later, tata.” The Emperor in August examines the last few days in the summer of 1945 as Japan attempts to convince itself to end the conflict. Previously recounted by Kihachi Okamoto in 1967 under the title Japan’s Longest Day, The Emperor in August (日本のいちばん長い日, Nihon no Ichiban Nagai Hi) proves that stately events are not always as gracefully carried off as they may appear on the surface.