Lee Jang-ho returned to filmmaking after a short hiatus having been temporarily banned for the possession of marijuana in 1980 with a fresh new approach focussing on the social issues of the day as Korea found itself in the midst of confusion following the assassination of president Park Chung-hee. Though many hoped for a new era of long-awaited democratisation, those hopes were soon dashed by another military coup and the continuation of oppressive dictatorship under Chun Doo-hwan. During his time away from the film industry, Lee had run a bar with his mother and it was there that he became more acquainted with the struggles of ordinary people.

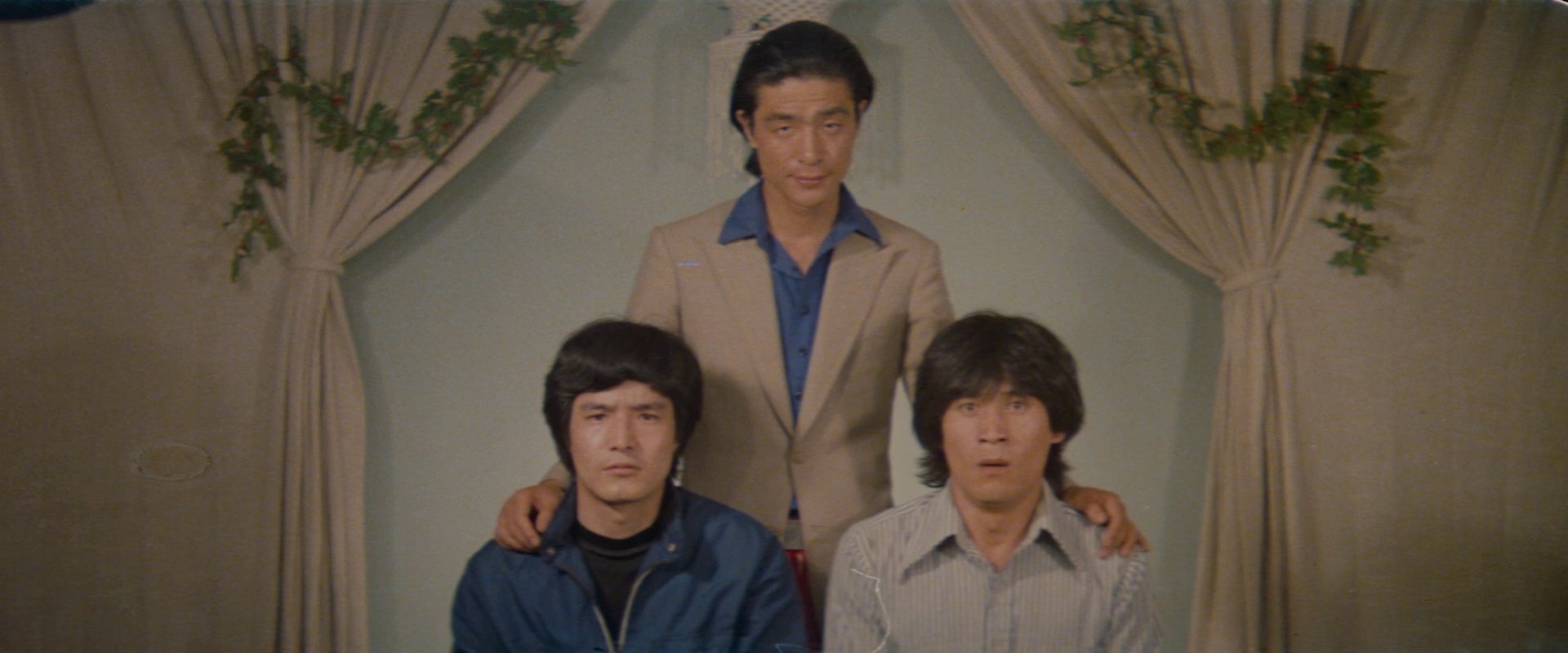

Adapted from a novel by Choi In-name, A Fine, Windy Day (바람 불어 좋은 날, Barambuleo Joheun Nal) follows three young men who have migrated from the countryside to Seoul in wider movement of urban migration. The sister of one of the men who later joins them remarks that there are no young people left in the countryside and her brother agrees that there is no longer any future in farming. Yet as the opening of the film makes clear in its idealised vision of pastoral life, it is really the expansion of the cities which has displaced the men and destroyed the natural habitats they once inhabited. The film often aligns the three with stray dogs who’ve come scavenging in the city because they can no longer survive in their rural hometowns.

“It’s as if I’ve been taking a beating for two years straight from some invisible person” delivery boy Deokbae (Ahn Sung-ki) remarks during the film’s conclusion of his life in Seoul which does indeed seem to have been one long and bloody battle that had forced him into submission. As he tells equally naive country boy Suntae, he never stuttered before he came to the city but is now cowed and anxious all too aware of how the native Seoulites treat men like him. Daughter of a wealthy family, Myung-hee (Yu Ji-in) drives her own car around town, knocking over school children and not even bothering to stop until challenged by Deokbae for ruining the food he was currently in the middle of delivering. He later gets a telling off from his boss and his pay docked while she wraps her expensive scarf around his neck and promises to send compensation money to the restaurant where he works.

Deokbae knows that Myung-hee is merely playing with him, her strangely childish glee like a little boy pulling the wings off a fly, yet he continues to associate with her. She laughs at him when he sits on the floor instead of the sofa after she ordered from the restaurant to get him to come to her house, and then tries to kiss him before becoming angry and pushing him away. Her posh friends later invade the restaurant and are drunk and rowdy, refusing to leave until a fight develops and they’re all carted off to the police.

But it’s only one of several degradations the men suffer at the hands of a new aristocracy not so different from the feudal elite. Chunsik (Lee Yeong-ho) works at a hairdresser’s where he is smitten with the pretty stylish Miss Yu (Kim Bo-yeon) who is being more or less sold by her ambitious boss and thereafter coerced into a compensated relationship with a sleazy businessman, Mr Kim, who was himself once a country boy but got rich quick through property speculation having cheated the old man who appeared in the film’s opening out of his ancestral land which has since been turned into the half-built slum inhabited by the three men. He is about to open a new shopping centre where the barber hopes to gain a prime position thanks to providing access to Miss Yu. The old man rails around the town demanding the return of his land, decrying that heaven will punish Mr Kim for what he’s done, and finally commits suicide in the newly completed building almost as it he were cursing it.

The old man’s body is laid out on the last remaining stretched field where a shamanistic funeral song plays as a lament for the now ruined pastoral idyll which has been taken from each of the men and replaced with internecine capitalism in which wealth comes at the exchange of humanity. At the Chinese restaurant where Deokbae works, the wife of the dying boss had been carrying on an affair with the manager whom she hopes to marry once her husband has gone, while he expects to take over the shop though as is later revealed he is already married with children and technically performing a long con on her. The third man, Gilnam (Kim Seong-chan), works in a motel while saving money to open a hotel of his own but unwisely gives his savings to his girlfriend who runs off with them leaving him with nothing. He is then drafted for military service, receiving another blow from the contemporary Korea.

The man who spars with Deokbae who takes up boxing after his altercation with the rich kids is also wearing a shirt that reads “Korea” on the back and we watch as he is mercilessly beaten but this time refusing to give up reflecting only that he’s learned how to take a hit which is it seems the only way to survive in the Seoul of the early 1980s. The tone that Lee lands on is however one of playful irony, particularly in the meta-quality of the closing narration along with its victory in defeat motif as Deokbae acknowledges the need to roll with the punches which is also a subversive admission of the futility of his situation in which it is simply impossible to resist the system. A lighthearted but also melancholy chronicle of the feudal legacy repurposed for a capitalist era the film encapsulates itself in its bizarre disco scene as a confused Deokbae dances like a shaman, forever a country boy lost in an increasingly soulless and capitalistic society.