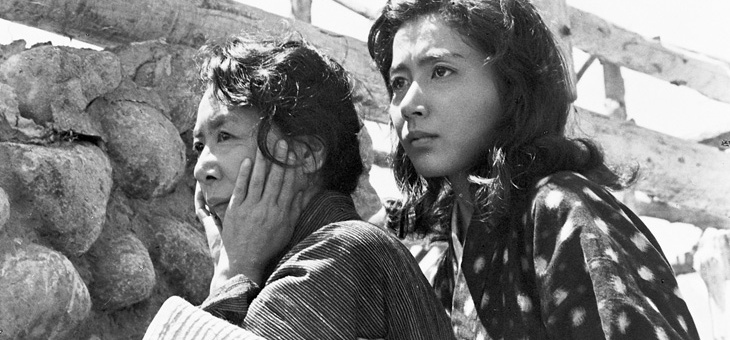

Patriarchal feudalism destroys not only the life of an innocent young woman but all of those around her in Keisuke Kinoshita’s embittered romantic melodrama Immortal Love (永遠の人, Eien no Hito). Scored to the impassioned beat of an incongruous flamenco and spanning almost thirty years of turbulent history from the tightening years of militarism to Anpo protests, Immortal Love finds its heroine imprisoned by the system within which she was raised but determining to free her children from the legacy of feudalism even while knowing that she traps herself in her intense resentment towards her husband and everything he represents.

Heibei (Tatsuya Nakadai), the wealthy son of the village chief, returns home from military service in Manchuria after sustaining an injury that will leave him walking with crutches for the rest of his life. Though his father tells him that his is an honourable discharge and has organised a small parade complete with flag waving and a band to greet him, it’s obvious that Heibei feels ashamed to have returned home wounded and is unhappy that his father has made such a fuss. He’s doubly unhappy at his welcome home party on hearing the gossip that local beauty Sadako (Hideko Takamine) is in love with farmer’s son Takashi (Keiji Sada) to whom Heibei has always felt inferior, something which is only exacerbated by the fact Takashi is also at the front and apparently acquitting himself well. Cruelly calling her over, he tells Sadako that he met Takashi at a field hospital but that he was about to go off to a big battle so could very well be dead.

Heibei’s true feelings, if you could call them that, remain unclear. Later, justifying himself, he claims that he really did care for Sadako and that all of his subsequent “immoral” acts were committed out of a love he was ill equipped to express, but that first night at the party it seems obvious that he only wants her because he knows she is Takashi’s. He tries to assault her when she is massaging his wounded leg, attempts to court her, and then finally resorts to rape with the help of his father who keeps Sadako’s dad occupied by forcing him to drink sake as his guest while making veiled threats about the status of his tenancy. Heibei had made a formal proposal which Sadako was about to turn down, further humiliating him, despite the pressure he’d piled on by threatening to throw Takashi’s brother off his land and potentially kicking her family off theirs too. By raping her and tricking her father into agreeing to the marriage he forces her to accept, wielding his feudal privilege like a weapon.

Shortly before the marriage, Takashi returns on leave, a heroic soldier painted in glory. He too is resentful and heartbroken to learn that Sadako is to marry to Heibei, eventually hearing the truth of it from his brother. Sadako tries to kill herself rather than be forced into marriage with her rapist, and avoids seeing Takashi in thinking she is now “impure” and can no longer be his wife. Takashi assures her she is wrong, and that even if Heibei thinks he has “stolen” her in taking her by force, he can simply take her back. He proposes they elope, but fails to turn up, leaving Sadako standing sadly at the roadside until her father arrives with a letter explaining that Takashi has reconsidered and advises her to accept a life of material comfort as Heibei’s wife rather than one of hardship with him.

Forced to marry the man who raped her, Sadako lives in quiet resentment, bearing three children the first of which she struggles to love because he is the result of the rape which condemned her to her present life of misery. Years later, Sadako learns that Takashi married too when his wife Tomoko (Nobuko Otowa) is evacuated to the village to stay with his brother. Heibei, ever cruel, offers Tomoko a job as a household servant, revelling in the idea that Takashi’s first love and current wife are both under his roof, telling her all about their strange romantic history and setting her at odds with Sadako whom she too resents knowing that her husband has never loved her because he can’t give up on his first love. A twisted bond arises between Heibei and Tomoko, united in resentment of Takashi and Sadako, but Heibei eventually tries to rape her too, once again trying to take what Takashi has, or possibly destroy it.

Despite her despair and loathing for her husband, Sadako tries to rise above it and always makes a point of treating Tomoko with respect and kindness even when she is cruel. Later on the road, she tells her not to worry, that what she grieves isn’t Takashi but the life she lived before. Heibei is perhaps also a victim of the system, his masculinity undermined by his brash father while his sense of inferiority is exacerbated by his disability, but he is also innately cruel and selfish. There’s strange perversion in the act of healing which closes the film in that it forces Sadako to ask for an apology from Heibei, the man who raped her and ruined her life, for using his abuse as an “excuse” to go on hating him all these long years. Heibei characteristically paints himself as the victim, branding Sadako a cold and unfeeling woman, wondering who will look after him now that he has been abandoned by all his children. He tells her that his feelings were sincere even if his acts were immoral, implicitly blaming her for the abuse that he inflicted, but Sadako merely accuses him of romanticising the past in trying to justify this internecine bid for vengeance that ruined the lives of at least four people as a frustrated love story.

“You and I may never be reconciled until one of us dies” Heibei admits, while Sadako tearfully tells a dying Takashi that it’s not too late for her to try to be happy. Tomoko was able to reconcile with her son and apparently lived out the last of her days in contentment. Naoko (Yukiko Fuji), Sadako’s daughter, eventually married Takashi’s son Yutaka (Akira Ishihama), breaking with the past both in rejecting the feudal class structure within which she was raised in marrying a working class man, and the patriarchal in ignoring her cruel father’s authority. A kind of healing has been achieved, freeing the younger generation from the cursed family legacy which claims that their ancestral wealth was gained by a literal betrayal of thousands of peasant farmers at the time of the siege of Osaka in 1615. The corruption of the war and a culture of hypermasculinty is visited on Sadako in the violent trauma of the rape, an event which echoes through not only her life but perhaps her children’s too. It is not she who should be asking for forgiveness, but she does perhaps begin to find it in herself, in making a kind of peace with the past which at least cuts the cord, allowing the younger generation to escape the net of feudal oppression for a brighter, freer, post-war future.

Immortal Love is available to stream in the US via the Criterion Channel.

Original trailer (no subtitles)