Yoshitaro Nomura is most closely associated with the thriller and particularly with its lower end as a purveyor of B-movie noir, yet look a little closer and his films are perhaps not really about crime at all but about the complicated relationships between people in the ever changing post-war society. Just as Stakeout is really about a policeman’s marriage, Tokyo Bay (東京湾, Tokyowan) is less concerned with the radiating corruption of the smuggling ring at its centre than with frustrated male friendship and the wartime legacy.

Opening with an aerial pan over post-war Tokyo, a title card informs us that this is just one frame in the “intense struggle for existence” in a city of 10 million before we arrive at the titular bay and a boat which is presumably carrying drugs later passed from one hand to another. The fixer, Takeyama (Kei Sato), talks to a man in a car and instructs him to be in front of the Taiyo building before 10am to pick up a golf bag from his contact. Gazing up at a post-war construction site, however, the man, Saeki (Jun Hamamura), is shot in the head and killed by a bullet piercing the roof of his car, Nomura suddenly switching to a disorientating POV shot as he twists in a sudden death spiral.

As it turns out, Saeki was a plant, an undercover cop with the drugs squad sent to expose the smuggling ring the shadowy owners of which will predictably turn out to have Chinese connections in another echo of post-war cinema’s continuing Sinophobia. Two officers are assigned to the case, the young and earnest Akine (Jiro Ishizaki), and the veteran Sumikawa (Ko Nishimura) who acts largely on a series of inexplicable policeman’s hunches. Their major lead, however, comes as a stroke either of dumb luck or dark fate as Sumikawa, dodging into a dodgy mahjong parlour while tailing Takeyama, runs into an old army buddy, Inoue (Isao Tamagawa), who just happens to be a left-handed sniper perfectly matching the profile of the man they’ve been looking for.

While Sumikawa keeps tabs on his old friend, somehow feeling he has something to do with all this but ambivalent in his torn responsibilities, Akine travels to Inoue’s hometown of Onomichi and sympathetically concludes that he was merely “rather unfortunate”. His life derailed by the war, Inoue returned to discover the girl he hoped to marry had married someone else. Giving evidence at Inoue’s trial for pulling a knife on her husband, the young woman remarks that she never promised him anything and did not consider their relationship to be serious, merely treating him with the politeness due to someone about to leave for war. In any case, she asks, even if she had been in love and intended to wait for him, as an orphaned woman there were only two choices open to her to survive, marriage or sex work, what else could she have done?

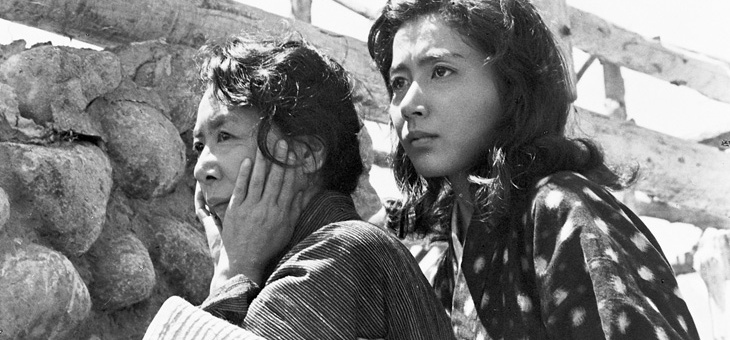

Back in Tokyo, Sumikawa begins to catch up with his old friend, realising that his romantic disappointment set him on a dark course of bad relationships and a drift towards crime but that he seems to have turned himself around. He is now happily married to a woman he describes as “simple” who seems devoted to him and if he did this, he did it to start again. His one last job intended to take him back to Onomichi, a pleasant coastal town the bay of which he describes as far more beautiful than that of the grimy, industrial Tokyo and largely untouched by urban corruption. Sumikawa feels himself torn, not least on account of the debt that exists between the two men because Inoue once saved his life, but also knowing that he may have to arrest this man and destroy his attempt to return to a more innocent world leaving his wife alone. Disapproving of the nascent relationship between his younger sister Yukiko (Hiromi Sakaki) and his partner, Sumikawa worries Akine may be becoming the kind of man who cares more for making an arrest than friendship, a conflict presumably weighing on his mind, even as he agrees he’s a good man and a good police officer. Yukiko meanwhile fires back that Sumikawa’s wife left him not because he is a policeman but because he is selfish and arrogant, and more to the point incapable of understanding a woman’s feelings.

Nevertheless, he’s acutely aware of the effect his actions or inactions may have on Inoue’s wife Yoshiko (Kyoko Aoi), especially as it’s suggested she may need a degree of looking after. Inoue, careful to admit nothing, reveals that the man who carried out the hit may not have known he was killing a police officer but may have assumed the target was fair game being, like themselves, a denizen of the underworld. Largely a MacGuffin, the smuggling ring is not as important as one might assume, the two men locked into a cycle of guilt and retribution each marked by wartime trauma and in a sense unable to claim their place in the post-war society. Twin betrayals lead to a fateful, train-bound showdown shot with fraught claustrophobia as each man engages in an intense struggle for his survival but also perhaps already defeated in a shared sense of fatalistic nihilism. Trekking through the half-constructed streets of the post-war city with shaky handheld Nomura hints at the radiating corruption exemplified by the growth of the trade in drugs, but perhaps one corruption is merely the result of another which may in turn be far less easy to cure.

Masahiro Shinoda’s first film for Shochiku,

Masahiro Shinoda’s first film for Shochiku,