Yoshitaro Nomura is best known for his crime films often adapted from the novels of Seicho Matsumoto though his filmography was in fact much wider than many give him credit for. Even so, 1980’s Writhing Tongue (震える舌, Furueru Shita) may seem an odd entry adapted from the semi-autobiographical novel by Taku Miki exploring the psychological torment of the parents of a little girl who contracts tetanus while innocently playing near a pond. Like the following year’s Call From Darkness, Nomura’s intense drama eventually shifts into the realms of psychedelia in the father’s strange fever dreams while lending this harrowing tale of medical desperation the tones of supernatural horror.

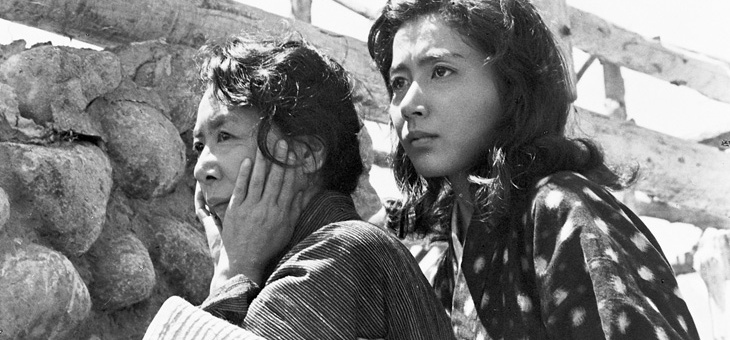

When five-year-old Masako (Mayuko Wakamori) seems to be under the weather, her mother Kunie (Yukiyo Toake) takes her to the hospital but is told by the disinterested doctor that she simply has a cold. This is a little surprising seeing as Masako’s main complaint is she that cannot open her jaw, probably the best-known indication of tetanus infection which is after all not so rare as to be easily missed by a medical professional. Still worried, Kunie keeps taking her daughter back especially once her leg becomes twisted leaving her struggling to walk, but the doctors that she sees don’t really listen to her, even implying that Masako is having some kind of early life breakdown because her father, Akira (Tsunehiko Watase), is overly strict with her. This may be in part because Masako, perhaps in fear, keeps saying that she could walk or open her mouth if she wanted but is choosing not to. In any case the true diagnosis is only discovered after the couple manage to get a referral from a friend to a larger hospital where the veteran professor (Jukichi Uno) quickly overrules his junior’s lack of concern to have Masako admitted right away later explaining that tetanus is a difficult disease to treat and unfortunately has a high mortality rate.

The treatment dictates that Masako receive as little stimulation as possible, lying in an entirely dark room with minimal noise so as to avoid the violent convulsions that accompany overstimulation and cause her to bite her tongue. As Akira later puts it, all they can do is wait trapped alone in the dark and tiny room with Masako entirely powerless to help her and with little knowledge of what exactly is going on. Meanwhile, despite having been repeatedly reassured that the disease is not transmitted in that way, Akira is convinced he may have contracted tetanus after being bitten by Masako while trying to prise open her jaw. Kunie too later worries that she also has tetanus, the pair of them sucked into a claustrophobic world of isolation and medical paranoia in which they are unable to sleep or find relief while watching over their daughter.

Some time later, Akira begins having bizarre psychedelic dreams recalling the time when he too was hospitalised as a child having contracted blood poisoning, remembering his own fear and confusion on being forced to endure “red injections” which he feared would “turn the whole world red” while the hieroglyphics he and his wife have been using to record Masako’s seizures dance before his eyes. He dreams of crows and blood rain while Kunie goes quietly out of her mind at one point threatening the sympathetic Doctor Nose (Ryoko Nakano) thinking it might be kinder to stop the treatment and let her daughter escape this excruciating pain. The utter powerless with which the couple are faced is filled with almost supernatural dread as if Masako had been possessed by some terrible evil, Akira attempting to speak directly to the bacteria asking them why it is they’re trying to colonise his daughter’s body and if they realise that in killing her they kill themselves too.

“It’s odd, our life. It’s so fragile” Akira sighs. All of this happened because of a tiny cut on a little girl’s finger the kind not even quite worth putting a plaster on and yet she might die from it. Convinced they all may die, Akira tells his wife to go home and put their affairs in order while she is so traumatised that she becomes unable to re-enter the room paralysed not out of physical disability but mental anguish. When Masako’s condition finally improves, Akira can hear his daughter crying that she’s frightened reminding him that he can never really understand the way she suffered through this terrible disease while all he could do was watch. A truly harrowing depiction of the hellish psychological torment of serious illness, Nomura’s occasionally psychedelic drama lays bare the fragility of life in a world of constant and unexpected dangers.

Trailer (no subtitles)