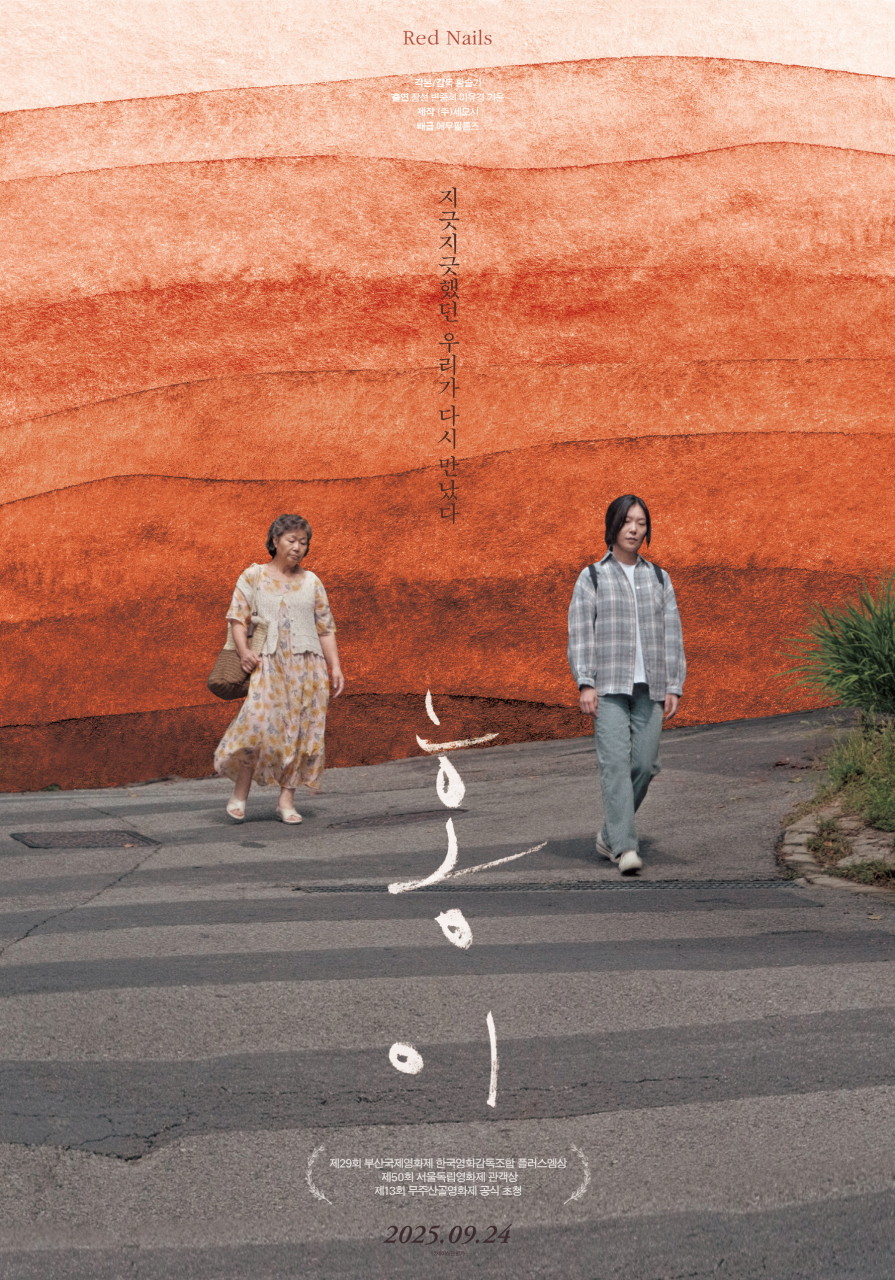

A not quite middle-aged woman watches as her mother takes an aerobics class with other similarly aged people at a nursing home. The attendant turns to her and remarks that it can’t have been an easy decision, leading us to think that she has reluctantly decided her mother may be better off living where she can be properly looked after. But Hong (Jang Sun) has actually arrived to take her mother home. Not because she’s had a change of heart, and not exactly because she’s having a hard time and can’t afford to pay for the home any more, but because she’s realised her estranged mother’s a cash cow and the only one she has left to tap.

Hwang Seul-gi’s complex drama Red Nails (홍이, Hong-i) never shies away from its heroine’s flaws even if it tries its best to empathise with her. Hong is clearly irresponsible with money. The piled up boxes in her living room hint that she may have fallen victim to a multi-level marketing scam, but whatever the root causes are, she’s pretty much bankrupt with the bailiffs about to be sent in to seize her goods due to her phenomenally large debts. Even so, we later see her going on shopping sprees as if she were trying to fill some sort of void through guilty consumerism that is really just punishing herself by making her situation even worse.

Hong’s borrowed money from an ex-boyfriend who has since married someone else but continues to sleep with her while badgering Hong for his money back, claiming his wife’ll throw a fit if he doesn’t get it. Meanwhile, she’s engaged in a fantasy romance with a man from an app, Jin-woo, whom she misleads about her financial circumstances and later uses when she needs a free ride. Hong has a habit of taking advantage of people, including her mother’s old friend Hae-joo who agrees to watch her in the day. Hong often messes her around, staying out late without calling and just expecting Hae-joo is figure something out. Hae-joo eventually confronts her about her unreasonable behaviour while taking advantage of her free labour, but Hong tries to give her money as if that was the problem. Hae-joo is insulted, and bringing money into the equation only threatens to change the nature of the relationship. It makes Hae-joo feel cheap and used when she had been doing this as a friend because she cared about Seo-hee.

Seo-hee, meanwhile, seems ambivalent about her new living standards and, at times, berates Hong complaining that she wishes she’d never been born. It’s not clear what happened in Hong’s childhood, but they evidently did not get on and still don’t now. Seo-hee wants to go home, complaining that there’s a thief in the house though whether or not she knows that Hong has been dipping into her savings to pay off her debts, she’s still aware that she brought home because she needed money rather than companionship.

But then Hong is also lonely, and her romance with Jin-woo is an attempt to escape her disappointing circumstances. Her ex suggests she once dreamed of becoming a teacher, but is currently teaching a literacy class for a group of older woman at a local institute where she also cleans the toilets. She also has a second job directing traffic at a construction site where the foreman hates her, docking her pay for neglecting her duties by using her phone while on the job. She cannot her escape her debts through any legitimate means, though that hardly justifies stealing from her mother.

Even so, it appears that on some level Hong wanted comfort and companionship along with her mother’s approval. As they live together, they begin to draw closer but at the same time it’s clear that they remember things differently, though whether Hong is right to blame Seo-hee’s dementia or has misremembered herself is destined to be an eternal mystery. Hong tries to fulfil her mother’s dream of lighting sparklers, but the pair are yelled by some kind of environmental officer and forced to put them out. Hong looks on forlornly as the glow fades away as if symbolising the flame going out of the relationship between the two women. Despite their growing closeness, there are some things that it seems can never really be made up and all Hong really has is a frustrated memory of a longed-for closeness that can never really be.

Red Nails screened as part of this year’s London Korean Film Festival.

Trailer (no subtitles)