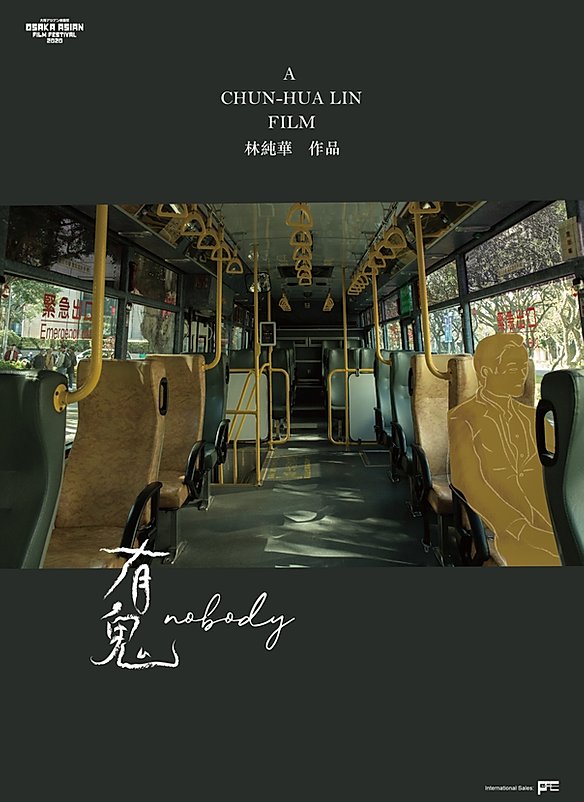

“Everyone has secrets that they don’t want others to know” according to the hero of Lin Chun-hua’s Nobody (有鬼, Yǒu Guǐ). He is indeed quite correct, everyone is in one sense or another living a lie, pretending to be something they’re not and often for quite complicated reasons which make them unhappy but convince them that their unhappiness is a kind of victory. Yet, there is no true connection without vulnerability and the sharing of a secret can be the most profound of intimacies, even if the connection itself is, perhaps wilfully, misunderstood by others.

Credited only as “Weirdo” (Jian fu-sang), an old man lives in an illegally occupied attic space on top of an old-fashioned apartment building that he now finds difficult navigate due to his increasing mobility issues. For unclear reasons, he spends his days riding the bus to the hospital but making sure to spit somewhere along the journey, a habit which has made him the bane of bus drivers across the city. Thoroughly fed up, one particular driver decides to throw Weirdo off his bus by force despite his old age and relative frailty, causing him to sustain an injury to his head.

When he gets back to his apartment, Weirdo finds an unexpected intruder – teenager Zhenzhen (Wu Ya-ruo) who has snuck in in order to spy on the apartment opposite where her father meets his mistress. Zhenzhen is from a wealthy though conservative home where her mother, Yuping (Huang Jie-fe), is the perfect housewife but makes a point of prioritising her husband and son, leaving Zhenzhen feeling innately inferior simply for being female. Determined to be allowed to use the apartment to spy on her dad, Zhenzhen starts following Weirdo around, mostly trying to bully him into submission but Weirdo treats her the way he treats everyone else, simply ignoring her as if she didn’t exist.

The original Chinese title means something more like “haunted” or more literally “there are ghosts” and in some senses it’s tempting to think of Weirdo as a ghost himself as he deliberately attempts to walk through the world as if he existed in a different plane. He is however haunted by lost love and a terrible sense of guilt that keeps him alone in his attic dressing the same way he dressed forty years previously though his hands are now too weak to be able to tie his tie. And then there are those secrets, things he feels obliged hide in the most literal of ways because others simply wouldn’t understand.

What Zhenzhen discovers is that her family is full of secrets, but exposing them might cause more harm than good. She videos her father with another woman intending to expose him to her mother, but Weirdo tries to warn her that she’s the one that will probably end up hurt if she tries to use other people’s secrets against them. On the surface her family is a vision of upper-middleclass respectability, but her father’s having an affair, her mother is desperately unhappy, and her golden boy brother has secrets of his own. Challenged, Zhenzhen’s father resents her intrusion and points out that he provides for them as if his family life is just for show while he satisfies his desires outside of it, shutting down his wife’s admiration for her sister’s career as a pop idol manager by reminding her that she has a husband, home, and children while her sister has “nothing” because she is a single career woman and in his view an unsuccessful one. Yuping meanwhile is a taut, repressed, and unfulfilled middle-aged housewife actively lashing out at her daughter while sweetly supporting her husband and son, but tries to exorcise her own desires by teaching piano on the side and finding unexpected pleasure in flirtatious banter with one of her sister’s handsome idol stars.

Nobody is exactly being honest, but it’s the way we live our lives because like it or not secrets are the lifeblood of civility but also an impermeable barrier to connection. Unable to bond with her prim and proper mother, Zhenzhen finds support from Weirdo who begins to open up despite knowing that Zhenzhen’s superficial niceness was only a ploy to get into the apartment, perhaps connecting with her sense of loneliness and betrayal as a young woman discovering that to one extent or another everyone lives a lie. Yet sharing the truth if only with one person can be its own kind of salvation, allowing youth and age to save each other from a world riddled with hypocrisy.

Nobody made its World Premiere as part of this year’s Osaka Asian Film Festival.

Original trailer (English / Traditional Chinese subtitles)