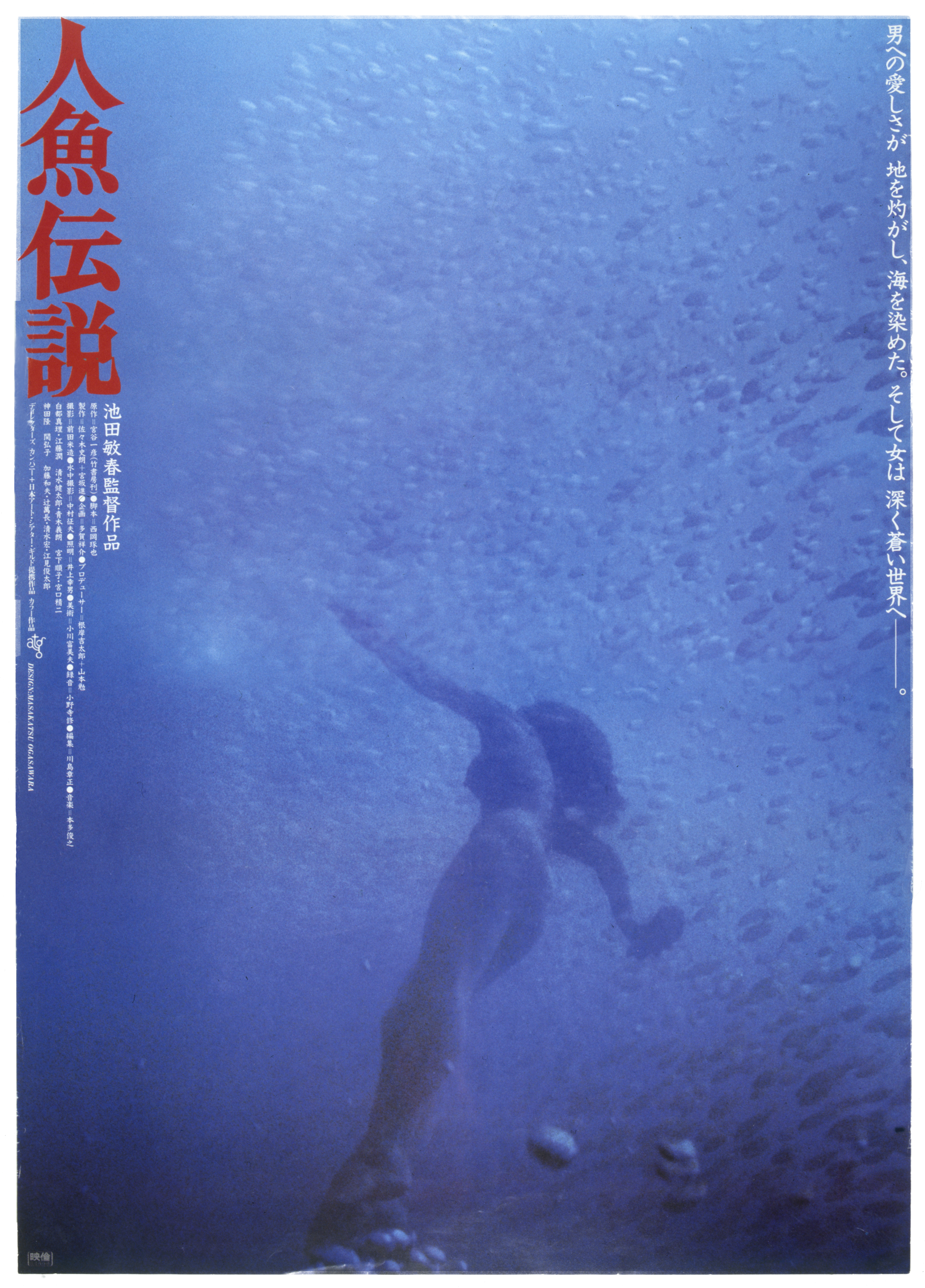

“Even if someone kills you, you wouldn’t die,” a drunken husband somewhat sarcastically replies having pledged to come back and haunt his wife if he died and she married a man who didn’t drink. His words take on a prophetic quality given that the heroine of Toshiharu Ikeda’s Mermaid Legend (人魚伝説, Ningyo Densetsu) takes on a quasi-supernatural quality as an embodiment of nature’s revenge after someone tries, and fails, to kill her having already killed her husband for witnessing their murder of another man who’d tried to resist their plans of buying up half the town to build a nuclear plant.

By the mid-1980s, Japan’s economy had fully recovered from post-war privation and was heading into an era of unprecedented prosperity which is to say that the coming of a power plant was not welcomed with the same degree of hope and excitement as it may have been in the 1950s when it was sold not only as a new source of employment for moribund small towns but an engine that would fuel the new post-war society. Several industrial scandals such as the Minamata disease had indeed left those in rural areas fearful of the consequences of entering a faustian pact with big business, which is one reason why the guys from Kinki Electric Power sell it as an amusement park project though even this has the locals wary not just of the disruption it will bring to their lives and potential ruin of their livelihoods which are dependent on the protection of the natural environment but that what is promised simply won’t be delivered. Fisherman Keisuke (Jun Eto) says as much when lamenting a previous aquaculture programme which didn’t pan out and caused lasting damage to marine life.

In any case, as others say there’s no money in going out to sea anymore and its clear that the old-fashioned, traditional way of life practiced by Keisuke and his newlywed wife Migiwa (Mari Shirato) is no longer sustainable. Migiwa is an abalone diver working without modern equipment but using heavy weights to dive deep enough to reach the shells. As such she’s dependent on her husband to pull her back up to the boat when she tugs the rope. She must put her life entirely in his hands though in truth, he does not seem to take his responsibility all that seriously. The couple bicker relentlessly and not even she really believes him when he says he witnessed a murder which might be understandable given the extent of his drinking. All of which is further evidence against her when she manages to escape from the assassination plot and runs straight to the nearest policeman who thanks her for turning herself in implying he believes she is responsible for Keisuke’s death.

The possible collusion of the policeman hints as a further sense of distrust in authority which has become far too close to corporate interests. Shady industrialist Miyamoto (Yoshiro Aoki) ropes in both the mayor and the head of the fishing association in his talks with Kinki Electric Power along with Shimogawa from the local tourist board who evidently opposes the plans as he is the man Keisuke witnesses being murdered. As Miyamoto says “sometimes your hands get a little dirty” though he never “directly” involves himself matters such as these. The situation is complicated by an unresolved love triangle between Miyamoto’s spineless son Shohei (Kentaro Shimizu), a sometime photographer, who is resentful of Keisuke and in love with Migiwa complaining that Keisuke always outdrinks him and gets the girl too hinting at his sense of wounded masculinity. Isolated by his class difference, he appears not to approve of his father’s actions but later does little to stop them and eventually sides with corporate interest over his feelings for Migiwa who in any case seems to have become more attached to Keisuke following his death which she vows to avenge.

There is there is something quite strange in the prophetical quality of Keisuke’s words also predicting the “black sweat” of the Jizo on the beach and the mystical storm which does eventually sweep everything clean destroying the signs for the new nuclear power plant already installed on the beach. In this way, Migiwa becomes a vengeful force of nature taking up arms against those who wilfully ravage and pollute the natural environment while damaging the lives of those who lived on its shores such as herself and Keisuke. She takes revenge not only for the murder of her husband by corrupt capitalists but against that corruption itself even as she laments that “no matter how many I kill, they just keep coming.” “Don’t worry, maybe all this was just a dream,” Keisuke once again prophetically intones though it’s difficult to know if it’s defeating the capitalist order that is a fantasy or the maintenance of the idealised rural life to which Migiwa seemingly finds her way back swimming into an unpolluted sea surrounded by the floating barrels of ama divers and clear blue skies, a creature of nature once again.

Mermaid Legend screened as part of this year’s JAPAN CUTS.

Until the later part of his career, Hideo Gosha had mostly been known for his violent action films centring on self destructive men who bore their sadnesses with macho restraint. During the 1980s, however, he began to explore a new side to his filmmaking with a string of female centred dramas focussing on the suffering of women which is largely caused by men walking the “manly way” of his earlier movies. Partly a response to his regular troupe of action stars ageing, Gosha’s new focus was also inspired by his failed marriage and difficult relationship with his daughter which convinced him that women can be just as devious and calculating as men. 1985’s Oar (櫂, Kai) is adapted from the novel by Tomiko Miyao – a writer Gosha particularly liked and identified with whose books also inspired

Until the later part of his career, Hideo Gosha had mostly been known for his violent action films centring on self destructive men who bore their sadnesses with macho restraint. During the 1980s, however, he began to explore a new side to his filmmaking with a string of female centred dramas focussing on the suffering of women which is largely caused by men walking the “manly way” of his earlier movies. Partly a response to his regular troupe of action stars ageing, Gosha’s new focus was also inspired by his failed marriage and difficult relationship with his daughter which convinced him that women can be just as devious and calculating as men. 1985’s Oar (櫂, Kai) is adapted from the novel by Tomiko Miyao – a writer Gosha particularly liked and identified with whose books also inspired