More or less out of fashion today, concept albums were all the rage back in the ‘70s and ‘80s but few of them ever made it to the big screen. Macoto Tezka’s The Legend of the Stardust Brothers (星くず兄弟の伝説, Hoshikuzu Kyodai no Densetsu), apparently drawing inspiration from The Who’s Tommy, is a rare exception though you’d be forgiven for never having heard of it seeing as it’s been mostly forgotten since receiving a decidedly frosty reception from critics on its 1985 release. Tezka would revisit the Stardust Brothers in 2016 with a Brand New Legend, but this now fully restored “director’s cut” distributed by Third Window Films who are also co-producing Tezka’s latest work – an adaptation of a manga by his legendary father Osamu Tezuka starring Fumi Nikaido, is the first opportunity many will have to reappraise the film in 34 years.

More or less out of fashion today, concept albums were all the rage back in the ‘70s and ‘80s but few of them ever made it to the big screen. Macoto Tezka’s The Legend of the Stardust Brothers (星くず兄弟の伝説, Hoshikuzu Kyodai no Densetsu), apparently drawing inspiration from The Who’s Tommy, is a rare exception though you’d be forgiven for never having heard of it seeing as it’s been mostly forgotten since receiving a decidedly frosty reception from critics on its 1985 release. Tezka would revisit the Stardust Brothers in 2016 with a Brand New Legend, but this now fully restored “director’s cut” distributed by Third Window Films who are also co-producing Tezka’s latest work – an adaptation of a manga by his legendary father Osamu Tezuka starring Fumi Nikaido, is the first opportunity many will have to reappraise the film in 34 years.

Inspired by an “imaginary soundtrack” composed by Haruo Chicada, The Legend of the Stardust Brothers concerns itself with aspiring musicians Shingo (Shingo Kubota) and Kan (Kazuhiro Takagi) who seem to have a healthy rivalry in the intense 1980s Japanese underground club scene. Their luck changes one day when they are each handed a card for a shady-looking management company, Atomic Promotion, where the manager, Minami (played by voice of the ’70s crooner Kiyohiko Ozaki), promises to make them stars beyond their wildest dreams but only on one condition – they have to form a band of two, or it’s no dice.

On their first arrival at Atomic Promotion, the boys are introduced to a young woman, Marimo (Kyoko Togawa) – an aspiring singer who has been repeatedly kicked out of Minami’s office because he doesn’t hire girls (seemingly a satirical reference to an all powerful agency controlling most of Japan’s A-list male idols). Kan comes to her rescue and, in a throwaway comment, casts himself as Urashima Taro rescuing the “turtle” from, in this case, belligerent security guards. It is tempting, in an impish sense, to read the rest of the ongoing tale as an extended retelling of the Urashima Taro myth as the boys find themselves catching a ride to another kingdom filled with untold wealth and unimaginable pleasure only to tire of their newfound luxury and discover that while they were trapped within a tiny champagne bubble of success other stars were also rising.

It is indeed the “plateau” of success which highlights the differences between the two guys and threatens to send each of them on different paths as they contemplate the demands of showbiz life. Shingo, an insecure rocker, begins to resent the presence of the ultra modern Kan whose punkish energy and zeitgeisty features have captured the hearts of the youth. Numbing the emptiness with drink and drugs, he dreams himself swallowed whole by his sworn brother before being chased by creepy zombies emerging from their human suits to suck whatever of his soul remains right out of him.

Bored by their fame, the boys resent the implication that their “stardom” comes only at the price of their artistic integrity. They long to break free of the corporate straightjacket which attempts to strip them of their individuality in order to replace it with a manufactured, marketable persona in another jab at the increasingly commodified idol world of the burgeoning bubble era. Meanwhile, the corporate machine moves on, mass media is exposed as yet another medium of propaganda with a (perhaps conflicted) Minami propositioned by a politician with a son keen to get into the business. Fearing the Stardust Brothers are too “vulgar”, the powers that be want a new face to sell the message of love and peace to the young, which sounds much more positive than it really is. The boys’ rival, Kaworu (visual kei pioneer Issay), is very much a figure of the age – an androgynous, Bowie-like counter culture personality who is in essence the face of entrenched privilege insidiously camouflaged to infiltrate alternative youth subculture.

Yet the political message is not perhaps the point so much as anarchic, absurdist fun. Perfectly in tune with lo-fi late punk / early New Wave sensibilities, Tezka’s script freewheels from one surreal set piece to another following the flow of Chicada’s expertly composed score which encapsulates the variety of the age while remaining absolutely of its time. Filled with youthful energy and true punk spirit, The Legend of the Stardust Brothers is the strange tale of the dust that stars are made on and its unexpected ability to find its way home even if it takes a little longer than expected.

The Legend of the Stardust Brothers is released on blu-ray later in the year courtesy of Third Window Films. It will also be screened as part of the 2019 Nippon Connection Film Festival on 1st June, 22.30.

Trailer (English subtitles)

Bonus:

Kiyohiko Ozaki’s 1971 hit Mata Au Hi Made

And its fantastic use in Isshin Inudo’s La Maison de Himiko

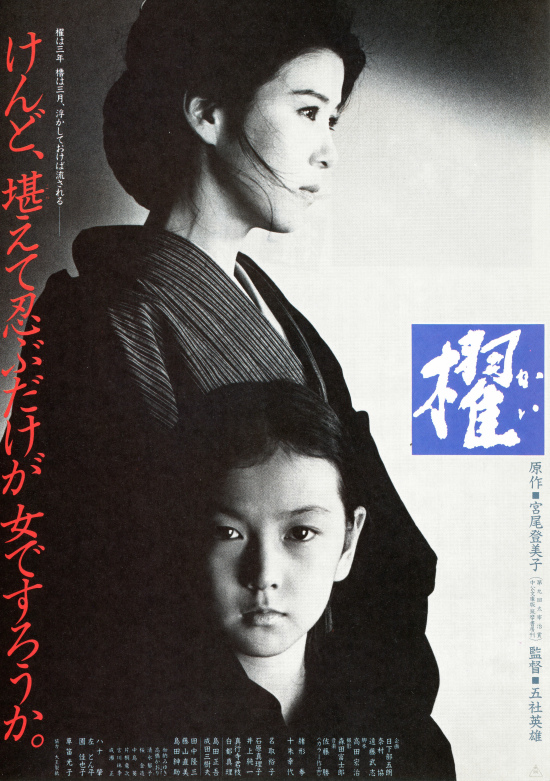

Until the later part of his career, Hideo Gosha had mostly been known for his violent action films centring on self destructive men who bore their sadnesses with macho restraint. During the 1980s, however, he began to explore a new side to his filmmaking with a string of female centred dramas focussing on the suffering of women which is largely caused by men walking the “manly way” of his earlier movies. Partly a response to his regular troupe of action stars ageing, Gosha’s new focus was also inspired by his failed marriage and difficult relationship with his daughter which convinced him that women can be just as devious and calculating as men. 1985’s Oar (櫂, Kai) is adapted from the novel by Tomiko Miyao – a writer Gosha particularly liked and identified with whose books also inspired

Until the later part of his career, Hideo Gosha had mostly been known for his violent action films centring on self destructive men who bore their sadnesses with macho restraint. During the 1980s, however, he began to explore a new side to his filmmaking with a string of female centred dramas focussing on the suffering of women which is largely caused by men walking the “manly way” of his earlier movies. Partly a response to his regular troupe of action stars ageing, Gosha’s new focus was also inspired by his failed marriage and difficult relationship with his daughter which convinced him that women can be just as devious and calculating as men. 1985’s Oar (櫂, Kai) is adapted from the novel by Tomiko Miyao – a writer Gosha particularly liked and identified with whose books also inspired