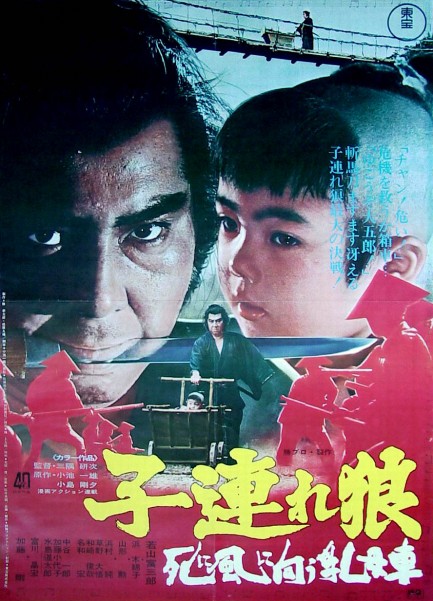

Ogami Itto (Tomisaburo Wakayama) and his (slightly less) young son Daigoro (Akihiro Tomikawa) are going to hell in a baby cart in this third instalment of the six film series, Lone Wolf and Cub: Baby Cart to Hades (子連れ狼 死に風に向う乳母車, Kozure Okami: Shinikazeni Mukau Ubaguruma). The former shogun executioner, framed for treason by the villainous Yagyu clan intent on assuming his position, is still on the “Demon’s Way”, seeking vengeance and the restoration of his clan’s honour with his toddler son safely ensconced within a bamboo cart which also holds its fair share of secrets. In the previous chapter, Baby Cart at the River Styx, Ogami’s stoic personality came to the fore as he showed that sometimes there is more strategic value to be found in avoiding a fight rather than charging into one where it isn’t necessary. Baby Cart to Hades will further test this element of his life philosophy as he finds himself bound onwards, seeking his redemption.

Ogami Itto (Tomisaburo Wakayama) and his (slightly less) young son Daigoro (Akihiro Tomikawa) are going to hell in a baby cart in this third instalment of the six film series, Lone Wolf and Cub: Baby Cart to Hades (子連れ狼 死に風に向う乳母車, Kozure Okami: Shinikazeni Mukau Ubaguruma). The former shogun executioner, framed for treason by the villainous Yagyu clan intent on assuming his position, is still on the “Demon’s Way”, seeking vengeance and the restoration of his clan’s honour with his toddler son safely ensconced within a bamboo cart which also holds its fair share of secrets. In the previous chapter, Baby Cart at the River Styx, Ogami’s stoic personality came to the fore as he showed that sometimes there is more strategic value to be found in avoiding a fight rather than charging into one where it isn’t necessary. Baby Cart to Hades will further test this element of his life philosophy as he finds himself bound onwards, seeking his redemption.

Neatly attaching Daigoro’s cart for towing, Ogami boards a boat which appears to be being followed by underwater ninjas, if the reeds he notices whilst using his sword as a mirror are anything to go by. Also on the boat is a distressed young woman, apparently on her way to be sold to a brothel. Diagoro takes pity on the girl and catches her tiny bundle of belongings when the loquacious middle man knocks them overboard. Later they all end up at the same inn where the unfortunate woman kills her procurer when he attempts to rape her (bad business decision as that would be). Daigoro takes pity on the woman once again and Ogami decides to help her, especially after he notices the wooden memorial tablet among her belongings. Rather than fight off the brothel running samurai who come to find her, Ogami agrees to undergo the torture which is the alternative to entering a brothel on the girl’s behalf.

In addition to saving a life from fear and suffering, Ogami’s forbearance also earns him the respect of the madam in question, Torizo (Yuko Hama), who has another job for him. Her older sister was raped at the court of their lord and subsequently committed suicide, she and her father would like him dead and are willing to pay for it. Amusingly enough, the corrupt lord in question also tries to hire Ogami for another assassination for which he will pay double, but Ogami is an honest man. This latest mission brings him closer to his fated battle with the Yagyu but the Demon’s Way is long and Ogami is not yet approaching its end.

Directed once again by Kenji Misumi, this third instalment is much less psychedelic and action packed than the preceding film but seems keener to explore more of Ogami’s world which is often cruel and unforgiving. An early scene in the film features a discussion between four mercenaries, one a fine samurai who refuses to associate too much with the other three who are of a much more earthy character. Caring only for women and sake, the three men live a life of banditry by another name, fleeting from one clan to another participating in parades to bulk out an otherwise lacking show of force. Kanbei (Go Kato), by contrast, at least has a consciousness of the “true samurai” and a conflicted heart when it comes to his way of life. Having been a loyal retainer and later betrayed by the very lord he was seeking to protect over a matter of protocol, he has lost sight of his place in the world but knows himself to be superior to these venal, dishonest, empty scabbards for hire.

These same three men then attempt to have some sport with a well to do mother and daughter unwisely travelling with a single attendant. After despatching their escort, the three rape the two women before turning to Kanbei for help to clear up the giant mess they’ve just made. Kanbei does indeed clear it up by killing the two women in the gentlest and most elegant way he can before instructing the three culprits to draw lots – one of them will have to die and take the blame for everything to avoid getting entangled with the local police. Neither Kanbei or Ogami arrive in time to save the two women, whose deaths are both a solution to their “defilement” and the means to coverup a crime, leaving two thirds of the perpetrators free to commit the same crime again further along the road. Female life is both cheap and worth a lot of money to the right people, though there are precious few willing to defend it as a matter of honour – even Ogami’s decision to help the young woman about to be sold against her will has more to do with the cosmic coincidence of her memorial tablet than a desire to defend a vulnerable girl in trouble.

Where the dying monologue in Baby Cart at the River Styx was about the elegance and nobility of killing, Baby Cart to Hades focuses on the nature of the “true samurai” as the similarly disenfranchised Kanbei and Ogami discuss the “proper” way of life and death. Kanbei, like Ogami, is a brave man who served his lord in his own way, only to accomplish his mission and be cast out by those who disagreed with his methods. Is it really wrong to fight to live, rather than prepare to die? Both men say no, but the conclusion that is reached is that a samurai can only live by death. Meeting for the first time, Kanbei requests a dual from Ogami, promising to care for his son if only he survives. Ogami agrees but later sheaths his sword and declares the fight a draw. He would rather not fight a man who appears to be his equal in every way and has no quarrel with him, though the two will meet again for an unavoidable showdown.

Misumi is more straightforward his direction save for a few expressionist scenes of the bright sunset and a dramatic switch to POV as a head is severed from its body and rolls away. Nevertheless the ninja antics become ever more impressive, as do Ogami’s methods of detecting them. Once again Ogami attracts the attention of a grateful woman in the person of Torizo who, in keeping with the previous two chapters, watches him push his baby cart away with tears in her eyes (all accompanied by the first appearance of a closing ballad in the series). There are a lot more bodies behind him now as Ogami strides away from a battlefield littered with corpses, yet he’s seemingly no closer to achieving his goal despite his brush with the Yagyu. The price of vengeance is increasing, but the Demon Way is long, and Ogami must follow it to its end, no matter where it leads.

Original trailer (German subtitles for captions only, NSFW)

Though he might not exactly be a household name outside of Japan, the late Yusaku Matsuda was one of the most important mainstream stars of the ‘70s and ‘80s. Had he not died at the tragically young age of 40 after refusing chemotherapy for bladder cancer to star in what would become his final film, Ridley Scott’s Black Rain, he’d undoubtedly have continued to move on from the action genre in which he’d made his name. No Grave For Us (俺達に墓はない, Oretachi ni Haka wa Nai) is fairly typical of the kinds of films he was making in the late ‘70s as he once again plays a cool, streetwise hoodlum mixed up in a crazy crime world where no one can be trusted.

Though he might not exactly be a household name outside of Japan, the late Yusaku Matsuda was one of the most important mainstream stars of the ‘70s and ‘80s. Had he not died at the tragically young age of 40 after refusing chemotherapy for bladder cancer to star in what would become his final film, Ridley Scott’s Black Rain, he’d undoubtedly have continued to move on from the action genre in which he’d made his name. No Grave For Us (俺達に墓はない, Oretachi ni Haka wa Nai) is fairly typical of the kinds of films he was making in the late ‘70s as he once again plays a cool, streetwise hoodlum mixed up in a crazy crime world where no one can be trusted. When it comes to the history of the yakuza movie, there are few titles as important or as influential both in Japan and the wider world than Kinji Fukasaku’s Battles Without Honour and Humanity (仁義なき戦い, Jingi Naki Tatakai). The first in what would become a series of similarly themed movies later known as The Yakuza Papers, Battles without Honour is a radical rebooting of the Japanese gangster movie. The English title is, infact, a literal translation of the Japanese which accounts for the slightly unnatural “and” rather than “or” where the “honour and humanity” are collected in a single Japanese word, “jingi”. Jingi is the ancient moral code by which old-style yakuza had abided and up to now the big studio gangster pictures had all depicted their yakuza as being honourable criminals. However, in Fukasaku’s reimagining of the gangster world this adherence to any kind of conventional morality was yet another casualty of Japan’s wartime defeat.

When it comes to the history of the yakuza movie, there are few titles as important or as influential both in Japan and the wider world than Kinji Fukasaku’s Battles Without Honour and Humanity (仁義なき戦い, Jingi Naki Tatakai). The first in what would become a series of similarly themed movies later known as The Yakuza Papers, Battles without Honour is a radical rebooting of the Japanese gangster movie. The English title is, infact, a literal translation of the Japanese which accounts for the slightly unnatural “and” rather than “or” where the “honour and humanity” are collected in a single Japanese word, “jingi”. Jingi is the ancient moral code by which old-style yakuza had abided and up to now the big studio gangster pictures had all depicted their yakuza as being honourable criminals. However, in Fukasaku’s reimagining of the gangster world this adherence to any kind of conventional morality was yet another casualty of Japan’s wartime defeat.