An actress gradually dissolves into her own image while wandering around Singapore in search of lost love in Ryu Murakami’s adaptation of his own novel, Raffles Hotel (ラッフルズホテル). Ryu Murakami may generally be more associated with the extreme revolving around transgressive sex and violence, yet like its namesake the film is a more elegant affair indulging in its own sense of mystery tinged with a melancholy eeriness in its heroine’s apparent instability.

Moeko (Miwako Fujitani) later admits that she is no longer an actress, and therefore no longer quite herself uncertain who it is she’s meant to be. In one sense perhaps that’s why she’s come to Singapore though in another it’s someone else she’s looking for though to begin with we may think she’s there to escape him, and it could be that too. “Maybe I’d feel better if he were,” she muses when her tour guide, Yuki (Masahiro Motoki), explains that there are no Japanese people near the gravestones she’s just been looking at trying to assure her that the man she’s seeking is not dead. She thinks she sees him everywhere, dropped into typical Singaporean scenes appearing as a durian seller or a man restoring a church while more literally haunted by the spectre of a friend who apparently died in Vietnam while covering the war. Kariya (Jinpachi Nezu) later tells her that he can’t forget the jungle while she asks to be taken there with him and travels to a mountain lodge where they hunt wild game with a crossbow.

Yuki first becomes worried about her when her hotel room is filled with orchids she claims are from Kariya only to discover she ordered them herself when the orchid house contacts the hotel to complain that the bill has not been paid. Even so, she continues to believe they are from the man she’s looking for, even going so far as to thank him for them as if unable to process the gap between her realities. We often see her looking at photos from her photo shoots, while she later complains to Kariya that she wants to laugh when she wants to laugh and cry when she wants to cry as if making plain her disconnection with her self and desire to reassert her own identity over those she is forced to assume as an actress.

This abstraction may also explain her words to Kariya that the sky is full of stars but that they are distant from each other and therefore the sky is only make-believe as if the image of Moeko that we see is only an illusion we’ve patched together from the various components available to us. It speaks of her alienation and loneliness, two qualities only deepened by her presence in an unfamiliar culture where she cannot speak the language. Acting as her guide, Yuki describes her as a polar opposite to his Singaporean girlfriend (Fawn Wong), the daughter of a wealthy family who is bold and confident, unafraid to chase her desires be they dancing or “Japanese hoods” as her father describes them.

Murakami semi-exoticises Singapore if at times ironically in homing in on the portraits of famous authors in the bar and a man who always seems to be banging away on a typewriter. He sends Moeko all around the island and follows her as she takes in tourist sights, tries durian, and watches Chinese opera but lends an eerie quality to her place within the hotel implying finally that her room has in a way swallowed her as her name is added to the list of famous people who have stayed there even as she remarks that she feels as if the ceiling fan has become sentient in its movement. In any case, the camera is something that she both fears and craves as it both gives and takes her identity. She tries to pick it up herself but points it without looking, finally asking Kariya to take her picture only to find herself becoming one with her image just as Kariya is reduced to shadow as if her very essence had dissipated into the atmosphere as symbolised in a swimming pool full of orchids. “Lost in a fantasy” she may be, but so are we, led astray by a vision of a woman we can never really see.

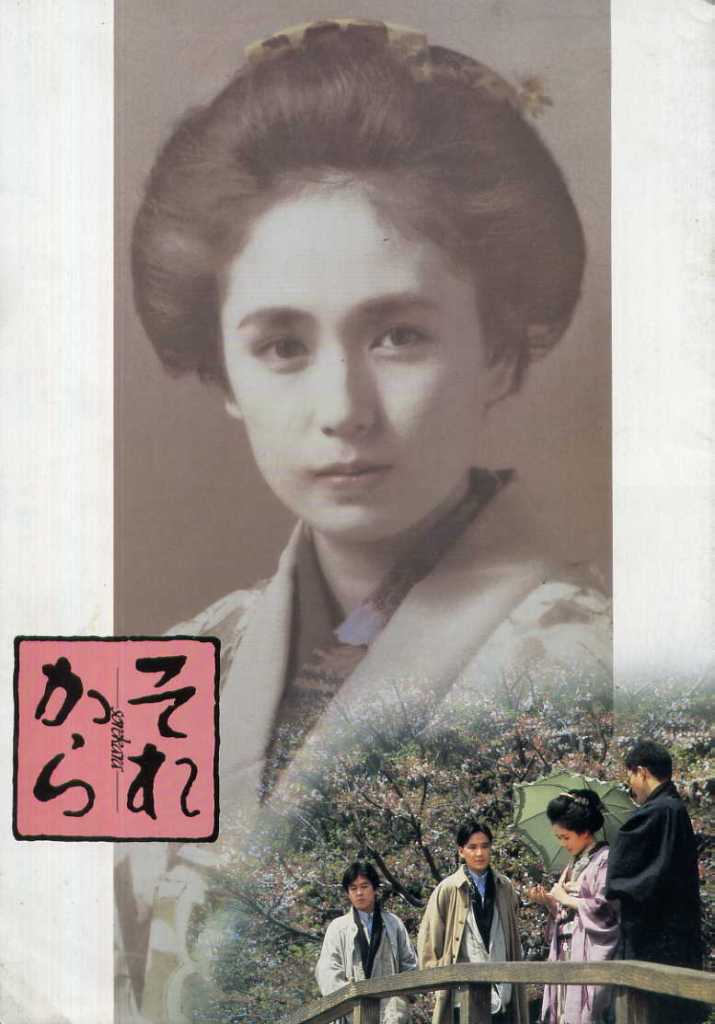

Yoshimitsu Morita had a long and varied career (even if it was packed into a relatively short time) which encompassed throwaway teen idol dramas and award winning art house movies but even so tackling one of the great novels by one of Japan’s most highly regarded authors might be thought an unusual move. Like a lot of his work, Natsume Soseki’s Sorekara (And Then…) deals with the massive culture clash which reverberated through Japan during the late Meiji era and, once again, he uses the idea of frustrated romance to explore the way in which the past and future often work against each other.

Yoshimitsu Morita had a long and varied career (even if it was packed into a relatively short time) which encompassed throwaway teen idol dramas and award winning art house movies but even so tackling one of the great novels by one of Japan’s most highly regarded authors might be thought an unusual move. Like a lot of his work, Natsume Soseki’s Sorekara (And Then…) deals with the massive culture clash which reverberated through Japan during the late Meiji era and, once again, he uses the idea of frustrated romance to explore the way in which the past and future often work against each other.