“We are all suffering from this Westernised lifestyle and way of thinking. They are not really meant for us,” according to a sympathetic doctor, played by the director himself, at the end of Lee Jang-ho’s erotic melodrama, Between the Knees (무릎과 무릎 사이, Muleupgwa muleupsai). The heroine does indeed find herself trapped between the Korea of the past and the modern society, but the film often seems confused in its central messages in its own use of the woman’s body as metaphor for that of the nation despoiled by foreign influence.

This is most obviously the implication of Ja-young’s (Lee Bo-hee) flashbacks in which she is quite clearly molested by her flute teacher who is a bearded white man. When her mother walks in on the abuse, she blames Ja-young beating her and shouting what we would assume to be unpleasant words branding her as a seductress though she is a clearly a child. As is later explained, Ja-young’s mother is carrying her own baggage in that her own mother was the mistress of a married man and fearful of the same fate befalling her daughter, she has brought her up with problematic notions of bodily purity that have caused Ja-young to develop a complex surrounding her sexuality in which she is unable to process her desires as a young woman.

She later says that through her “immoral behaviour and desire to sin” she has found “freedom” as if sexuality was her way of rebelling not only against her mother’s tyranny but social conservatism in general. However, she also characterises it as the extreme opposite, blaming her mother in insisting that her treatment of her has left her with no control at all over her sexuality. In the film’s problematic framing, she essentially allows herself to be raped by a series of men partly as an act of self-harm, partly as rebellion, and partly because she has no other way of permitting herself to satisfy her sexual desires. This is of course dangerous, portraying a woman who says no as one who is really saying yes but resisting out of shame, but there is also a completely paradoxical criticism of Korean men all of whom are rapists except for Ja-young’s sort of boyfriend Jo-bin (Ahn Sung-ki) who is so obsessed with traditional Korean culture that he has earned the nickname “antique”.

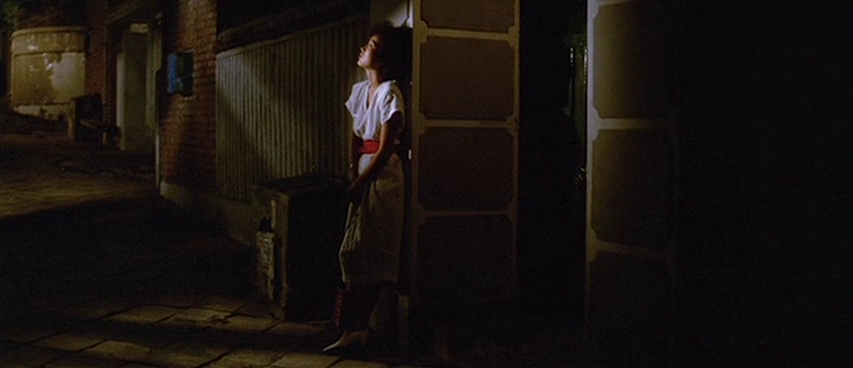

Jo-bin lives in a Korean-style home and spends his time playing the flute, training in traditional martial arts, and watching pansori in comparison to the pursuits of other young people such as Ja-young’s brother Ji-cheol who mimics Michael Jackson and spends all his time in discos. Towards the beginning of the film is seems that Ja-young will be torn between Jo-bin to whom she originally says “if you’re so old-fashioned I may have to run away with you” and an incredibly unpleasant fellow student who refuses to take no for an answer and in fact eventually rapes her during an expressionist rainstorm that violently awakens her sexuality. The battle then really becomes whether or not Ja-young will be able to accept it, despite the realisation that she is “no longer the kind of virtuous bride that Korean men expect.”

This hints at the pernicious double standard of the contemporary society in which men largely behave like animals, treating women like trophies to be conquered and then discarded while insisting on a “pure woman” for a wife. The discord in Ja-young’s home stems from patriarchal failure, not only that of the man that made her grandmother a mistress and not a wife, but her father’s in having fathered a child with a 17-year-old Korean War orphan he took into his home. Resentment over his betrayal has further embittered Ja-young’s mother and caused her to double down on her sexual conservatism while fiercely resenting her husband’s other daughter. Yet in the film’s final stretches, a degree of female solidarity arises between the women that largely excludes the father with Ja-young’s mother accepting Bo-young as another daughter and inviting her to live in their home now her still young mother has remarried.

Violent male sexuality also rears its head in a subplot in which a mute man who had developed feelings for Bo-young’s mother while they were being raised in the same orphanage attacks Ja-young’s father for ruining her life, as he undoubtedly did even if he tried to take at least some responsibility for his transgression. Bo-young later says that her mother hated the mute man and did not want to be in a relationship with him anyway, though he too it seems could not take no for an answer. In any case, it is only the traditionalist, Jo-bin, who is willing to accept Ja-young for who she is. He knows all of her ordeal and does not reject her for her sexually active past, rather scoffing when she had described sex as being a sin with the perhaps mistaken implication that such things were not regarded as taboo in the Korea of the past even as, paradoxically, it appears that Jo-bin is drawn to Ja-young’s old-fashioned modernity in rejecting his mother’s constant attempts to set him up with an arranged marriage.

Of course, all of this is also very much informed by the climate of contemporary Korean cinema which had descended into an era of softcore pornography deliberately supported by the Chun regime as part of a bread and circuses social policy designed to distract the people from their democratic desires. Lee opens with sexually charged closeup of Ja-young’s lips on her flute, a phallic symbol also present in Ja-young’s forbidden fantasises as she idly fondles it after hearing heavy breathing on the telephone and experiences another moment of sexual crisis. Perhaps that’s paradoxical itself in that it’s learning to play this Western instrument that has led to her corruption in an allegory for a nation’s pollution by Western culture. In any case, Lee seems to imply that sexuality can be an act of resistance towards oppressive social codes but is otherwise unsure if that represents liberation or merely another form of oppressing one’s self.