“This is my grand revenge against the world,” a frustrated civil servant insists while watching a giant avatar of himself destroying the town. Yamada (Gumpy) always wanted to make Kaiju movies, but now approaching middle age he’s given up most of his dreams and aspirations and lives a dull life working in the tourism division of the local council. An opportunity presents itself when he’s put in charge of a PR video for the town at the behest of its ultra-conservative mayor.

Junichiro Yagi’s Kaiju Guy! (怪獣ヤロウ!Kaiju Yaro!) has a meta quality given that it’s about a film designed to promote the local area, but there are many other parallels in play. The first would be Yamada’s unsatisfying life standing in for that of a corporate drone, while the mayor (Michiko Shimizu) is later cast as the villain precisely because of her reverence for “tradition” and is under the impression that changing anything would be a betrayal of her ancestors in a nod to the rigidity of local government. Yamada’s teacher had told him to smash through the constraints, though that’s something he’s only just beginning to find the strength to do.

Though Yamada immediately suggests making a kaiju movie, he’s quickly shot down and reminded the mayor wants a conventional puff piece they can use to promote the town. Back in middle school, everyone had laughed at him for his DIY kaiju movie except his teacher who told him not to worry about what other people think and that those who challenge the status quo will always come in for attack or ridicule. Back then, the town of Seki had been the monster, though this time it’s supposed to be the victim that will eventually be saved. The mayor’s script had ironically been for a particular brand of hometown movie that’s become common in Japanese cinema in recent years in which a young person has their dreams crushed in Tokyo and rediscovers the charms of the place where they grew up after returning home in defeat. But there is something quite sad about the juxtaposition of Yamada thinking through the themes of the movie while riding his moped along empty streets which are flanked by rows closed shops.

The economic possibilities of the town becoming a tourist hotspot if the movie does its job might be one reason why many of the local businesses immediately pitch in to help besides a desire to display their hometown pride. Of course, most of them pull out when Yamada reimagines it as a kaiju movie even if he has a few supporters who think a kaiju movie might be fun and interesting way to sell the positives of Seki. In the course of making his movie, with the help of a grumpy, retired kaiju movie master by the name of Honda (Akaji Maro), Yamada discovers a way to use various local assets, such as filming sparks at the factory to create the fire-breathing effect and capturing the strange sound of a local bird for its roar. The heroes of the film become the local businesses supporting it who appear as a mini squad teaming up to fight the monster, while Yamada himself plays the marauding beast and “saviour” of the town going after the mayor and city hall to challenge their conservative insistence on tradition.

What he eventually discovers is that even the mayor herself is oppressed by “tradition supremacy” and once had to give up her own hopes and dreams to conform to her family’s insistence on the way things should be done. Her abrupt decision to make the film may have been a reflection of her latent desire for change, both for herself and for Seki even as she constantly harps on about cormorant fishing and sword making which are apparently the two biggest draws. Ironically, the film completely fulfils its role as a PR movie for Seki capturing the small-town charms of the area along with its warm community spirit. Smashing through barriers with his kaiju movie, Yamada’s dull and grey existence is suddenly brightened through accessing his creativity and having his artistic desires validated by those around him. Not only are kaiju movies not naff or nerdy, but a source of fun that can bring the community together as well encourage visitors from outside if only to explore the kind of place that could have produced something so wonderfully unconventional.

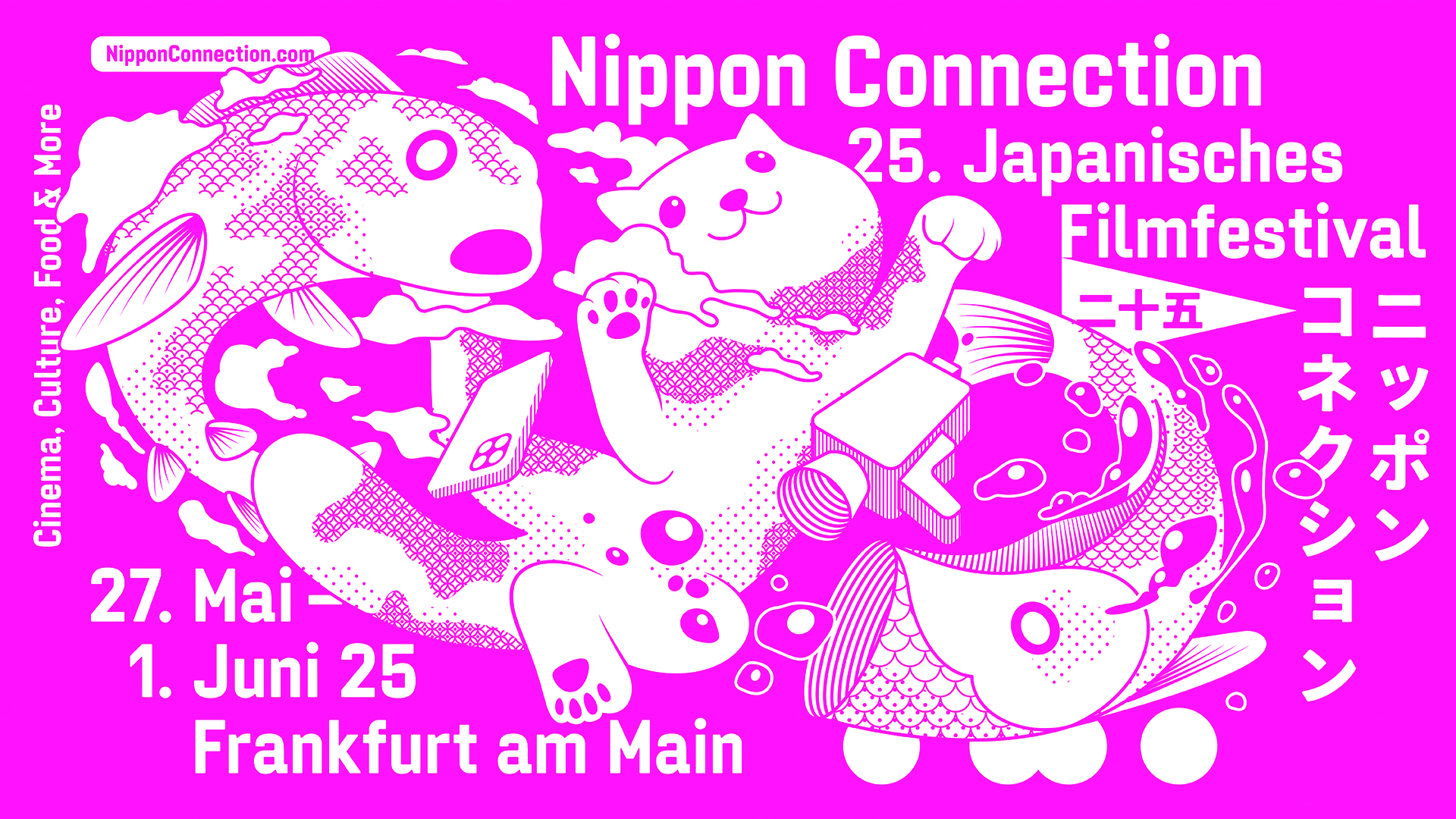

Kaiju Guy! screens 30th May as part of this year’s Nippon Connection.

Trailer (English subtitles)

Images: © 2024 Team KAIJU GUY!