Three sisters embark on an ill-advised family trip to a rundown onsen to celebrate their difficult to please mother’s birthday but eventually discover a kind of serenity in their sisterhood in Ryosuke Hashiguchi’s To Mom, with Love (お母さんが一緒, Okasan ga Issho). Best known for his queer-themed films, this is Hashiguchi’s first feature in a decade and was made to celebrate the 25th anniversary of Shochiku’s family drama channel. As such it explores the perspectives of each of the sisters along with contemplating that of their unseen mother as they each find themselves trapped within oppressively patriarchal social structures.

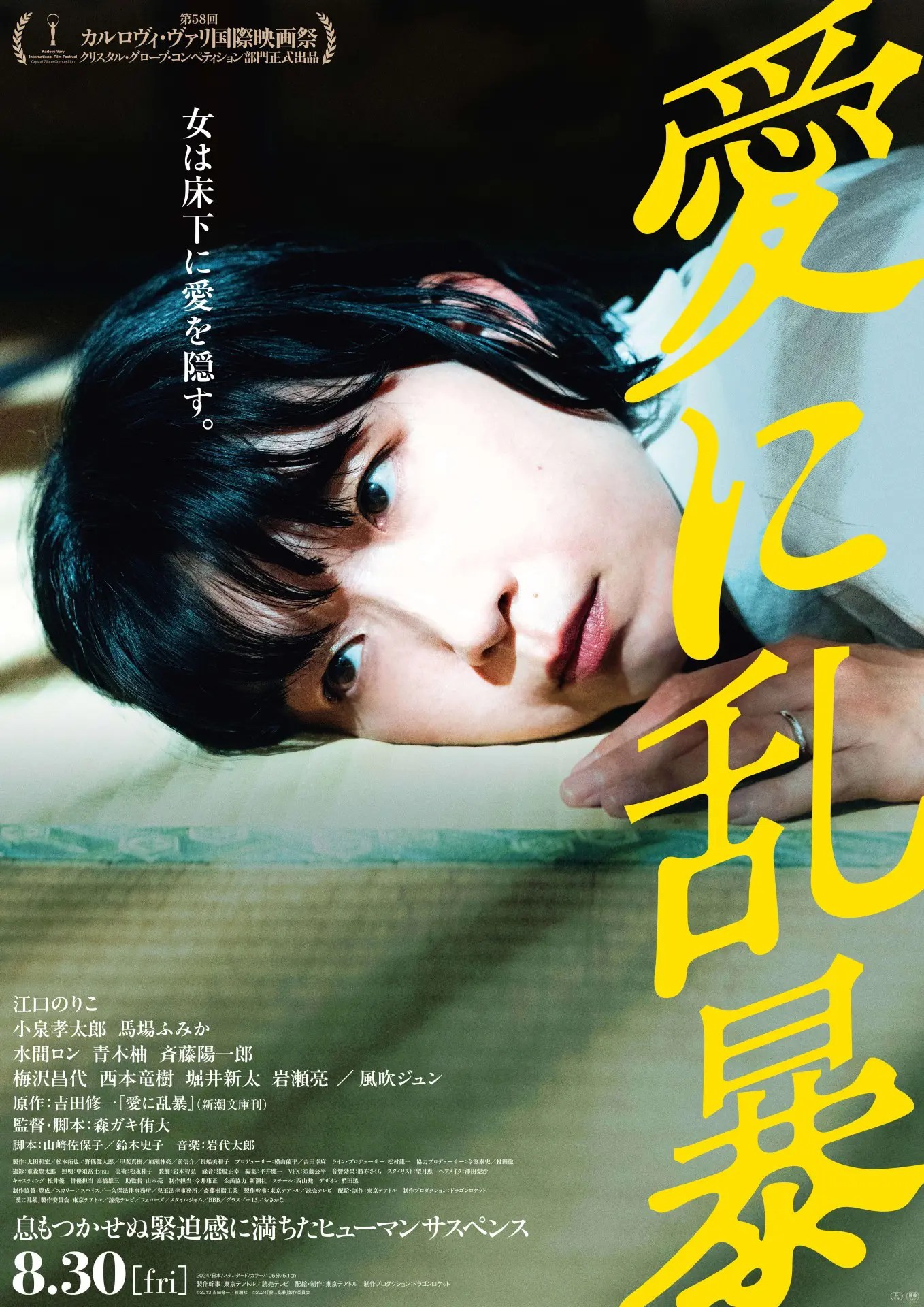

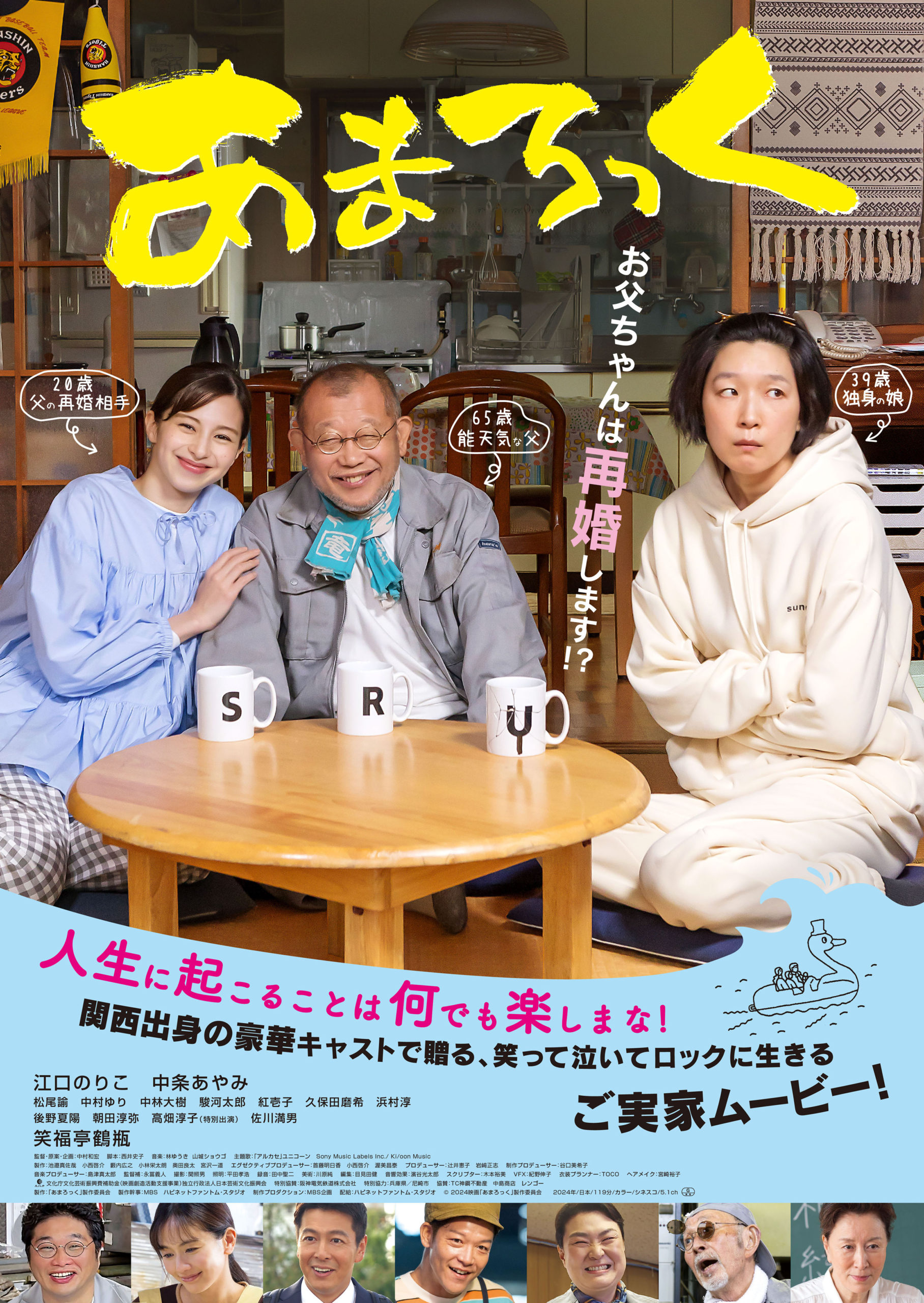

Which is to say, the main problem is marriage. All the mother wants for her birthday is a grandchild but none of the sisters is married and the older two are ageing out of the prospect of motherhood. 40-ish Yayoi (Noriko Eguchi) has like her mother become somewhat embittered, constantly carping on about the facilities at the old-fashioned inn which she says smells of mould rather than the refreshing scent of tatami mats. She snipes at her sister Manami (Chika Udisa), 35, who has had a string of unsuccessful relationships including one with a married man, while the youngest sister, Kiyomi (Kotone Furukawa), 29, is about to spring the surprise that she is engaged to the son of their local liquor store, Takahiro (Fallgachi Aoyama), as a sort of birthday present for her nagging mother.

This pressure to marry and have children is overwhelming and largely stemming from the mother herself, but it’s clear that she suffered in life because of an arranged marriage to the sisters’ father which was ultimately unhappy. Manami recalls a rare family holiday in which her parents argued in a restaurant and her father violently threw his fork to the floor. He wasn’t an easy person either, but the mother still wants nothing more than to inflict this same misery on her daughters as means of declaring her own life successful. Manami may have a point when she says that they shouldn’t have come on this trip given that it doesn’t seem like something their mother would enjoy and in fact like Yayoi what she apparently enjoys most is complaining about it before going to bed early and ruining everyone’s plans for the evening.

While all this is going on, Kiyomi has Takehiro hiding out in their room waiting for the signal to join them and doing so patiently without complaint. Though he seems fairly clueless, in contrast to the sisters he’s a calm, easy-going presence and eager to keep the peace. He might be a bit of a flirt, not exactly objecting to Manami’s inappropriately flirty behaviour and hanging out with two other women in the inn’s lounge while Kiyomi bickers with her sisters, but otherwise seems like he just might be nice. An only child, he might secretly be a little jealous of Kiyomi for having siblings to bicker with, though that’s something that Kiyomi is too insensitive to notice at least right away. In any case, his family life seems to have been much warmer and down to earth than that of the sisters who though they berate each other for blaming their problems on others struggle to let go of their familial traumas.

In part, that’s why Takahiro’s arrival sparks such a crisis for it means that Kiyomi will be moving on to the conventionally domestic future which has eluded Yayoi and Manami though they each appear to have desired it. Kiyomi says she was left with no choice but to spring this surprise because her mother wouldn’t listen to her otherwise, but it perhaps also hints at her self-doubt that she will really be able to fulfil these roles as wife and mother or that her own marriage will be any happier than her parents’. Tempers rise and grievances are aired, but in the end you can only really have these incredibly raw arguments with family because they’re the only ones who’ll forgive you once the storm has cleared. Though it may have been a bad idea to come on this trip, there is something in the healing powers of the waters or “power spots” at the local shrine which even seems to cause their constantly “negative” mother to say something nice even as the sisters realise that in the end they only have each other but perhaps need little else.

To Mom, With Love screens as part of this year’s Japan Foundation Touring Film Programme.

Trailer (Japanese subtitles)

Images: ©2024 SHOCHIKU BROADCASTING Co., Ltd.