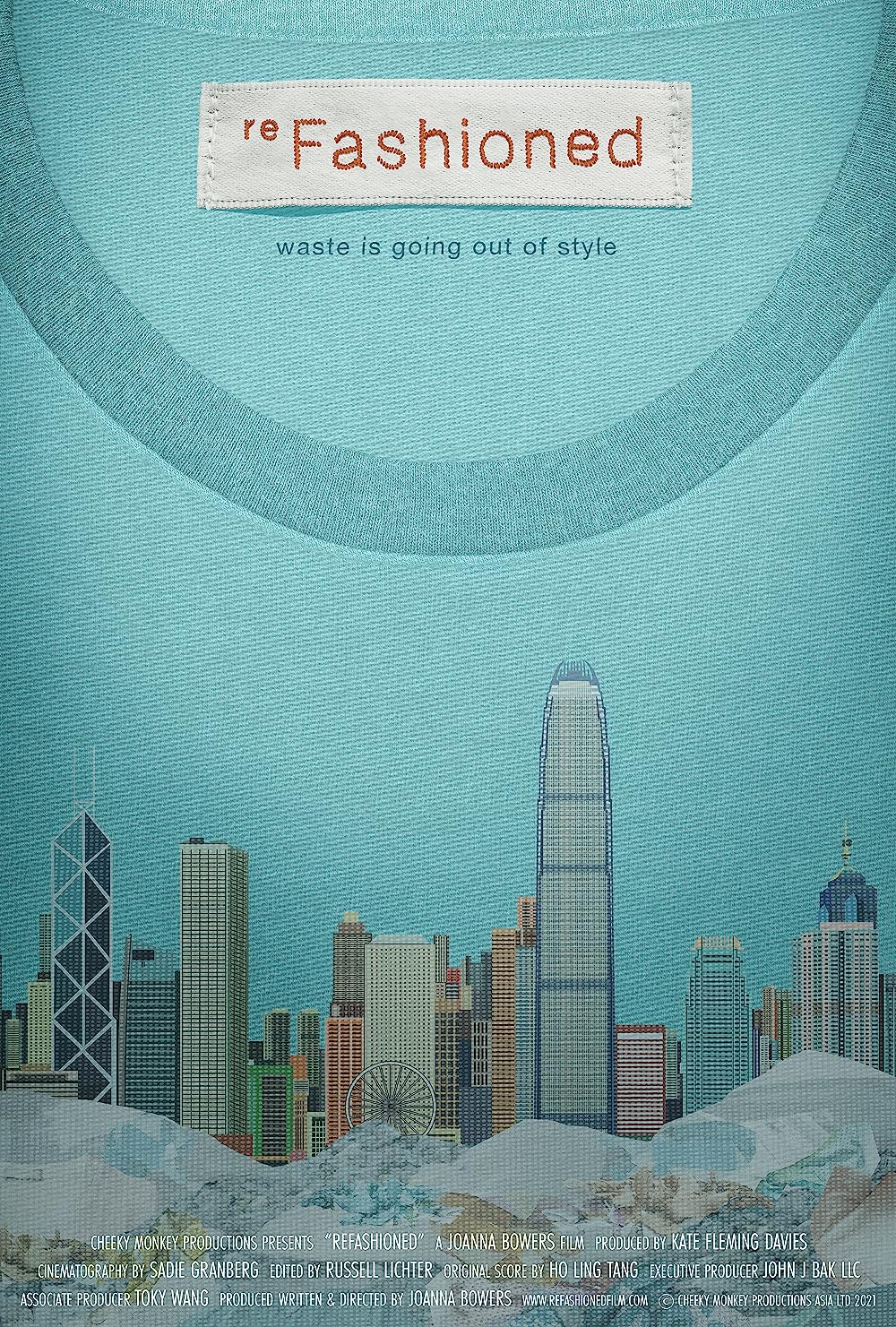

At the beginning of the consumerist era, our mentalities began to shift away from durability to disposability and we only desired that which we could throw away. But every time we throw something we don’t need anymore over our shoulder, the pile of discarded items grows higher and is already beginning to overshadow us. Joanna Bowers’ documentary ReFashioned examines the environmental impact of fast fashion and follows a series of Hong Kongers working towards initiatives to encourage recycling or reuse of textiles and plastic.

The change in our mindset is most clearly reflected in the startup created by an American expat to sell secondhand children’s outfits in which the concept of pre-owned clothing is itself sold as something “new”. As she points out, in Chinese culture there has long been a resistance to the idea of buying secondhand born of the fear of inheriting the bad luck of the previous owner though there seems to be less class-based stigma as might be found in the West where there has often been a sense of shame connected to dressing one’s children in handmedowns. Similarly, where parents might once have given away clothing their children had outgrown to friends and relatives they may now be less likely to do so if think they still have monetary value. Donations to charity shops and thrift stores may suffer the same fate ironically depriving those who cannot afford to buy brand new of the opportunity to buy at all.

Meanwhile, another interviewee remarks that the battle still lies in the mind of the consumer who remains unconvinced by the idea of recycling when they know that most of what they recycle ends up in landfill anyway. A government-backed initiative aims for a new approach in the recycling of textiles in which a robotised production line can sort by colour, respin thread, and produce new knitted garments while other less versatile fibres can be repurposed for carpets and upholstery. They have an end goal of creating a system in which the consumer would be able to bring their old clothes and have them deconstructed and remade by the machine into new designs allowing them to upcycle items they believed had simply gone out of style. Then again, the fashion show they put on to showcase their achievements is geared less towards the everyday than the catwalk which is admittedly designed to prove to brands that recycled material is just as good as brand new but perhaps also leans in to a fast fashion mentality if only more sustainably rather than returning to an age of well made garments designed for longterm use.

It should also be noted that the documentary received funding from high street clothing store H&M whose efforts towards sustainability are given prominent mention which also suggests that sustainability must be made compatible with the consumerist mindset rather than undercutting it. The problem is largely of economics in that it simply does not make sense to recycle when the costs outweigh the benefits to the average business. Another young man has started a company planning to recycle plastic bottles and himself admits that his end goal would also be to reduce their usage in the first place and make himself irrelevant but in any case is told by prospective investors that the business has little viability because of its logistical costs and small scale. This would seem to be the barrier to the creation of the “circular economy” proposed by some of the other interviewees.

The earlier part of the documentary had reflected on the changing economic fortunes of Hong Kong in which textile magnates from Shanghai had set up factories in the city but once the Mainland began to open itself up in the 1980s moved there to take advantage of significantly reduced labour costs leaving many local people unemployed. There is then something quite remarkable in the decision to redevelop a former textile mill as an ultramodern recycling centre, the first of its kind in Hong Kong and perhaps the world, avoiding the additional energy costs of deconstruction and reconstruction while saving the unique architecture of a mid-20th century industrial building. This is perhaps the ultimate example of “refashioning” demonstrating how the old can be adapted for use by the new, even if sustainable solutions for our increasingly consumerist lifestyles still feel very far away.

ReFashioned Dream Home streamed as part of this year’s Odyssey: A Chinese Cinema Season.

Original trailer (English dialogue)