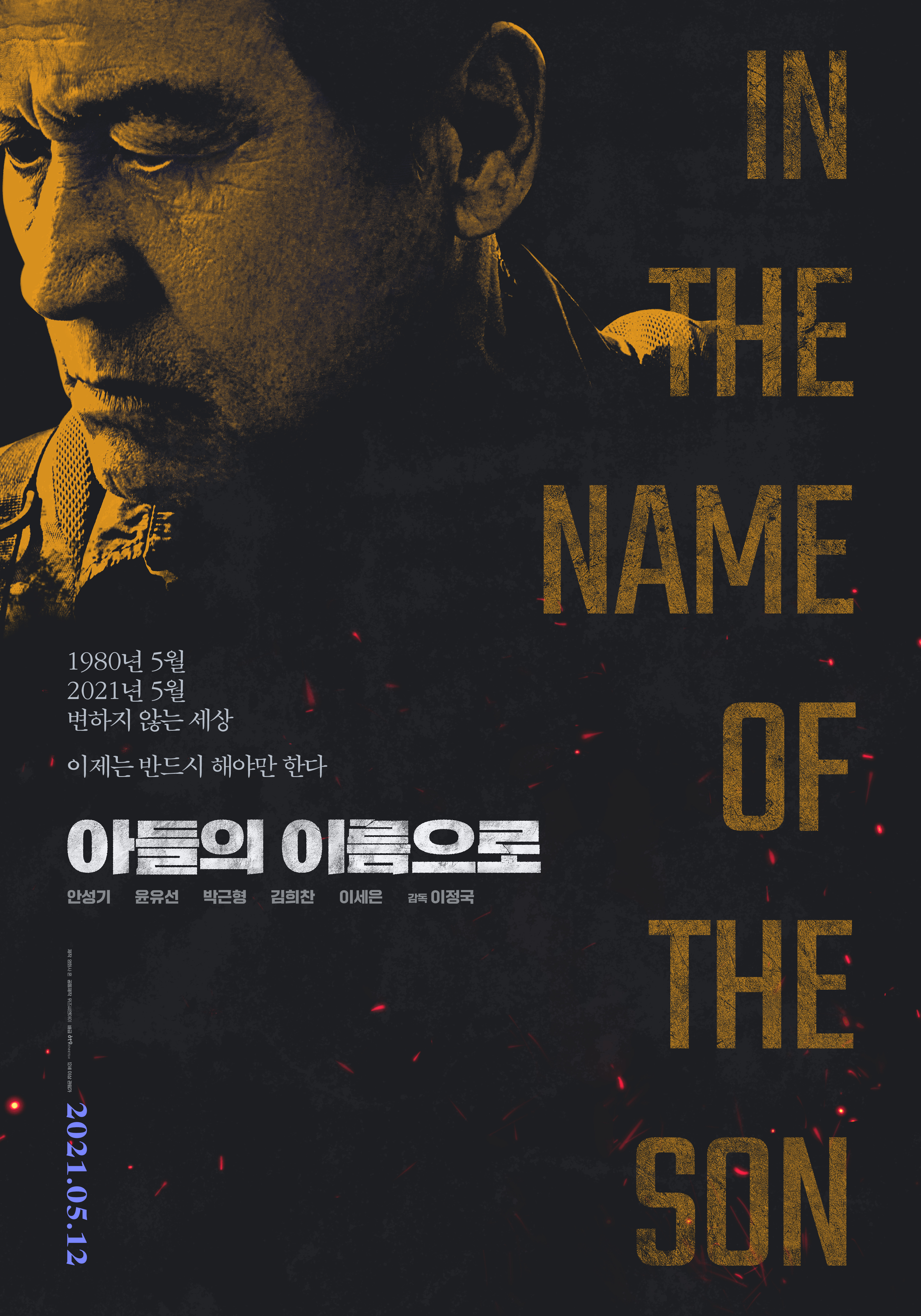

An elderly man suffering with a brain tumour and advanced dementia is determined to expose the abuses of the colonial past all too easily forgotten by the contemporary society in Lee Il-hyung’s remake of the 2015 Atom Egoyan film of the same name, Remember (리멤버). The film’s title works on multiple levels, firstly in the mind of the hero who both wants to remember and doesn’t as he feels his mind slipping away, and then in the minds of the men he seeks asking them both to remember the man who’s come calling with vengeance on his mind and who it is they really are.

As in many other similarly themed films of recent times, Pli-ju’s (Lee Sung-min) main problem is that those who chose to collaborate with the Japanese during the colonial era and directly contributed to the deaths of all his family members have largely gone on to extremely successful careers at the heart of the establishment. Ironically enough, right-wing Korean nationalist ideology is largely pro-Japan and the legacy of Japanese militarism was a key component in the post-war military dictatorships of Park Chung-hee and Chun Doo-Hwan. To that extent, Pil-ju is the inspector that calls visiting each of the men who caused the deaths of his father, brother, and sister in turn while exposing a series of colonial abuses. One of the men he visits is a working professor who teaches that Japanese colonial rule was actually beneficial in that it helped “modernise” the society though building infrastructure such as roads and railways without really considering that they were largely built with forced labour.

This casual disregard for human life has continued into the present day with the general Pil-ju targets, Chi-deok (Park Geun-hyung), also the head of the company, in which the Japanese effectively have a controlling share, responsible for a workplace accident that injured the father of Pil-ju’s getaway driver In-gyu (Nam Joo-hyuk) and refused to compensate him. Chi-deok, a hero of the Korean War, even makes a rousing speech instructing the audience that they must remember those who fell in defence of democracy which is a little rich seeing as his values are anything but democratic. Chi-deok also tries to justify himself to the police officer investigating the murder of the first man Pil-ju knocked off that those days were just about survival and that “Korea” no longer existed so all he could do to save it was to become Japanese. But like many of the other men, such as the professor who tricked Pil-ju’s brother into forced labour in a mine where he eventually died, he did so for personal advancement wilfully selling out his fellow countrymen throwing those who refused to change their names or continued to speak Korean in jail while sending off their sisters to become comfort women for the Japanese army.

The first man that Pil-ju killed tortured his father to death on a trumped up charge so he could steal his land. It’s not even ideology, it’s just greed and oppression. Everyone keeps telling him that no one cares about this kind of thing anymore, but conservative politicians nevertheless continue to weaponise it suggesting that anything is permissible in the battle against communism while imperialism is therefore a lesser evil. Pil-ju’s dementia is a metaphor for the literal erasure of history and the simple act of forgetting, the process by which many of these men have been able to rewrite their pasts to justify their actions. Yet it’s also true that there are things Pil-ju too does not want to remember and actively denies until finally forced to reckon with himself, with his complicity, guilt, and regret that he was as Chi-deok puts it not all that different as a man who survived those times when so many did not. Shot through with a gentle humour, Lee’s admittedly unsubtle drama (a Japanese soldier named Tojo literally says he’s going end the pacifist constitution so Japan can start wars whenever it feels like it) is also a gentle tale of intergenerational bonding as Pil-ju comes to develop a paternal affection for his workplace buddy In-gyu that suggests the past is only exorcised when spoken and passed down to new generations free of justifications or omissions and most importantly remembered as it was by those who really lived it.

Original trailer (no subtitles)

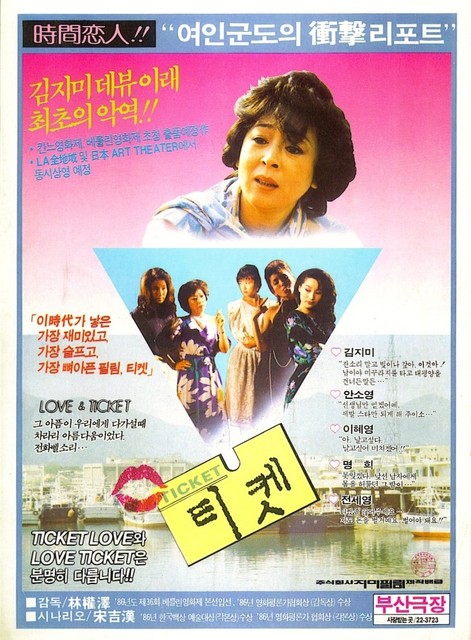

Review of Jo Sung-hee’s The Phantom Detective (탐정 홍길동: 사라진 마을, Tamjung Honggildong: Sarajin Maeul) first published by

Review of Jo Sung-hee’s The Phantom Detective (탐정 홍길동: 사라진 마을, Tamjung Honggildong: Sarajin Maeul) first published by