Yasujiro Shimazu may not be as well known as some of his contemporaries such as the similarly named Yasujiro Ozu and Hiroshi Shimizu, but during in his brief yet prolific career which was cut short by his early death just before the end of the war, Shimazu became the father of one of the most prominent genres in Japanese cinema – the “shomingeki”, which focussed on the lives ordinary lower middle-class people. Shimazu’s early films were noted for their unusual naturalism but 1937’s The Trio’s Engagements (婚約三羽烏, Konyaku Sanbagarasu) is pure Hollywood in its screwball tale of three silly young men and their respective romantic difficulties which are sorted out with the amusing kind of neatness you can only find in a 1930s cinematic farce.

Yasujiro Shimazu may not be as well known as some of his contemporaries such as the similarly named Yasujiro Ozu and Hiroshi Shimizu, but during in his brief yet prolific career which was cut short by his early death just before the end of the war, Shimazu became the father of one of the most prominent genres in Japanese cinema – the “shomingeki”, which focussed on the lives ordinary lower middle-class people. Shimazu’s early films were noted for their unusual naturalism but 1937’s The Trio’s Engagements (婚約三羽烏, Konyaku Sanbagarasu) is pure Hollywood in its screwball tale of three silly young men and their respective romantic difficulties which are sorted out with the amusing kind of neatness you can only find in a 1930s cinematic farce.

Shuji Kamura (Shuji Sano) has been looking for a job in Japan’s depression hit Tokyo for some time and his long suffering girlfriend, Junko (Kuniko Miyake), has finally gotten fed up with his listlessness and decided it might be better if she left him on his own for a while to sort himself out. Slightly panicked, Shuji heads off to see about a job at a department store specialising in rayon fabrics. Undergoing a rather odd interview, he meets two other men in the same position – well to do Ken Taniyama (Ken Uehara), and down on his luck chancer Shin Miki (Shin Saburi). Luckily all three are employed that day and start working in the store but trouble brews when they each fall for the charms of the boss’ daughter, Reiko (Mieko Takamine).

Despite the contemporary setting and the difficulty of finding work for even educated young men providing a starting point for the drama, Shimazu creates a truly “modern” world full of neon lights and Westernised fashions. The trio work in a department store which sells rayon – a cheap substitute for silk being sold as the latest sophisticated import from overseas, and the store itself is designed in a modernist, art deco style which wouldn’t look out of place in any Hollywood film of the same period. Likewise, though the store is largely staffed by men catering to a largely female clientele, it maintains a sophisticated atmosphere with staff members expected to provide solicitous care and attention to each and every customer.

The guys do this with varying degrees of commitment as Shin and Ken pull faces at each other across the floor and Shuji wastes time on the roof. Shimazu packs in as many quick fire gags as possible beginning the the bizarre job interviews in which Shuji ends up doing some very in-depth role play while Shin expounds on the virtues of rayon as if he were some kind of fabrics genius. Shin Miki is your typical chancer, turning up to his job interview with a thick beard which he later shaves making him all but unrecognisable, and even cheating Ken out of a few coins he’s been using to show off his magic tricks before bamboozling his way into Shuji’s flat.

The central, slapstick conceit is that each of the guys is about to jettison their previous partners for a false infatuation with the beautiful Reiko. Shuji is mostly on the rebound from Junko who may or may not come back to see if he’s sorted himself out, while Ken is uncertain about an arranged marriage, and Shin has a secret country bumpkin girlfriend he doesn’t want anyone to know about. Their respective crushes nearly spell the end for their friendship but then Reiko has her own ideas about marriage which don’t involve shop boys or a future in the rayon business. Eventually the guys realise they’ve all been a little silly and run back into the arms of the women they almost threw over, finding happiness at last in their otherwise ordinary choices.

Shimazu makes brief use of location shoots as Shin and Reiko walk along the harbour but mostly sticks to stage sets including the noticeably fake cityscape backdrop on the shop’s roof. The major draw is the “trio” at the centre which includes some of Shochiku’s most promising young leading men who would all go on to become huge stars including 30s matinee idol Ken Uehara, Shuji Sano, and Shin Saburi. Light and filled with silly, studenty humour The Trio’s Engagements is a deliberately fluffy piece designed to blow the blues away in increasingly difficult times, but even if somewhat lacking in substance it does provide a window onto an idealised 1930s world of Westernised flappers, cheap synthetic products, and frivolous romance.

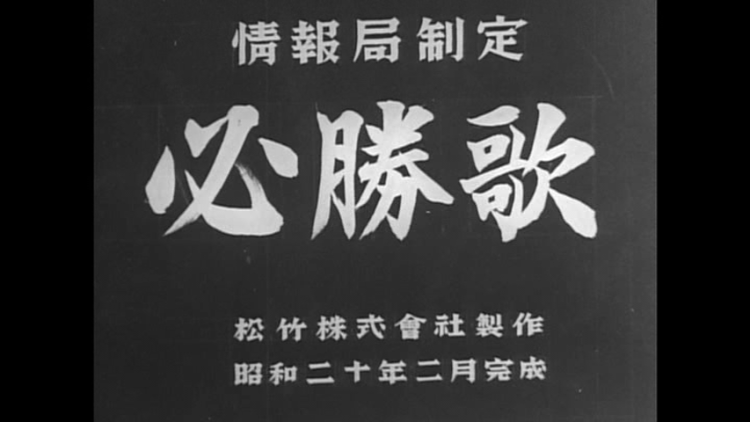

Completed in 1945, Victory Song (必勝歌, Hisshoka) is a strangely optimistic title for this full on propaganda effort intended to show how ordinary people were still working hard for the Emperor and refusing to read the writing on the wall. Like all propaganda films it is supposed to reinforce the views of the ruling regime, encourage conformity, and raise morale yet there are also tiny background hints of ongoing suffering which must be endured. Composed of 13 parts, Victory Song pictures the lives of ordinary people from all walks of life though all, of course, in some way connected with the military or the war effort more generally. Seven directors worked on the film – Masahiro Makino, Kenji Mizoguchi, Hiroshi Shimizu, Tomotaka Tasaka, Tatsuo Osone, Koichi Takagi, and Tetsuo Ichikawa, and it appears to have been a speedy production, made for little money though starring some of the studio’s biggest stars in smallish roles.

Completed in 1945, Victory Song (必勝歌, Hisshoka) is a strangely optimistic title for this full on propaganda effort intended to show how ordinary people were still working hard for the Emperor and refusing to read the writing on the wall. Like all propaganda films it is supposed to reinforce the views of the ruling regime, encourage conformity, and raise morale yet there are also tiny background hints of ongoing suffering which must be endured. Composed of 13 parts, Victory Song pictures the lives of ordinary people from all walks of life though all, of course, in some way connected with the military or the war effort more generally. Seven directors worked on the film – Masahiro Makino, Kenji Mizoguchi, Hiroshi Shimizu, Tomotaka Tasaka, Tatsuo Osone, Koichi Takagi, and Tetsuo Ichikawa, and it appears to have been a speedy production, made for little money though starring some of the studio’s biggest stars in smallish roles. Japan’s political climate had become difficult by 1938 with militarism in full swing. Young men were disappearing from their villages and being shipped off to war, and growing economic strife also saw young women sold into prostitution by their families. Cinema needed to be escapist and aspirational but it also needed to reflect the values of the ruling regime. Adapted from a novel by Katsutaro Kawaguchi, Aizen Katsura (愛染かつら) is an attempt to marry both of these aims whilst staying within the realm of the traditional romantic melodrama. The values are modern and even progressive, to a point, but most importantly they imply that there is always room for hope and that happy endings are always possible.

Japan’s political climate had become difficult by 1938 with militarism in full swing. Young men were disappearing from their villages and being shipped off to war, and growing economic strife also saw young women sold into prostitution by their families. Cinema needed to be escapist and aspirational but it also needed to reflect the values of the ruling regime. Adapted from a novel by Katsutaro Kawaguchi, Aizen Katsura (愛染かつら) is an attempt to marry both of these aims whilst staying within the realm of the traditional romantic melodrama. The values are modern and even progressive, to a point, but most importantly they imply that there is always room for hope and that happy endings are always possible. Isn’t it sad that it’s always the kids that end up hurt when parents fight? Throughout Shimizu’s long career of child centric cinema, the one recurring motif is in the sheer pain of a child who suddenly finds the other kids won’t play with him anymore even though he doesn’t think he’s done anything wrong. Four Seasons of Children (子どもの四季, Kodomo no Shiki) is actually a kind of companion piece to

Isn’t it sad that it’s always the kids that end up hurt when parents fight? Throughout Shimizu’s long career of child centric cinema, the one recurring motif is in the sheer pain of a child who suddenly finds the other kids won’t play with him anymore even though he doesn’t think he’s done anything wrong. Four Seasons of Children (子どもの四季, Kodomo no Shiki) is actually a kind of companion piece to  It would be a mistake to say that Hiroshi Shimizu made “children’s films” in that his work is not particularly intended for younger audiences though it often takes their point of view. This is certainly true of one of his most well known pieces, Children in the Wind (風の中の子供, Kaze no Naka no Kodomo), which is told entirely from the perspective of the two young boys who suddenly find themselves thrown into an entirely different world when their father is framed for embezzlement and arrested. Encompassing Shimizu’s constant themes of injustice, compassion and resilience, Children in the Wind is one of his kindest films, if perhaps one of his lightest.

It would be a mistake to say that Hiroshi Shimizu made “children’s films” in that his work is not particularly intended for younger audiences though it often takes their point of view. This is certainly true of one of his most well known pieces, Children in the Wind (風の中の子供, Kaze no Naka no Kodomo), which is told entirely from the perspective of the two young boys who suddenly find themselves thrown into an entirely different world when their father is framed for embezzlement and arrested. Encompassing Shimizu’s constant themes of injustice, compassion and resilience, Children in the Wind is one of his kindest films, if perhaps one of his lightest. Filmed in 1941, Notes of an Itinerant Performer (歌女おぼえ書, Utajo Oboegaki ) is among the least politicised of Shimizu’s output though its odd, domestic violence fuelled, finally romantic resolution points to a hardening of his otherwise progressive social ideals. Neatly avoiding contemporary issues by setting his tale in 1901 at the mid-point of the Meiji era as Japanese society was caught in a transitionary phase, Shimizu similarly casts his heroine adrift as she decides to make a break with the hand fate dealt her and try her luck in a more “civilised” world.

Filmed in 1941, Notes of an Itinerant Performer (歌女おぼえ書, Utajo Oboegaki ) is among the least politicised of Shimizu’s output though its odd, domestic violence fuelled, finally romantic resolution points to a hardening of his otherwise progressive social ideals. Neatly avoiding contemporary issues by setting his tale in 1901 at the mid-point of the Meiji era as Japanese society was caught in a transitionary phase, Shimizu similarly casts his heroine adrift as she decides to make a break with the hand fate dealt her and try her luck in a more “civilised” world. Naruse’s critical breakthrough came in 1933 with the intriguingly titled Apart From You (君と別れて, Kimi to Wakarete) which made it into the top ten list of the prestigious film magazine Kinema Junpo at the end of the year. The themes are undoubtedly familiar and would come dominate much of Naruse’s later output as he sets out to detail the lives of two ordinary geisha and their struggles with their often unpleasant line of work, society at large, and with their own families.

Naruse’s critical breakthrough came in 1933 with the intriguingly titled Apart From You (君と別れて, Kimi to Wakarete) which made it into the top ten list of the prestigious film magazine Kinema Junpo at the end of the year. The themes are undoubtedly familiar and would come dominate much of Naruse’s later output as he sets out to detail the lives of two ordinary geisha and their struggles with their often unpleasant line of work, society at large, and with their own families.