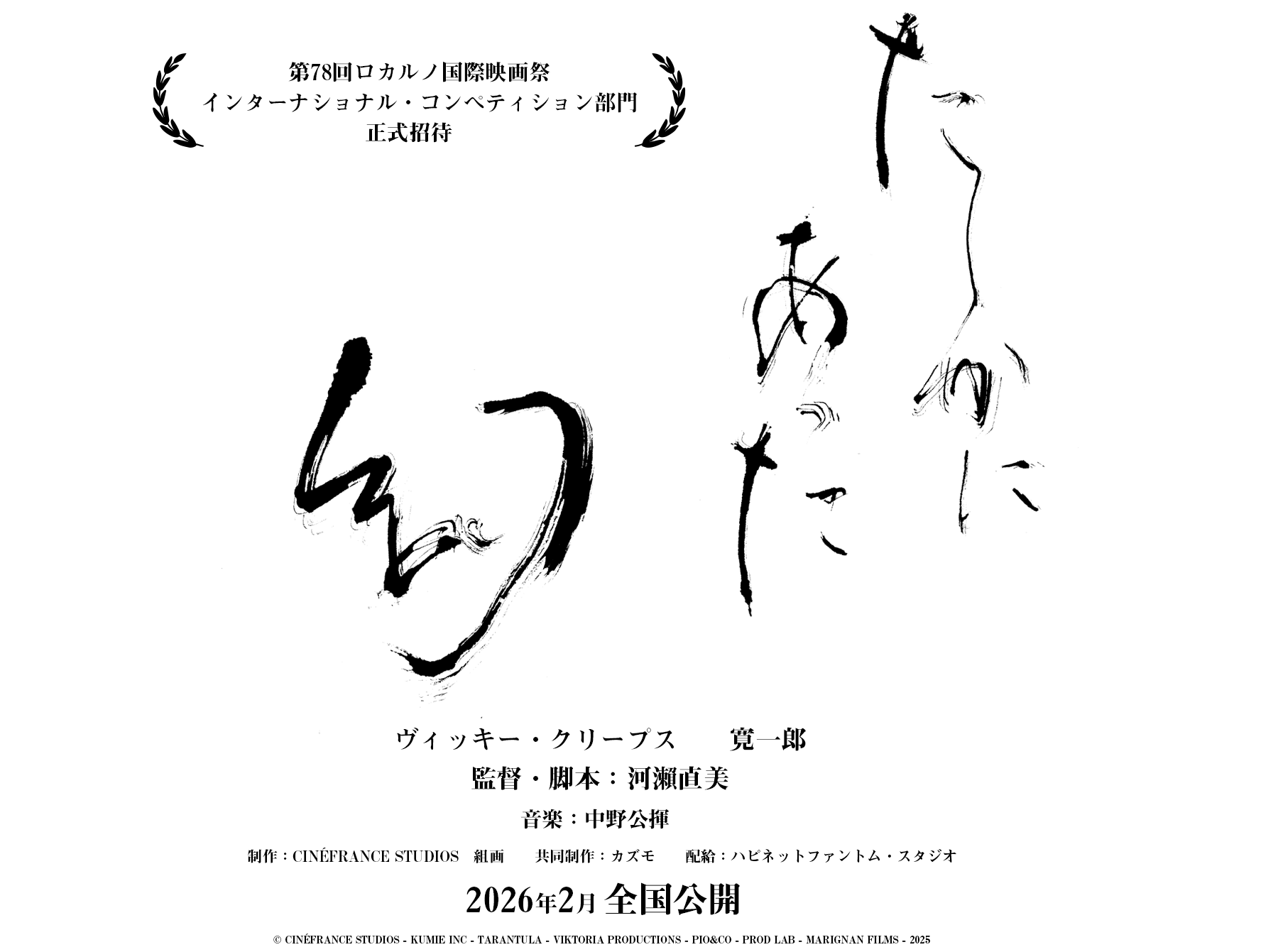

When is it that you can say someone is really dead? Grief-stricken paediatric organ transplant co-ordinator Corry (Vicky Krieps) finds herself pondering just this question while in Japan exploring differing attitudes to transplant surgery in Naomi Kawase’s latest, Yakushima’s Illusion (たしかにあった幻, Tashika ni Atta Maboroshi). Returning to her roots, Kawase includes several documentary-style sequences in which Japanese medical staff discuss traditional notions of life and death along with those relating to organ transplantation which remains taboo even in an otherwise advanced medical society.

One doctor relates that his own child had a transplant and they were plagued with harassment for “stealing” people’s organs. There’s a kind of ghoulishness in play, as if this practice were unholy in some way or were taking on a debt that can never be repaid. But from the perspective of the parents of children waiting for matches, there is indeed an undeniable sense of guilt involved given the knowledge that for their child to survive, another must have died and another parent just like them has suffered a loss. When a match finally comes up for one little boy, his mother feels conflicted knowing that a little girl that was ahead of them in the queue didn’t make it and now it’s like they’ve taken her slot. Meanwhile the parents of the child that died battle their grief and confusion but decide to allow his organs to be made made available so that he will in some sense at least on.

In this case, it was a heart transplant which presents the most complicated of existential questions given that traditionally death is marked by the cessation of the heart beating. Even when brain death has occurred, the body is considered to be living which obviously makes something like organ harvesting difficult if the patient is still considered to be “alive”. But on the other hand, it also means that death is infinitely postponed when the cessation of the heartbeat cannot be confirmed. Corry is haunted by the memory of an lover who disappeared without a trace and later discovers his family are trying to have him declared dead to smooth over an inheritance issue, though she objects because to her Jin is still alive even he’s not around.

It’s on Yakushima that Corry first meets Jin (Kanichiro), and one could say that he’s the illusion of the title. Indeed the Japanese title hints at his ethereal quality in translating as something like “the apparition that was really there”. He has an otherworldly quality and seems to exist outside of time with his old-fashioned camera and impish personality. Part of the film is set around Tanabata which is rooted in the tale of the Cowherd and the Weaver, Orihime and Hikiboshi, who were separated by a river and permitted to meet only on one day a year. This mythical quality adds to the sense that perhaps Jin was more ghost than man, a figment of Corry’s memory or a manifestation of her desires who was nevertheless himself consumed by loneliness. In a phenomenon known as “johatsu” in which people suddenly disappear without warning, Jin leaves her life as abruptly as he entered it leaving her with a series of regrets and lingering questions.

It’s this shifting sense of dislocation with which the film plays in moving, as Jin describes it, through the shifting moments of the heart exchanging linear time for emotional chronology. Having lost her mother in childbirth, Corry is consumed by a fear of abandonment and incurable loneliness that is compounded by the fact that people really do disappear from her life with alarming frequency which is perhaps why she is so invested in saving the lives of these young children. Bonding with a couple who lost their son to illness and now operate a bento stand supporting other parents, she searches for a way to let go without letting go which she perhaps finds in the serenity of nature now captured with sweeping drone shots such as that which takes us inside a tree in search of the self. Frequent cameos from former Kawase collaborators such as Machiko Ono and Masatoshi Nagase in small roles add to the elegiac feeling even if the final message seems to be that life goes on in the image of a still beating heart giving new life and new hope even in the midst of death and loss.

Yakushima’s Illusion screened as part of this year’s LEAFF.