A samurai’s soul in his sword, so they say. What is a samurai once he’s been reduced to selling the symbol of his status? According to Scabbard Samurai (さや侍, Sayazamurai) not much of anything at all, yet perhaps there’s another way of defining yourself in keeping with the established code even when robbed of your equipment. Hitoshi Matsumoto, one of Japan’s best known comedians, made a name for himself with the surreal comedies Big Man Japan and Symbol but takes a low-key turn in Scabbard Samurai, stepping back in time but also in comedic tastes as the hero tests his mettle as a showman in a high stakes game of life and death.

A samurai’s soul in his sword, so they say. What is a samurai once he’s been reduced to selling the symbol of his status? According to Scabbard Samurai (さや侍, Sayazamurai) not much of anything at all, yet perhaps there’s another way of defining yourself in keeping with the established code even when robbed of your equipment. Hitoshi Matsumoto, one of Japan’s best known comedians, made a name for himself with the surreal comedies Big Man Japan and Symbol but takes a low-key turn in Scabbard Samurai, stepping back in time but also in comedic tastes as the hero tests his mettle as a showman in a high stakes game of life and death.

Nomi Kanjuro (Takaaki Nomi) is a samurai on the run. Wandering with an empty scabbard hanging at his side, he pushes on into the wilderness with his nine year old daughter Tae (Sea Kumada) grumpily traipsing behind him. Eventually, Nomi is attacked by a series of assassins but rather than heroically fighting back as any other jidaigeki hero might, he runs off into the bushes screaming hysterically. Nomi and Tae are then captured by a local lord but rather than the usual punishment for escapee retainers, Nomi is given an opportunity to earn his freedom if only he can make the lord’s sad little boy smile again before the time is up.

Nomi is not exactly a natural comedian. He’s as sullen and passive as the little lord he’s supposed to entertain yet he does try to come up with the kind of ideas which might amuse bored children. Given one opportunity to impress every day for a period of thirty days, Nomi starts off with the regular dad stuff like sticking oranges on his eyes or dancing around with a face drawn on his chest but the melancholy child remains impassive. By turns, Nomi’s ideas become more complex as the guards (Itsuji Itao and Tokio Emoto) begin to take an interest and help him plan his next attempts. Before long Nomi is jumping naked through flaming barrels, being shot out of cannons, and performing as a human firework but all to no avail.

Meanwhile, Tae looks on with contempt as her useless father continues to embarrass them both on an increasingly large stage. Tae’s harsh words express her disappointment with in Nomi, berating him for running away, abandoning his sword and with it his samurai honour, and exposing him as a failure by the code in which she has been raised. She watches her father’s attempts at humour with exasperation, unsurprised that he’s failed once again. Later striking up a friendship with the guards Tae begins to get more involved, finally becoming an ally and ringmaster for her father’s newfound career as an artist.

Tae and the orphaned little boy share the same sorrow in having lost their mothers to illness and it’s her contribution that perhaps begins to reawaken his talent for joy. Nomi’s attempts at comedy largely fall flat but the nature of his battle turns out to be a different one than anyone expected. Tae eventually comes around to her father’s fecklessness thanks to his determination, realising that he’s been fighting on without a sword for all this time and if that’s not samurai spirit, what is? Nomi makes a decision to save his honour, sending a heartfelt letter to his little girl instructing her to live her life to the fullest, delivering a message he was unable to express in words but only in his deeds.

Matsumoto’s approach is less surreal here and his comedy more of a vaudeville than an absurd kind, cannons and mechanical horses notwithstanding. The story of a scabbard samurai is the story of an empty man whose soul followed his wife, leaving his vacant body to wander aimlessly looking for an exit. Intentionally flat comedy gives way to an oddly moving finale in which a man finds his redemption and his release in the most unexpected of ways but makes sure to pass that same liberation on to his daughter who has come to realise that her father embodies the true samurai spirit in his righteous perseverance. Laughter and tears, Scabbard Samurai states the case for the interdependence of joy and sorrow, yet even if it makes plain that kindness and understanding are worth more than superficial attempts at humour it also allows that comedy can be the bridge that spans a chasm of despair, even if accidentally.

Currently streaming on Mubi

Original trailer (no subtitles)

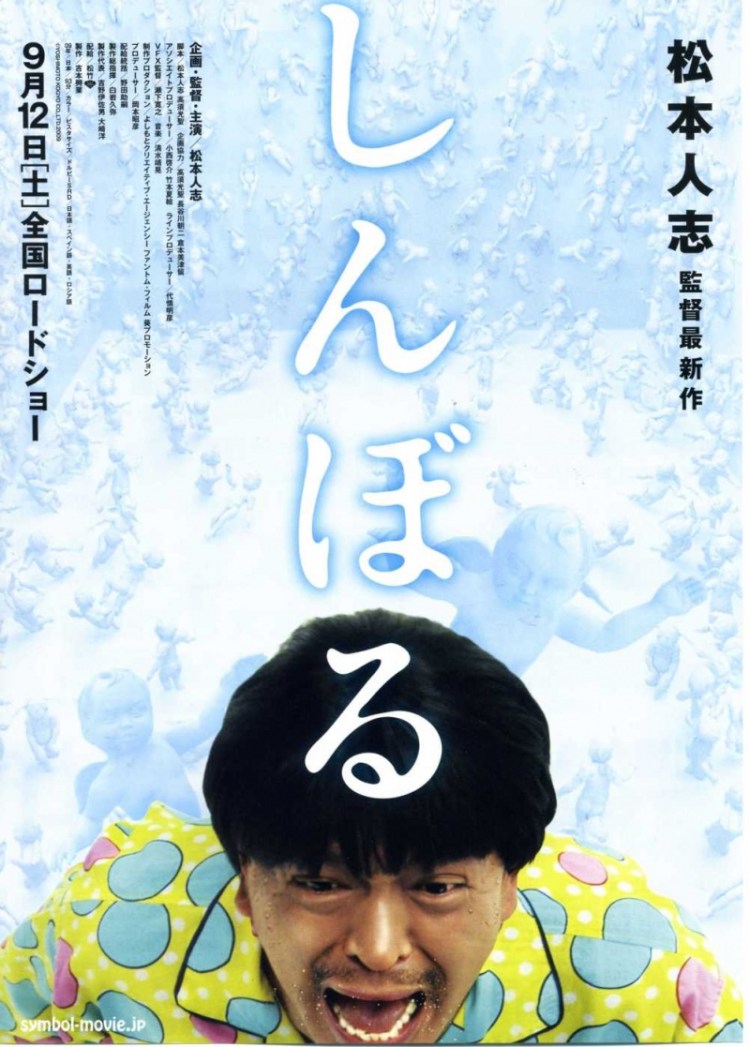

Symbol (しんぼる) – one thing which stands for another, sacrificing its own nature in service of something else. Hitoshi Matsumoto waxes philosophical in his follow up to Big Man Japan. Life, the universe, and everything converge in the seemingly unrelated tales of an unsuccessful Mexican luchador, and a confused Japanese man trapped in a surrealist nightmare. As expected, these two strands eventually meet, though not quite as one might expect.

Symbol (しんぼる) – one thing which stands for another, sacrificing its own nature in service of something else. Hitoshi Matsumoto waxes philosophical in his follow up to Big Man Japan. Life, the universe, and everything converge in the seemingly unrelated tales of an unsuccessful Mexican luchador, and a confused Japanese man trapped in a surrealist nightmare. As expected, these two strands eventually meet, though not quite as one might expect. Conventional wisdom states it’s better not to get involved with the yakuza. According to Hamon: Yakuza Boogie (破門 ふたりのヤクビョーガミ Hamon: Futari no Yakubyogami), the same goes for sleazy film execs who can prove surprisingly slippery when the occasion calls. Based on Hiroyuki Kurokawa’s Naoki Prize winning novel and directed by Shotaro Kobayashi who also adapted the same author’s Gold Rush into a successful WOWWOW TV Series, Hamon: Yakuza Boogie is a classic buddy movie in which a down at heels slacker forms an unlikely, grudging yet mutually dependent relationship with a low-level gangster.

Conventional wisdom states it’s better not to get involved with the yakuza. According to Hamon: Yakuza Boogie (破門 ふたりのヤクビョーガミ Hamon: Futari no Yakubyogami), the same goes for sleazy film execs who can prove surprisingly slippery when the occasion calls. Based on Hiroyuki Kurokawa’s Naoki Prize winning novel and directed by Shotaro Kobayashi who also adapted the same author’s Gold Rush into a successful WOWWOW TV Series, Hamon: Yakuza Boogie is a classic buddy movie in which a down at heels slacker forms an unlikely, grudging yet mutually dependent relationship with a low-level gangster. The world of shojo manga is a particular one. Aimed squarely at younger teenage girls, the genre focuses heavily on idealised, aspirational romance as the usually female protagonist finds innocent love with a charming if sometimes shy or diffident suitor. Then again, sometimes that all feels a little dull meaning there is always space to send the drama into strange or uncomfortable areas. Policeman and Me (PとJK, P to JK), adapted from the shojo manga by Maki Miyoshi is just one of these slightly problematic romances in which a high school girl ends up married to a 26 year old policeman who somehow thinks having an official certificate will make all of this seem less ill-advised than it perhaps is.

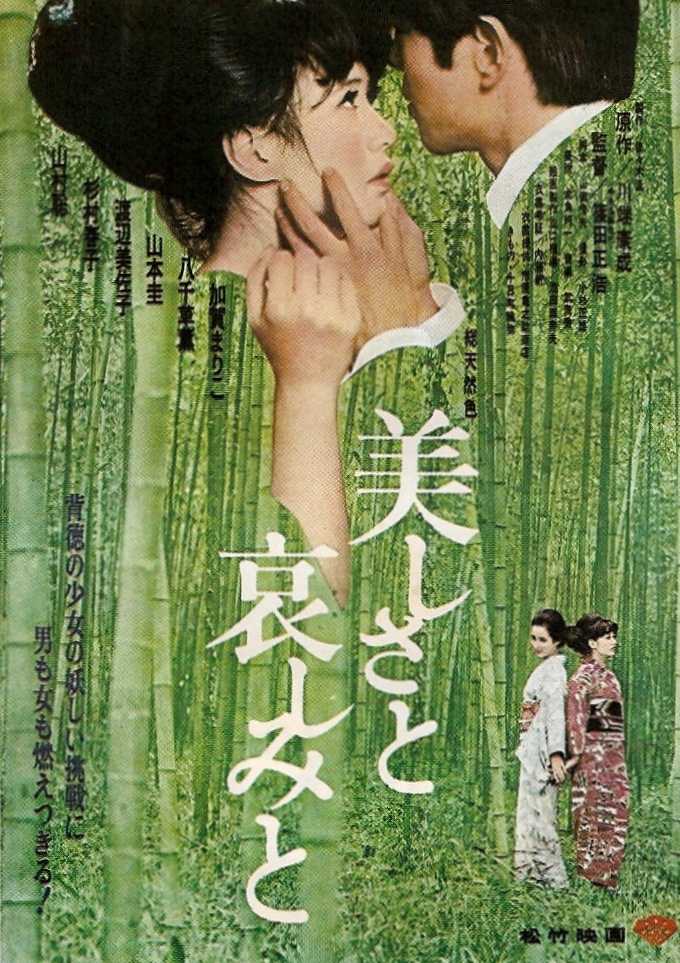

The world of shojo manga is a particular one. Aimed squarely at younger teenage girls, the genre focuses heavily on idealised, aspirational romance as the usually female protagonist finds innocent love with a charming if sometimes shy or diffident suitor. Then again, sometimes that all feels a little dull meaning there is always space to send the drama into strange or uncomfortable areas. Policeman and Me (PとJK, P to JK), adapted from the shojo manga by Maki Miyoshi is just one of these slightly problematic romances in which a high school girl ends up married to a 26 year old policeman who somehow thinks having an official certificate will make all of this seem less ill-advised than it perhaps is. Masahiro Shinoda, a consumate stylist, allies himself to Japan’s premier literary impressionist Yasunari Kawabata in an adaptation that the author felt among the best of his works. With Beauty and Sorrow (美しさと哀しみと, Utsukushisa to Kanashimi to), as its title perhaps implies, examines painful stories of love as they become ever more complicated and intertwined throughout the course of a life. The sins of the father are eventually visited on his son, but the interest here is less the fatalism of retribution as the author protagonist might frame it than the power of jealousy and its fiery determination to destroy all in a quest for self possession.

Masahiro Shinoda, a consumate stylist, allies himself to Japan’s premier literary impressionist Yasunari Kawabata in an adaptation that the author felt among the best of his works. With Beauty and Sorrow (美しさと哀しみと, Utsukushisa to Kanashimi to), as its title perhaps implies, examines painful stories of love as they become ever more complicated and intertwined throughout the course of a life. The sins of the father are eventually visited on his son, but the interest here is less the fatalism of retribution as the author protagonist might frame it than the power of jealousy and its fiery determination to destroy all in a quest for self possession. Masahiro Shinoda’s first film for Shochiku,

Masahiro Shinoda’s first film for Shochiku,  After such a long and successful career, Yoji Yamada has perhaps earned the right to a little retrospection. Offering a smattering of cinematic throwbacks in homages to both Yasujiro Ozu and Kon Ichikawa, Yamada then turned his attention to the years of militarism and warfare in the tales of a struggling mother,

After such a long and successful career, Yoji Yamada has perhaps earned the right to a little retrospection. Offering a smattering of cinematic throwbacks in homages to both Yasujiro Ozu and Kon Ichikawa, Yamada then turned his attention to the years of militarism and warfare in the tales of a struggling mother,  An Autumn Afternoon (秋刀魚の味, Sanma no Aji) was to be Ozu’s final work. This was however more by accident than design – despite serious illness Ozu intended to continue working and had even left a few notes relating to a follow up project which was destined never to be completed. Even if not exactly intended to become the final point of a thirty-five year career, An Autumn Afternoon is an apt place to end, neatly revisiting the director’s key concerns and starring some of his most frequent collaborators.

An Autumn Afternoon (秋刀魚の味, Sanma no Aji) was to be Ozu’s final work. This was however more by accident than design – despite serious illness Ozu intended to continue working and had even left a few notes relating to a follow up project which was destined never to be completed. Even if not exactly intended to become the final point of a thirty-five year career, An Autumn Afternoon is an apt place to end, neatly revisiting the director’s key concerns and starring some of his most frequent collaborators.

Children – not always the most tolerant bunch. For every kind and innocent film in which youngsters band together to overcome their differences and head off on a grand world saving mission, there are a fair few in which all of the other kids gang up on the one who doesn’t quite fit in. Given Japan’s generally conformist outlook, this phenomenon is all the more pronounced and you only have to look back to the filmography of famously child friendly director Hiroshi Shimizu to discover a dozen tales of broken hearted children suddenly finding that their friends just won’t play with them anymore. Where A Silent Voice (聲の形, Koe no Katachi) differs is in its gentle acceptance that the bully is also a victim, capable of redemption but requiring both external and internal forgiveness.

Children – not always the most tolerant bunch. For every kind and innocent film in which youngsters band together to overcome their differences and head off on a grand world saving mission, there are a fair few in which all of the other kids gang up on the one who doesn’t quite fit in. Given Japan’s generally conformist outlook, this phenomenon is all the more pronounced and you only have to look back to the filmography of famously child friendly director Hiroshi Shimizu to discover a dozen tales of broken hearted children suddenly finding that their friends just won’t play with them anymore. Where A Silent Voice (聲の形, Koe no Katachi) differs is in its gentle acceptance that the bully is also a victim, capable of redemption but requiring both external and internal forgiveness.

If there is a frequent criticism directed at the always bankable director Yoji Yamada, it’s that his approach is one which continues to value the past over the future. Recent years have seen him looking back, literally, in terms of both themes and style with remakes of films by two Japanese masters – Ozu in his Tokyo Story homage Tokyo Family, and Kon Ichikawa in Her Brother. While he chose to update both of those pieces for the modern day, 2008’s

If there is a frequent criticism directed at the always bankable director Yoji Yamada, it’s that his approach is one which continues to value the past over the future. Recent years have seen him looking back, literally, in terms of both themes and style with remakes of films by two Japanese masters – Ozu in his Tokyo Story homage Tokyo Family, and Kon Ichikawa in Her Brother. While he chose to update both of those pieces for the modern day, 2008’s