When the black ships appeared off the coast of Japan in 1853, it provoked a moment of crisis which eventually led to the fall of the Tokugawa Shogunate and the Meiji Restoration. Between those two events however lay a period of intense confusion as several groups and movements attempted to lay claim to the future direction of the nation. Many, such as the legendary figure Sakamoto Ryoma, held that above all else Japan needed to Westernise as quickly as possible in order to defend itself against foreign powers now far more technologically advanced than the Japan which had attempted to hold back time for over 200 years. Others felt quite the opposite, that what was needed was an end to the corrupt rule of the Shogunate and the restoration of power to the emperor while expelling foreign influence and going back into isolation.

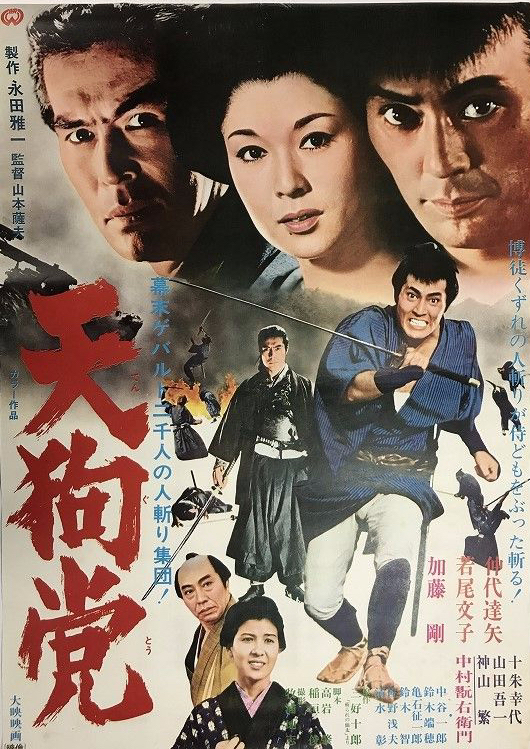

Satsuo Yamamoto’s Blood End (天狗党, Teng-to) dramatises this debate through the melancholy tale of the Mito Rebellion as a brutalised peasant farmer is sucked in by the idea of revolution but eventually betrayed by it in discovering that the samurai, even revolutionary samurai, will never change. They may claim they want an end to the feudal caste system and to live in a world where all men are equal, but continue to feel themselves entitled to more equality than others and insist on deference from those they still believe to be inferior.

The action begins with a scene familiar from many a jidaigeki in that a small farming community is being pressed to provide the usual amount of rice despite the failure of the harvest. Revolutionary yakuza Jingoza (Kanemon Nakamura) and egalitarian samurai Kada (Go Gato) stumble on the scene of a “stubborn” peasant being subjected to 100 blows as punishment for the village’s raising the unfairness of their situation with the local lord. Surviving his ordeal, Sentaro (Tatsuya Nakadai) asks only for water but is denied by his cruel samurai tormentor. Jingoza intervenes and offers him his flask along with some money by way of an apology on behalf of these savage nobles, a gesture for which Sentaro remains grateful. While many of his friends are exiled and lose their lands, Sentaro disappears from the village and becomes a yakuza himself, learning the art of the sword in preparation for his mission of revenge.

Meeting Jingoza by chance, he takes the opportunity to thank him and agrees to transport some money back to his family in a nearby village while he engages in urgent business in the mountains. While there, Sentaro ends up defending Jingoza’s steely daughter Tae (Yukiyo Toake) who is running something like an orphanage for children rendered fatherless by the ongoing chaos. It’s at Tae’s that he ends up running into Kada, who is a member of revolutionary movement “Tengu-to”, named for the mythical ogres with long noses and bright red faces. Sentaro ends up joining the movement, but gradually discovers that Tengo-to is not all he thought it to be. In the modern parlance, many of their actions are terrorist, they care little for human life and have no issue with looting wealthy houses as they prove after helping Sentaro assassinate the man who beat him, killing the man’s wife and servants and making off with his money as “military funds”. Sentaro is shocked, but only manages to get some of the money for himself to take back to Tae as a way of making amends. He continues to associate with Tengu-to despite his growing disillusionment with their philosophy.

The Mito clan were perhaps outliers in the great Bakumatsu culture war, running under the “Sonno Joi” banner but doing so alone and forcefully advocating that the emperor’s instruction to expel all foreigners with immediate effect be enforced. At least as far as Yamamoto’s revolutionaries go, they advocate for this not so much because they reject foreign influence but because they resent the country’s elites maintaining a stranglehold on the riches to be gained by foreign trade. Kada, however, claims to have a more revolutionary spirit in that he wants to improve conditions for farmers like Sentaro, protecting them from the “corrupt system” but he’s still a product of his society and finds the programming increasingly hard to break. Having recruited vast numbers of peasants to their cause and witnessing the failure of their campaign, the other leaders want to go to Kyoto to talk to the emperor but are embarrassed to go there in the company of so many men who are not samurai. The solution is that they simply kill them, because peasants aren’t really people anyway.

Sentaro thought they were “doing something good for peasants and the poor”, but samurai will always be “samurai” and eventually they will betray him. He wavers when Kada and the others ask him to assassinate Jingoza because he’s gone over to the Westernising cause, and is half talked round by his insistence that he’s acting blindly without thinking far enough ahead but himself finds it hard to break with the idea that samurai are honest and know what they’re doing.

Yamamoto is perhaps making a direct allusion to the imminent failure of the student movement in Japan which finds itself in much the same place as the Tengu-to, torn apart by infighting and increasingly corrupted by duplicitous dogma. Kada has a lot of fine ideas but he doesn’t act on them, doubling down on ruthlessness in complaining that Sentaro is too sentimental, insisting that emotion is the enemy. Sentaro, however, has figured out that the enemy is the sword and everything it represents. Jingoza’s “Restoration” is the one he should have been fighting for if he wanted to see a classless Japan, but the Tengu-to have misused his idealism for their own ends and turned him into a defender of his own oppression. Still, the Tengu-to are the ones who pay the price, their entreaties to the emperor falling on deaf ears with 353 retainers beheaded as punishment. Sentaro lives on, vowing he will never die, as he walks towards the “Restoration” of the future and away from the Blood End of an inherently corrupt insurrection.

Throughout Masaki Kobayashi’s relatively short career, his overriding concern was the place of the conscientious individual within a corrupt society. Perhaps most clearly seen in his magnum opus,

Throughout Masaki Kobayashi’s relatively short career, his overriding concern was the place of the conscientious individual within a corrupt society. Perhaps most clearly seen in his magnum opus,