Japan’s kaiju movies have an interesting relationship with their monstrous protagonists. Godzilla, while causing mass devastation and terror, can hardly be blamed for its actions. Humans polluted its world with all powerful nuclear weapons, woke it up, and then responded harshly to its attempts to complain. Godzilla is only ever Godzilla, acting naturally without malevolence, merely trying to live alongside destructive forces. No creature in the Toho canon embodies this theme better than Godzilla’s sometime foe, Mothra. Released in 1961, Mothra does not abandon the genre’s anti-nuclear stance, but steps away from it slightly to examine another great 20th century taboo – colonialism and the exploitation both of nature and of native peoples. Weighty themes aside, Mothra is also among the most family friendly of the Toho tokusatsu movies in its broadly comic approach starring well known comedian Frankie Sakai.

Japan’s kaiju movies have an interesting relationship with their monstrous protagonists. Godzilla, while causing mass devastation and terror, can hardly be blamed for its actions. Humans polluted its world with all powerful nuclear weapons, woke it up, and then responded harshly to its attempts to complain. Godzilla is only ever Godzilla, acting naturally without malevolence, merely trying to live alongside destructive forces. No creature in the Toho canon embodies this theme better than Godzilla’s sometime foe, Mothra. Released in 1961, Mothra does not abandon the genre’s anti-nuclear stance, but steps away from it slightly to examine another great 20th century taboo – colonialism and the exploitation both of nature and of native peoples. Weighty themes aside, Mothra is also among the most family friendly of the Toho tokusatsu movies in its broadly comic approach starring well known comedian Frankie Sakai.

When a naval vessel is caught up in a typhoon and wrecked, the crew is thought lost but against the odds a small number of survivors is discovered in a radiation heavy area previously thought to be uninhabited. The rescued men claim they owe their existence to a strange new species of mini-humans living deep in the forest. This is an awkward discovery because the islands had recently been used for testing nuclear weapons and have been ruled permanently uninhabitable. The government of the country which conducted the tests, Rolisica, orders an investigation and teams up with a group of Japanese scientists to verify the claims.

Of course, the original story of the survivors was already a media sensation and so intrepid “snapping turtle” reporter Zen (Frankie Sakai) and his photographer Michi (Kyoko Kagawa) are hot on the trail. Zen is something of an embarrassment to his bosses but manages to bamboozle his way into the scientific expedition by stowing away on their boat and then putting on one of their hazmat suits to blend in before anyone notices him. Linguist Chujo (Hiroshi Koizumi) gets himself into trouble but is saved by two little people of the island who communicate in an oddly choral language. Unfortunately, the Rolisicans, led by Captain Nelson (Jerry Ito), decide the helpful little creatures are useful “samples” and intend to kidnap them to experiment on. Refusing to give up despite the protestations of the Japanese contingent, Nelson only agrees to release the pair when the male islanders surround them and start banging drums in an intimidating manner.

The colonial narrative is clear as the Rolisicans never stop to consider the islanders as living creatures but only as an exploitable resource. Nelson heads back later and scoops up the two little ladies (committing colonial genocide in the process) but on his return to Japan his intentions are less scientific than financial as he immediately begins putting his new conquests on show. The island ladies (played by the twins from the popular group The Peanuts, Yumi and Emi Ito) are installed in a floating mini carriage and dropped on stage where they are forced to sing and dance for an appreciative audience in attendance to gorp.

Zen and Michi may be members of the problematic press who’ve dubbed the kidnapped islanders the “Tiny Beauties” and helped Nelson achieve his goals but they stand squarely behind the pair and, along with linguist Chujo and his little brother Shinji (Masamitsu Tayama), continue to work on a way to rescue the Tiny Beauties and send them home. The Tiny Beauties, however, aren’t particularly worried because they know “Mothra” is coming to save them, though they feel a bit sad for Japan and especially for the nice people like Zen, Michi, Chujo, and Shinji because Mothra doesn’t know right from wrong or have much thought process at all. 100% goal orientated, Mothra’s only concern is that two of its charges are in trouble and need rescuing. It will stop at nothing to retrieve them and bring them home no matter what obstacles may be standing in the way.

The island people worship Mothra like a god though with oddly Christian imagery of crosses and bells. Like many of Toho’s other “monsters” it is neither good or bad, in a sense, but simply exists as it is. Its purpose is to defend its people, which it does to the best of its ability. It has no desire to attack or destroy, but simply to protect and defend. The villain is humanity, or more precisely Rolisica whose colonial exploits have a dark and tyrannical quality as they try to insist the islands are uninhabited despite the evidence and then set about exploiting the resources with no thought to the islanders’ wellbeing. The Japanese are broadly the good guys who very much do not approve of the Rolisicans’ actions but they are also the people buying the tickets to see the Tiny Beauties and putting them on the front pages of the newspapers. Nevertheless, things can only conclude happily when people start respecting other nations on an equal footing and accepting the validity of their rights and beliefs even if they include giant marauding moth gods.

Original trailer (no subtitles)

The Peony Lantern (牡丹燈籠, Kaidan Botan Doro) has gone by many different names in its English version – The Bride from Hades, The Haunted Lantern, Ghost Beauty, and My Bride is a Ghost among various others, but whatever the title of the tale it remains one of the best known ghost stories of Japan. Originally inspired by a Chinese legend, the story was adapted and included in a popular Edo era collection of supernatural tales, Otogi Boko (Hand Puppets), removing much of the original Buddhist morality tale in the process. In the late 19th century, the Peony Lantern also became one of the earliest standard rakugo texts and was then collected and translated by Lafcadio Hearn though he drew his inspiration from a popular kabuki version. As is often the case, it is Hearn’s version which has become the most common.

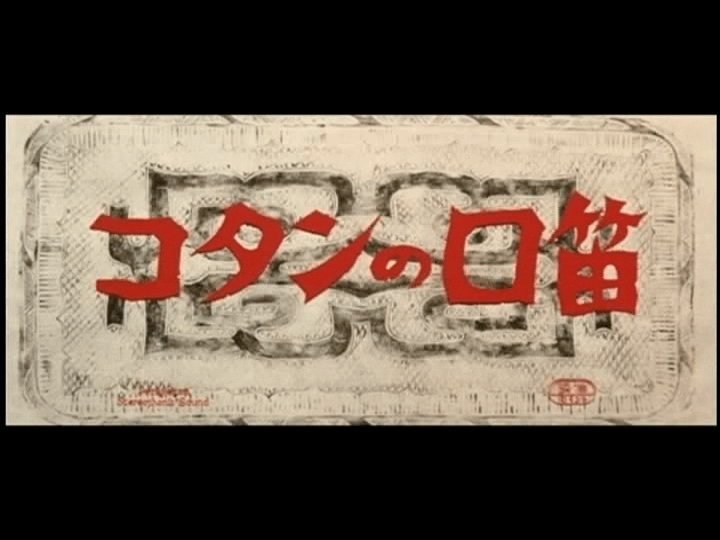

The Peony Lantern (牡丹燈籠, Kaidan Botan Doro) has gone by many different names in its English version – The Bride from Hades, The Haunted Lantern, Ghost Beauty, and My Bride is a Ghost among various others, but whatever the title of the tale it remains one of the best known ghost stories of Japan. Originally inspired by a Chinese legend, the story was adapted and included in a popular Edo era collection of supernatural tales, Otogi Boko (Hand Puppets), removing much of the original Buddhist morality tale in the process. In the late 19th century, the Peony Lantern also became one of the earliest standard rakugo texts and was then collected and translated by Lafcadio Hearn though he drew his inspiration from a popular kabuki version. As is often the case, it is Hearn’s version which has become the most common. The Ainu have not been a frequent feature of Japanese filmmaking though they have made sporadic appearances. Adapted from a novel by Nobuo Ishimori, Whistling in Kotan (コタンの口笛, Kotan no Kuchibue, AKA Whistle in My Heart) provides ample material for the generally bleak Naruse who manages to mine its melodramatic set up for all of its heartrending tragedy. Rather than his usual female focus, Naruse tells the story of two resilient Ainu siblings facing not only social discrimination and mistreatment but also a series of personal misfortunes.

The Ainu have not been a frequent feature of Japanese filmmaking though they have made sporadic appearances. Adapted from a novel by Nobuo Ishimori, Whistling in Kotan (コタンの口笛, Kotan no Kuchibue, AKA Whistle in My Heart) provides ample material for the generally bleak Naruse who manages to mine its melodramatic set up for all of its heartrending tragedy. Rather than his usual female focus, Naruse tells the story of two resilient Ainu siblings facing not only social discrimination and mistreatment but also a series of personal misfortunes. Kwaidan (怪談) is something of an anomaly in the career of the humanist director Masaki Kobayashi, best known for his wartime trilogy The Human Condition. Moving away from the naturalistic concerns that had formed the basis of his earlier career, Kwaidan takes a series of ghost stories collected by the foreigner Lafcadio Hearn and gives them a surreal, painterly approach that’s somewhere between theatre and folktale.

Kwaidan (怪談) is something of an anomaly in the career of the humanist director Masaki Kobayashi, best known for his wartime trilogy The Human Condition. Moving away from the naturalistic concerns that had formed the basis of his earlier career, Kwaidan takes a series of ghost stories collected by the foreigner Lafcadio Hearn and gives them a surreal, painterly approach that’s somewhere between theatre and folktale.